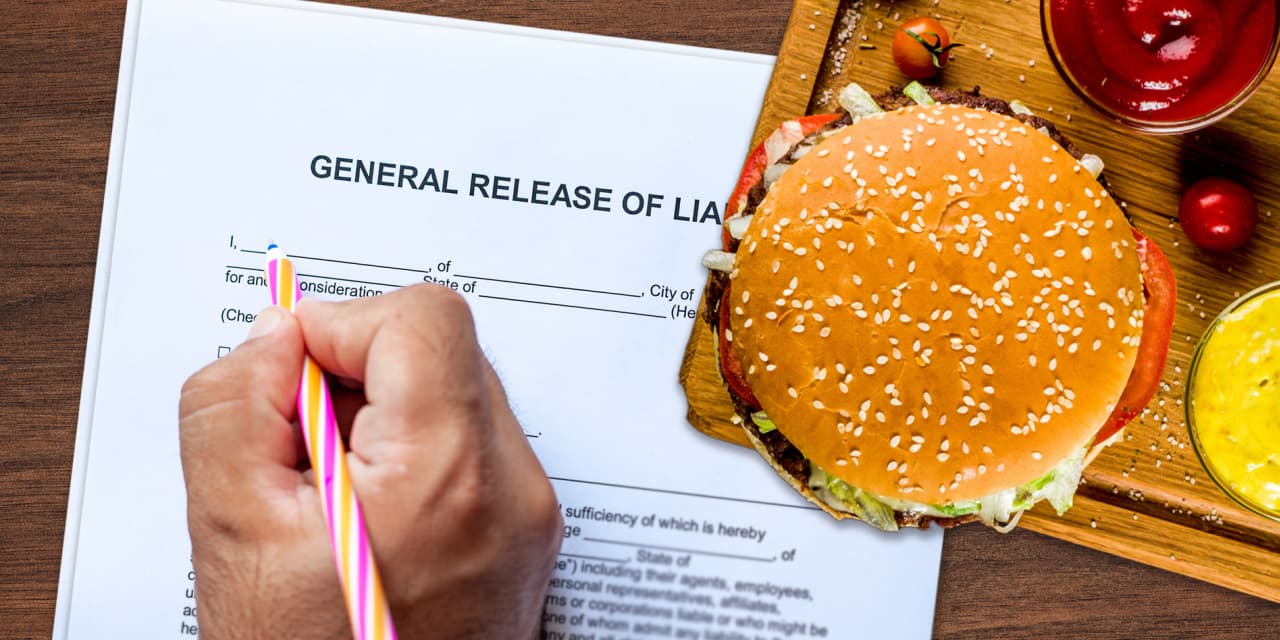

That’s the thought some might be having in light of the news a Toronto hotel asked a customer who ordered a burger cooked medium to sign a waiver relieving the establishment of any liability claims related to food-borne illnesses.

The customer recently shared the story on Reddit and it quickly went viral. On Reddit alone, the post has received more than 200 comments, with many expressing some strongly negative views about the situation.

“I don’t know why they feel the need to make everything well done,” said one. “Seems like a joke,” said another.

But this was no joke. As much as some of us like a juicy burger done to a medium or even rare turn, food-safety experts have long said the safest way to prepare the meat is to cook it fully. And in Ontario, the Canadian province where Toronto is located, there are guidelines in place that spell out the degree of burger doneness.

In a statement, a representative for Toronto’s public-health department said that “Food premises that use alternate cooking methods or processes (i.e., serve burgers cooked to different internal temperatures) are required to demonstrate how their processes ensure that the food is safe for consumption.”

All of which clearly set the stage for the waiver at the establishment in question, the Hilton

HLT,

Toronto Airport Hotel & Suites. A Hilton spokesperson said the waiver used language that was similar to warnings or advisories “you might see printed at the bottom of restaurant menus” concerning foods that carry risks.

The spokesperson added, “We are in the process of adding a disclaimer to our restaurant menus and will discontinue use of the waiver.”

In the U.S., warnings are indeed commonly seen on restaurant menus concerning raw or undercooked meat and seafood (think sushi), among other items. In fact, some state and local governments mandate the advisories. But waivers are far less typical, though some establishments have them in place. In most cases, those situations involve menu items that are super-spicy.

An example: Joella’s, a chicken chain with locations in four states, offers a Fire-in-da-Hole chicken dish, made with a mix of ghost and Carolina peppers, that promises an “immediate and intense burn upfront, with the flavors lingering, leaving a lasting impression.” And yes, a waiver is required for those who order the item, with the chain saying “spice enthusiasts and thrill-seekers” sign it “as a badge of honor.”

Brine, a chicken restaurant with locations in New York and New Jersey, just joined the so-fiery-it-necessitates-a-waiver bandwagon. Earlier this month, it introduced its DNE (as in Do Not Eat) sandwich, also made with a sauce that combines some intensely hot peppers.

Dan Mezzalingua, chief executive and founder of Brine, said the sandwich is “one of the hottest in the country” and the waiver is there to warn diners “this is not something to be taken lightly.” Plus, the waiver serves “to protect ourselves” from liability, he said.

But even Mezzalingua, who is married to a lawyer, acknowledges the waiver might not protect him fully should a patron decide to take legal action.

“There’s no such thing as ironclad,” Mezzalingua said.

Many attorneys and food experts amplify that point: A customer can always sue — and a business can be found at fault, waiver or no waiver. In short, an establishment must assume a basic level of responsibility for the welfare of its customers.

“The restaurant is the knowledgeable party and effectively warrants food safety,” said Mark Haas, chief executive with the Helmsman Group, a food-industry consultancy company.

Which leads many in the industry to suspect that when waivers are posted, they’re often as much a marketing gimmick — that is, a way for the restaurant to call attention to itself — as a form of legal protection.

“It’s like a stage effect,” said Steve Zagor, a veteran restaurant professional who lectures about the dining industry at Columbia University’s business school.

Restaurants do get sued for a variety of reasons, including selling food that makes people sick or otherwise harms them. Perhaps the most famous example is when McDonald’s lost a lawsuit involving a customer who was badly burned by its hot coffee. The fast-food chain didn’t have any kind of waiver in place, though it did have a warning about the coffee’s temperature. (McDonald’s didn’t respond to a MarketWatch request for comment.)

But in a country that can be as litigious as ours, the question remains if the waiver concept could be extended to a variety of menu items. Will your neighborhood sushi restaurant have you sign something before you devour your tuna roll? What about the local diner that serves that perfect medium-rare burger?

Restaurant-industry experts say it’s doubtful establishments in the U.S. will go too far for one simple reason: It may turn off customers and lead them to instead pick a dining establishment that doesn’t require a waiver.

Plus, such a waiver can generate a lot of negative reaction on social media and elsewhere, as certainly seemed to be the case with the Toronto Hilton hotel.

“The negative publicity far outweighs any potential of liability,” said Zagor.

Read the full article here