This is an article that builds on the content of the primer I wrote on the company five months ago here on Seeking Alpha. If you are interested, click here.

Some reflections on competitive advantages in commoditized businesses

Northeast Bank (NASDAQ:NBN) is a small regional US bank based in Portland, Maine. The bank was originally founded in 1872 and had an unremarkable history until 2010. In that year, a group of investors led by Rick Wayne acquired NBN and began to successfully implement a strategy of buying commercial real estate (CRE) loans in the secondary market at a discount. The rest is history, and since then the value creation for NBN shareholders has been great: the share price has multiplied by a factor of 5, not counting the (modest) amount paid out in dividends.

In my original article, I argued that the main reason for such an extraordinary track record was nothing more than the way in which the bank was structured. I posited that:

“NBN’s most important competitive advantage is underappreciated by the market. And that is the unconventional way in which the company is structured. Although legally a bank, it is run as a credit fund, but one with superior structural features to a traditional credit fund. First, NBN’s cost of funds is lower (although, remember, higher than that of well-established regional banks) than that of private equity funds: the latter have higher return expectations, allowing NBN to outbid them on many good performing loans. […] Finally, and most crucially, NBN access to capital is better, as they can flex up their balance sheet quite dramatically when the opportunity arises (NBN’s only constraint is equity capital). […] Conversely, when there are no opportunities to deploy capital intelligently, NBN allows its liabilities to run off, as they don’t have to be fully invested like most funds.”

Readers may be wondering why this feature is so important and whether it can actually be a source of a sustainable competitive advantage. After all, banking is generally a commoditized business where it is very difficult to find companies with durable competitive advantages unless they operate in a niche market.

It is important to recognize that the insurance business is more of the same, a business with low barriers to entry and where companies compete on price by offering essentially the same undifferentiated product. However, these permanent features of the industry have not prevented some companies from building excellent and highly profitable businesses with a long history of value creation.

How so? In general, the track record of value creation in these insurance companies stems from small and quirky features that arise either from corporate governance, the way these companies are organized, or a combination of both. In this spirit, Warren Buffett already clearly recognized the commoditized nature of the insurance business back in 1977, when he explained to shareholders that:

“Insurance companies offer standardized policies which can be copied by anyone. Their only products are promises. It is not difficult to be licensed, and the rates are an open book. There are no important advantages from trademarks, patents, location, corporate longevity, raw material sources, etc., and very little consumer differentiation to produce insulation from competition. It is commonplace, in corporate annual reports, to stress the difference the people make. Sometimes this is true and sometimes it isn’t. But there is no question that the nature of the insurance business magnifies the effect which individual managers have on company performance.” (W. Buffett, Letter to Shareholders 1977)

Two years later, in his 1979 Letter to Shareholders, he expanded on this topic, explaining that Berkshire’s insurance results were poised to be different from the industry’s because Berkshire simply did things differently:

“We hear about a great many insurance managers talk about being willing to reduce volume in order to underwrite profitably, but we find that very few actually do so. […] It is our policy not to lay off people because of the large fluctuations in work load produced by such voluntary volume changes. We would rather have some slack in the organization from time to time than keep everyone terribly busy writing business on which we are going to lose money.” (W. Buffett, Letter to Shareholders 1979)

And to drive the point home, seven years later, he forcefully explained why Berkshire’s way of running the insurance operation was simply superior to most of its peers, in a sentence that is basically pure timeless wisdom and perfectly illustrates the benefits of taking a long-term view:

“[W]e don’t engage in layoffs when we experience a cyclical slowdown at one of our generally-profitable insurance operations. This no-layoff practice is in our self-interest. Employees who fear that large layoffs will accompany sizable reductions in premium volume will understandably produce scads of business through thick and thin (mostly thin).” (W. Buffett, Letter to Shareholders 1986)

And while Berkshire is arguably the most successful insurer in history, it is by no means unique. In the insurance world alone, there are other examples of companies (e.g., Progressive, State Farm, Admiral in the UK) that have achieved phenomenal success in the past by making some minor tweaks to the “established” model of doing business. This list would go on and on if we included winners in other commoditized sectors (did anyone mention NVR?).

Andy Beal 2.0?

In my view, banking falls squarely into this category of business. In fact, the late Charlie Munger once said that “[i]nsurance is not that great a business. It’s a tough game. There are temptations to be stupid. It’s like banking.”

As many readers will know, Munger was also a strong advocate of a latticework of mental models to help us make investment decisions. Since Berkshire is one of the right templates for thinking about insurance companies in general, the question is then: are there any good mental models in banking that could help us frame the discussion about NBN’s peculiar business model?

I think one of the most instructive examples in banking, and one that is very relevant to us, is the story of Andy Beal. For those who have never heard of him, Beal, born in Lansing (Michigan) in 1952, is currently the wealthiest banker in America, with a net worth of around $10bn. That amount is impressive in itself, but what is most fascinating is that he built it up from scratch and in an unconventional way. After a few property deals in his early adulthood, Beal founded Beal Bank (Texas) in 1988 and Beal Bank USA (Las Vegas) in 2004. For those interested in the intricacies of the character, Forbes did a great (and rare) profile of Beal’s career back in 2009, provocatively titled “The Banker Who Said No”(here).

A key feature of both banks’ operations has been the decisiveness and boldness of Beal’s bets over time. He bought power generation and infrastructure bonds during the energy deregulation crisis of 2001, aircraft-backed debt instruments after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, commercial and real estate loans during the global credit crisis of 2008, energy bonds after the shale crash in the mid-2010s and, most recently, massive amounts of TIPS with maturities of up to three years, betting on a spike in inflation.

However, the previous pattern would not have been possible without the unconventional way in which both banks’ balance sheets worked. Unlike virtually all of their peers, the balance sheets worked like an “accordion”, inflating when opportunities arose (for a given amount of capital, the liability side of the balance sheet was expanded by issuing certificates of deposit) and shrinking it when there was nothing intelligent to do.

This way of running a bank is quite unconventional in several ways. First and foremost, there is little emphasis on the institution’s “deposit franchise”, as it is more important to be nimble than to have cheap funding (the net interest margin is supported not by cheap funding but by well-timed and high-yielding purchases). Another important implication of de-emphasizing the deposit franchise is that it avoids the need to have fixed costs tied to the local branches, and therefore the need to “always do something” in order to cover those costs. Secondly, having the flexibility to wait for the right opportunity allows you to be more selective and to operate in your circle of competence. Finally, because you are essentially operating in the secondary market (i.e., buying loans with a credit history), you usually have a better sense of the quality of the underlying asset than the original underwriter and you are not forced to sell if conditions are not good.

As you can see, as in the case of Berkshire, none of this is rocket science, but executing the strategy over the long term is difficult because it requires conviction, the right kind of temperament and a proper incentive structure. The following excerpt from the Forbes article perfectly exemplifies the peer pressure involved in executing the strategy:

“For three long years, from 2004 to 2007, he virtually stopped making or buying loans. While the credit markets were roaring and lenders were raking in billions, Beal shrank his bank’s assets because he thought the loans were going to blow up. He cut his staff in half and killed time playing backgammon or racing cars. He took long lunches with friends, carping to them about “stupid loans.” His odd behavior puzzled regulators, credit agencies and even his own board. They wondered why he was seemingly shutting the bank down, resisting the huge profits the nation’s big banks were making. One director asked him: “Are we a dinosaur?”.”

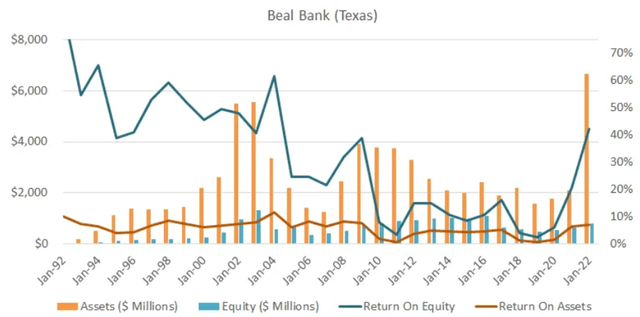

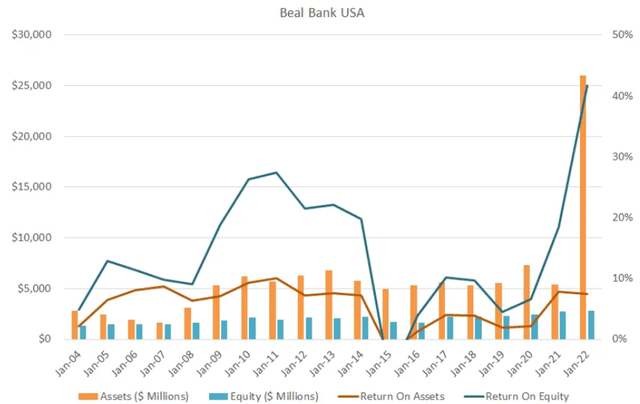

Beal’s track record is shown in the following two charts, courtesy of Frederik Gieschen. Each graph depicts the evolution of assets, equity, and profitability (ROA and ROE) for each bank over time:

The Alchemy of Money Substack, 2023, High Roller: Lessons from America’s Richest Banker. The Alchemy of Money Substack, 2023, High Roller: Lessons from America’s Richest Banker.

The performance of both banks clearly shows that this has been a winning business model over a long period of time. Although volatile, the return on assets and return on equity have been simply exceptional, with ROEs averaging over 20% (higher in the case of Beal Bank Texas) over several decades. The evolution of leverage, as explained above, has shown wild swings: for instance, looking at Beal Bank USA, shortly after its inception, the bank’s assets were fully funded by equity, but within a few years (2009-’10) the balance sheet was leveraged to look more like a traditional bank. More recently, in a similar fashion, the leverage has exploded to take advantage of post-pandemic opportunities.

Some comments on 1Q’24 results and brief thoughts on valuation

With this framework in mind, let’s review NBN’s recent results. Although there are some notable differences between NBN and Beal’s banks (most importantly NBN’s scope is narrower, as it has only historically dealt with CRE loans, whereas Beal has participated in many sectors), I believe the similarities are striking.

It is worth stressing that having a Beal-like framework does not guarantee immediate success, but it does help to understand what Rick Wayne and his team are trying to accomplish here. As I explained in my original article, Rick (as he prefers to be called rather than Mr. Wayne) has shown himself to be a shrewd capital allocator and not afraid to make big bets (like Beal) when the opportunity is right. Rick and his team could have easily deployed capital much earlier, thus boosting short-term growth, but instead they waited for more than a decade.

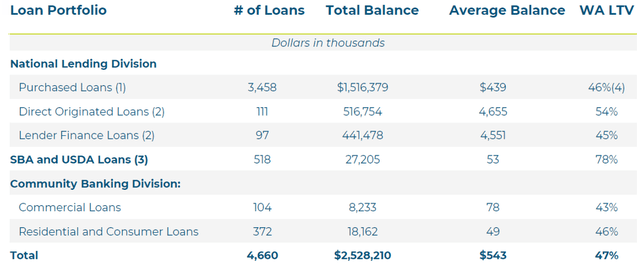

NBN’s 1Q’24 results were extremely strong, with loan volumes of $130M ($52.4M purchased and $68M originated), a net interest margin of 5.3%, minimal credit losses and an overall ROA of 2.1% and an ROE of 19.8%. Every quarter that passes strengthens the bank’s credit prospects for two reasons: firstly, equity grows in line with the ROE (so there is more capital to deploy down the line) and secondly, loans are being paid and have more equity protection underneath them. From a qualitative perspective, Rick sounded quite optimistic on the call about the ability to originate more loans at attractive terms over the next few quarters.

The following table summarizes the main metrics of the loan portfolio, which were little changed from the previous quarter:

Northeast Bank, 1Q’24 Results Presentation.

I am not going to say much about valuation, since I think it is relatively easy to get a range of outcomes without any fancy mathematical models. The question boils down to: how much would you pay for an extremely well-run bank trading slightly above book value? If you believe that future ROEs will be in the range of 15-20%, then that will be the IRR of the investment over a long period of time. Period. Of course, this does not take into account any multiple expansion that may occur in the future, but that is not necessary for the thesis to work satisfactorily. Given the turbulent macro environment, I have no doubt that Rick and his team will be able to create additional shareholder value, either in the form of loan acquisitions or, if the price is right, in the form of share buybacks.

Grab some popcorn for the next few years and watch a real business case study (mental model?) in action.

Editor’s Note: This article was submitted as part of Seeking Alpha’s Top 2024 Long/Short competition, which runs through December 31. With cash prizes, this competition — open to all contributors — is one you don’t want to miss. If you are interested in becoming a contributor and taking part in the competition, click here to find out more and submit your article today!

Read the full article here