Frontline (NYSE:FRO) (up 89% year-to-date) has vastly outperformed the S&P and is still my top long position going into 2024.

The tanker market has been supported by a significant figure of oil in transit or barrels at sea since the end of 2021. As the buildup in land oil inventories after the 2020 Covid-19 global recession was worked through, the tanker sector experienced a slight hangover from the storage and oil transportation bonanza. As refineries worked off stocks, there was little need for seaborne oil transportation. As oil in transit has recovered so have tanker equities with many names up triple digits, yet there is still a lot of room for the tanker space to continue appreciating in my view.

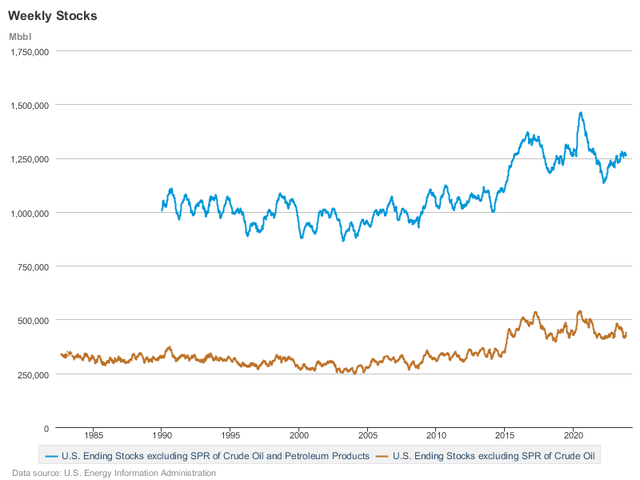

Oil in transit (Lars Barstad, CEO Frontline) EIA oil inventories (EIA)

Oil tanker rates and profits are highly affected by oil markets though oil prices and tanker rates are not correlated. I will convey in this article why lower oil prices are more bullish for tanker companies than higher oil prices. The reason is simply that rising oil inventories are negatively correlated with oil prices as greater supply or inventories weigh on oil prices. Inventory rises almost always require an increase in oil in transit and tanker demand.

OPEC has been clinging to keep the WTI futures curve in backwardation and defending the front end of the curve also known as short-dated futures prices. This is because when the oil futures curve slopes downwards, traders and purchasers such as refineries cannot hedge by locking into a higher final realized sales price in the future. In essence, oil loses value with time. It also introduces an element of uncertainty into purchasing oil in the sense that selling-price risk cannot be mitigated appropriately through hedges unless one wishes to lock into a lower realized future sales price than the current market price of oil.

The opposite of backwardation is a contango or an upward-sloping futures curve. An example of a contango trade or hedge is simply buying a short-dated future and selling the higher-priced longer-dated future. A profit is locked in as long as the oil is held or stored. This allows buyers of oil to restock and know the oil won’t lose massive value with time if prices were to fall significantly. This incentivizes restocking and transportation of oil.

Why does OPEC want to keep the curve in backwardation? There are multiple reasons, though the main one is it eliminates the ability to hedge not only for the inventory restocking reason described above but also for non-OPEC production such as US shale. Non-OPEC producers will be resistant to hedging if oil futures prices slope downward. OPEC doesn’t hedge production.

The Middle East has the lowest production costs in the world and OPEC uses size and supply coordination rather than hedging. OPEC considers shale a threat to its market share. When futures prices in six months to a year are lower than current prices, it incentivizes shale to not hedge by not locking into a price that is lower than the current market price such as when the curve is in backwardation.

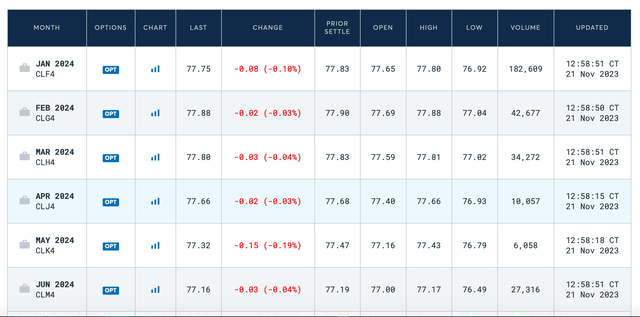

WTI Futures Quotes (CME Group)

As one can see in the image above, 1-month minus 3-month spreads are in contango, while 1-month minus 6-month spreads are still in backwardation. The shift from extreme backwardation into the early signs of contango was abrupt and coincided with rising US oil inventories at storage hubs such as Cushing, Oklahoma. Large algorithmic traders also use the “spreads of spreads” or the second derivative of time spreads to generate giant buy or sell orders and this has played a role in the backwardation narrowing much to the disdain of OPEC and Saudi Arabia.

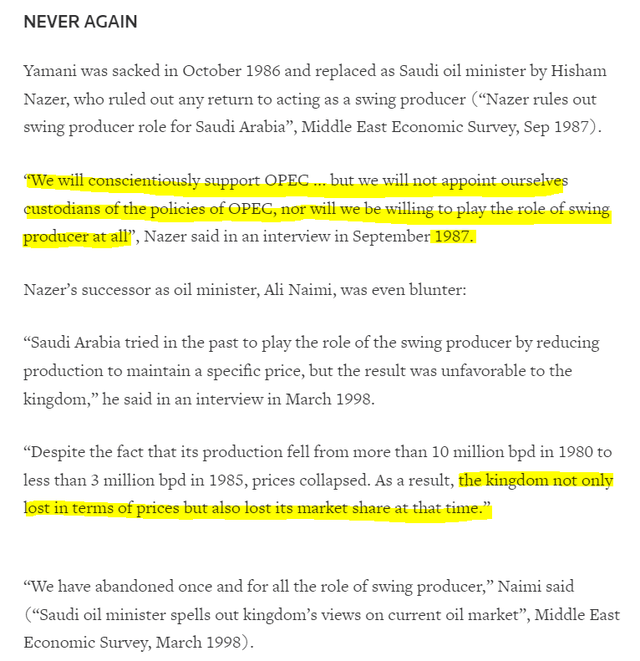

On to Saudi Arabia, one of my main ideas in the bearish oil thesis is Saudi Arabia cannot shoulder cuts for the collective group any longer. At some point, the pain of lost production on the economy and government revenues as well as loss in global market share outweighs the benefits of maintaining the high-priced backwardation environment.

This is especially true because other nations such as Iraq are pumping above their allotted quota and have 400,00bpd capacity offline due to a disagreement with Turkey. The UAE quota will be increased in January 2024 and even non-OPEC nations such as Venezuela are allowed to increase production due to the easing of US sanctions. Saudi Arabia and Russia cannot be expected to subsidize OPEC’s overproduction and the world’s waning oil demand indefinitely. Russia may have more defiance about deeper cuts and is less committed to OPEC cohesion than Saudi Arabia, in my opinion. The most recent OPEC meeting has been delayed due to production quota disagreement amongst members.

Saudi Arabia Oil Minister Historical Quotes (AyusoValue, Twitter)

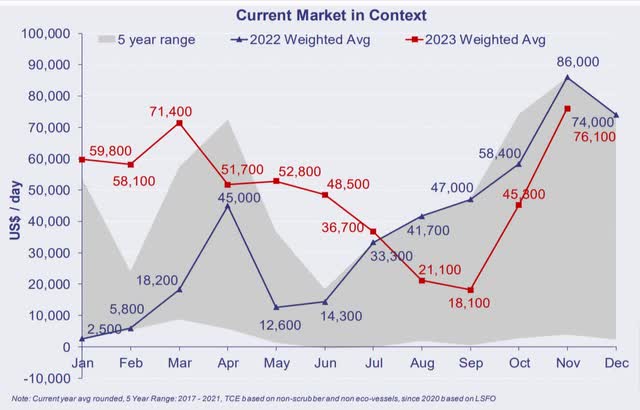

Tanker rates are notoriously volatile and respond quickly to market changes and sentiment as shown below. After hitting a low in 2021 with VLCC rates (second image) below operating costs for tanker owners (around $20K per day) tanker rates rose through the second half of 2022 into 2023. The most recent pullback ran from June through September on OPEC+’s latest production cut and this again reinforces my view that lower oil prices are bullish for tanker rates, profits, and share prices.

VLCC rates have been a bit more sluggish than Suezmax’s which is a smaller vessel size. Frontline is the largest publicly traded tanker company in the United States and has a diverse fleet of VLCC (very large crude carrier), Suezmax, and Afra/LR2 ships. DHT Holdings (DHT) is a pure play VLCC tanker stock which I am also long. Frontline’s exposure to LR2 and Suezmax shipping segments (which have outperformed VLCC rates) bodes well for Q3 earnings which are reported on November 30, 2023.

Suezmax Tanker Rates (Ed Finley-Richardson, Twitter) VLCC Tanker Rates (Ed Finley-Richardson, Twitter)

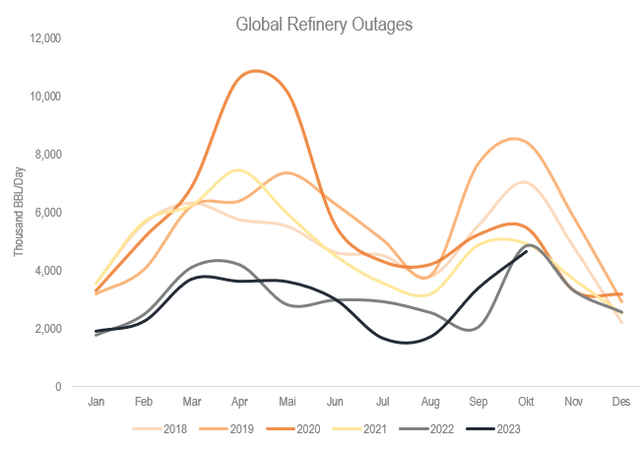

As we have entered Q4, tanker rates have picked back up after the summer doldrums and negative sentiment regarding lower OPEC production and exports has faded back into optimism for the sector. There is a lot of seasonality in the tanker sector and Q4 is typically a quarter for outperformance. This is due to the refinery maintenance cycle shown below courtesy of Frontline CEO, Lars Barstad via Twitter. As refineries kick back on, so should demand for oil transportation.

Refinery Outages (Lars Barstad CEO Frontline, Twitter)

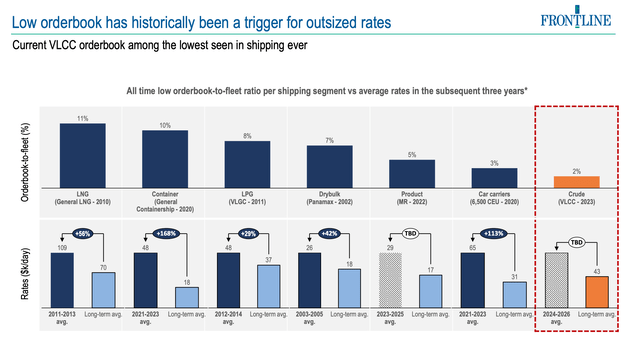

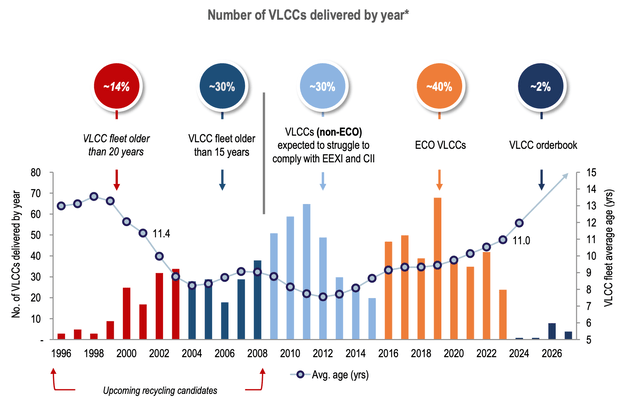

In short, currently, the global tanker fleet is old or struggling to comply with new environmental standards and thus many are primed for scrapping, while the shipyards are filled in LNG and containerships and there are a record low number of VLCC ships ordered to be built as a percent of the global fleet.

Outsized rates / Orderbook (Frontline) order book / vessel ages (Frontline)

Another point I want to cover is the geopolitics of oil shipping and the tanker sector. This is very important because it often affects global trade routes which are reflected in ton-mile demand for tankers. For example, when the Russian-Ukraine war began, Europe started importing more oil from the United States while Russian oil was sent to India and China. This has resulted in longer routes for ships and has been a profitable tailwind to tanker earnings.

Another example is Saudi Arabia’s voluntary production cuts. If Saudi Arabia chooses to endure the pain of production cuts, it should have a minimal effect on tankers, as Asian market share will just be picked up by North and South American producers shipping oil along a longer route.

Although unfortunate, Hamas and Israel’s conflict and general unrest in the Middle East is a potential reason for the tanker sector to outperform especially if Egypt and the Suez Canal or the Strait of Hormuz become involved in any way.

Next, I will cover the “shadow fleet” and the strategic importance of oil tankers in the shifting modern geopolitical landscape.

As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United States and Western allies decided to limit Russia’s oil revenue without a full embargo through a price cap system. If the West decided on a full embargo of Russian oil, oil prices could spike and increase Russia’s oil revenue, so instead, the United States said we would accept the supply but not at full cost. It’s very much a limiting mechanism. I would have endorsed a lower price cap though that is beside the point.

The way the price cap is enforced is through tanker and seaborne oil transportation insurance. Any ship carrying Russian oil above the price cap cannot register with global shipping and insurance agencies and institutions. This has created a shadow fleet of illegal and environmentally non-compliant, old tankers that would have been scrapped years ago.

Most of the illegal tonnage is shipping Iranian and Russian oil to China and India. This gives me confidence in the sector for two reasons. The first is that the United States is enforcing the price cap and is really laying down the law on any tanker owners shipping sanctioned oil.

In October, the United States imposed its first sanction on a tanker shipping Russian oil above the price cap and the vessel was forced to return to the United States. Recently, more enforcement actions have taken place. According to the Associated Press:

Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control imposed sanctions on three United Arab Emirates-based firms and blocked three ships that used U.S. service providers to carry Russian crude oil above the $60 price cap.

The sanctions block access to U.S. property and bank accounts and prevent the targeted people and companies from doing business with Americans. The actions on the ships blacklist them from transporting goods with U.S. service providers.

In a Bloomberg report, the United States also sent notices to ship management companies suspecting over 100 vessels shipping Russian oil above the cap. As the US continues to crack down on the shadow fleet, non-compliant and old vessel supply will come off the market while compliant, legal tankers will likely see increased demand.

The second reason the shadow fleet gives me confidence in the tanker sector is it insulates the compliant fleet from a potential slowdown in Chinese oil demand. China has greatly utilized the shadow fleet. The Chinese economy has slowed as I expected, though oil demand has remained resilient. If the slowdown eventually does take a toll on oil demand, it should have a minimal effect on the regulated tanker market because legal tankers were not being greatly utilized by Chinese oil importers anyway.

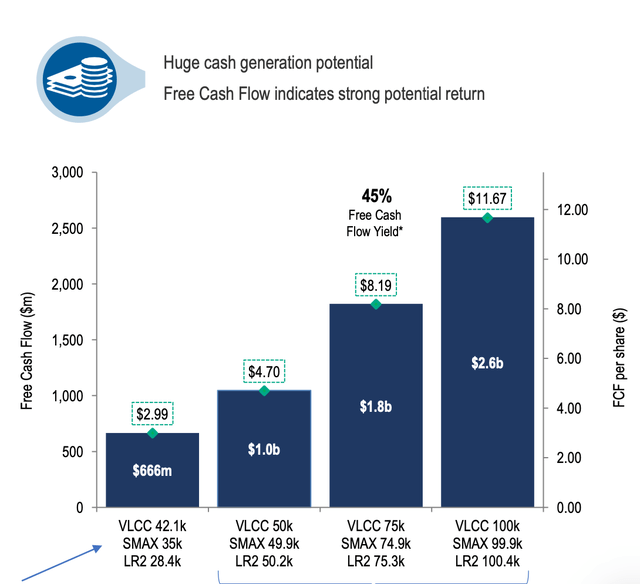

Lastly, I will cover valuation if the current tanker market dynamics persist, that is, assuming no upturn or downturn in oil transportation rates. Frontline is generating substantial profits currently relative to the company’s market capitalization and has a very high 12% dividend yield.

Frontline trades at only five times Q2 2023 earnings annualized, compared to the S&P which trades around twenty-five times earnings. As shown below in the second column (current VLCC, Suezmax, and LR2 rates), Frontline has sufficient operating leverage to generate approximately $1 billion in free cash flow annually. That is very significant for a company with a market cap of only $4.9 billion. I have a price target on Frontline of $40 per share as I think a double-digit dividend yield and a P/E ratio of only five is unsustainable. Either the share price appreciates or earnings and dividends fall. I lean towards the former. $40 a share would be an approximate ten times multiple on free cash flow given the current market.

Frontline Operating Leverage (Frontline)

In conclusion, I have been and continue to be long the tanker sector. I believe the extent of current profits has yet to be reflected in tanker securities prices and this is assuming no future upturn. If the tanker market does in fact get stronger, the upside is very high given the historical volatility in share prices and tanker rates. The risk-reward of the investment is very asymmetric in this light. Oil tankers, specifically Frontline, present a unique opportunity and versatile, strategic investment idea.

Editor’s Note: This article was submitted as part of Seeking Alpha’s Top 2024 Long/Short Pick investment competition, which runs through December 31. With cash prizes, this competition — open to all contributors — is one you don’t want to miss. If you are interested in becoming a contributor and taking part in the competition, click here to find out more and submit your article today!

Read the full article here