Federal Reserve’s Powell Signals Caution Amidst Rising Treasury Yields

The 30-year US Treasury bond yield recently surpassed 5%, hitting a 20-year high.

Investing.com

Last week, Fed Chair Powell commented that further rate hikes may not be needed if Treasury yields rise enough to tighten financial conditions. This signals the Fed is watching bond market moves closely to gauge their impact.

“Powell committed to “proceeding carefully,” signaling no rush to hike again. In the discussion that followed his opening remarks, Powell discussed the unexpected degree of economic strength. “It may just be that rates haven’t been high enough for long enough.” Source.

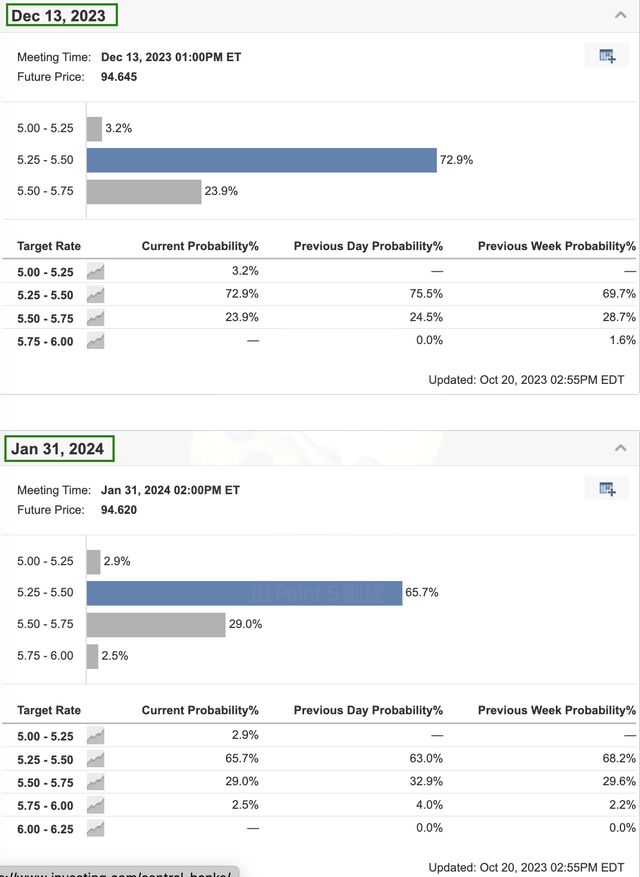

Market probability trackers show investors easing rate hike expectations in December 2023 and January 2024 post-Powell’s remarks. The market appears reassured that bond yields climbing may substitute for some of the Fed’s policy tightening.

Investing.com

Evaluating the Risk-Reward of Treasuries: Inflation and Geopolitical Factors

For investors, the key question now is whether Treasuries like iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (NASDAQ:TLT), down 18% year-to-date, is becoming a safer investment again.

To evaluate the risk-reward of TLT, we will analyze the two biggest drivers of Fed policy –

(1) Inflation and

(2) Regional conflicts

Assessing the Impact of Inflation on Bond Yields

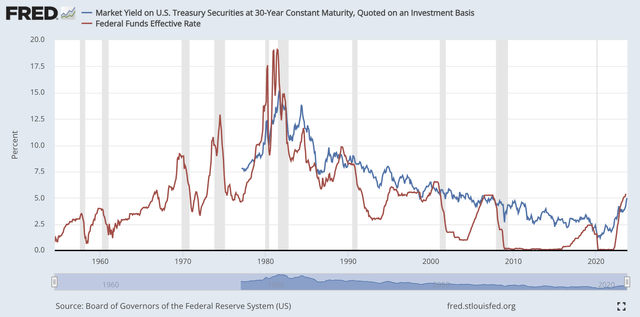

First, the chart below clearly shows the Fed funds rate (red line) is more volatile and drives the direction of the 30-year Treasury yield (blue line).

30-year treasury yield and Fed fund rate (FRED)

When the Fed cut rates to zero during the pandemic, the 30-year yield fell in tandem. As the Fed has hiked aggressively, longer yields have followed higher. This close relationship demonstrates Fed policy is the primary determinant of long-term yields.

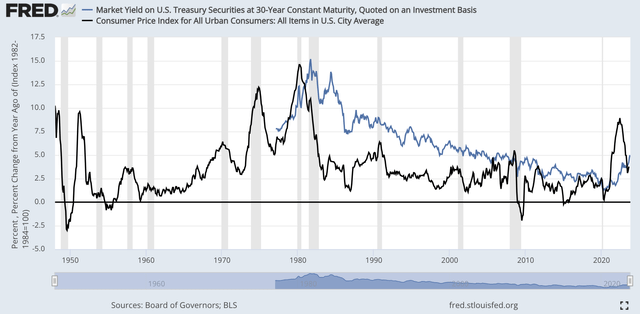

30-year treasury yield and Inflation (Fred)

Inflation indirectly impacts bond yields by influencing Fed decision-making. When inflation rose faster than expected earlier this year, it prompted more aggressive Fed tightening.

The Persistence of Sticky Services Inflation in Shelter and Transportation

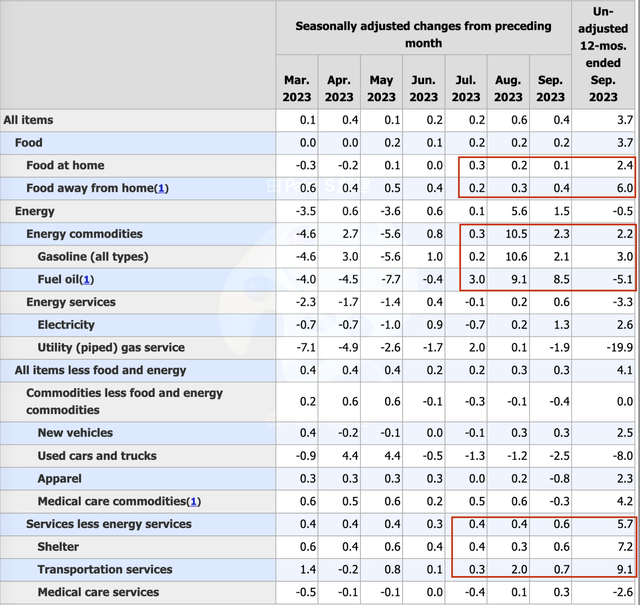

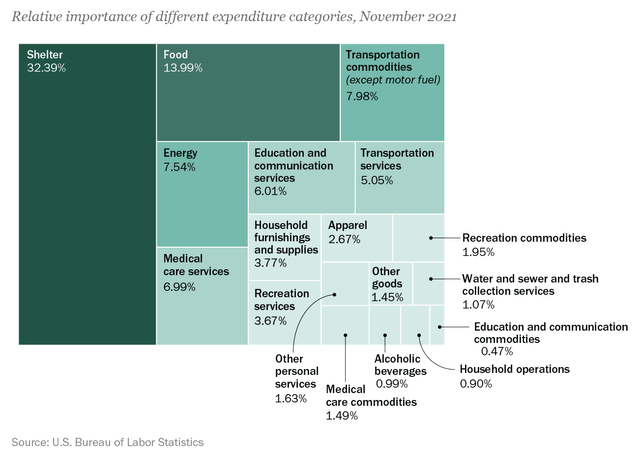

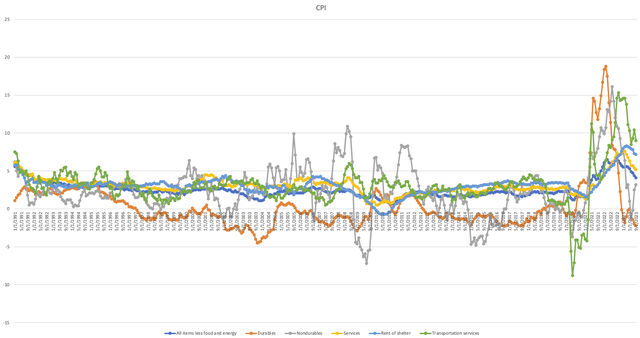

Digging into the inflation data, the main stubborn categories left are energy, food away from home, and services like shelter and transportation.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics

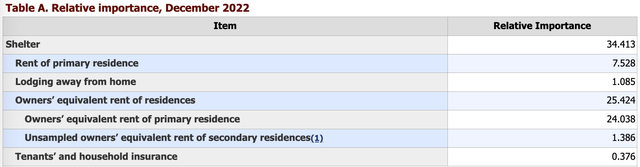

Notably, shelter and transportation services account for the largest CPI weightings at 32% and 8% respectively. Within shelters, owners’ equivalent rent (“OER”) and actual rents make up the bulk of the category.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics

US Bureau of Labor Statistics

OER essentially measures how much it would cost a homeowner to rent their owned property. It captures components like prices, property taxes, insurance, and maintenance.

Rents are still rising in inflation reports partly because rent contracts are typically negotiated on 12-month terms. So the CPI calculation includes a mix of existing lease rates and new higher prices.

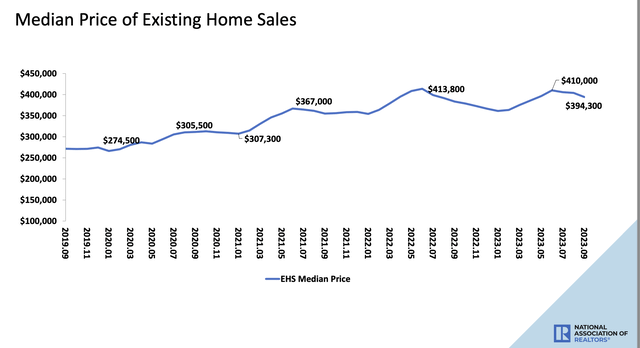

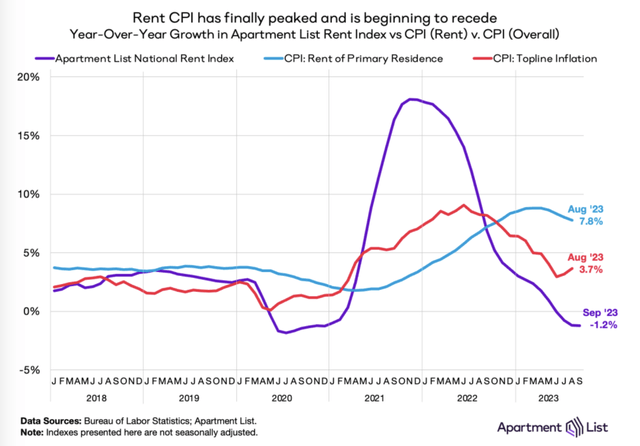

However, the charts below suggest both US house prices and rent growth are now decelerating. Rent growth is slowing faster than purchase prices because the supply of houses available for sale keeps decreasing, while the supply of rentals is growing.

Existing Home Sales (National Association of Realtors)

Rent price, CPI (Apartment List)

Balancing Affordability and Inflation in the Fed’s Interest Rate Policy

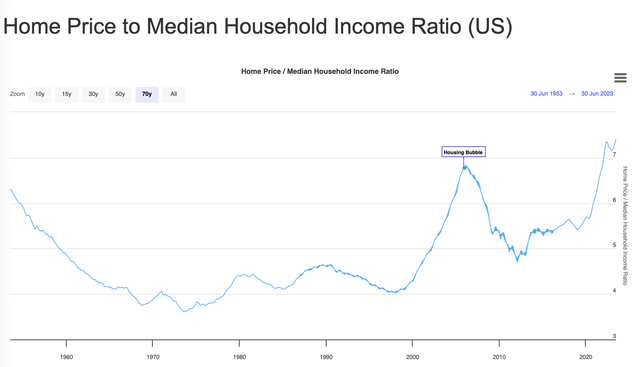

Nevertheless, over the past 50 years, the ratio of home prices to median household income has reached an all-time high. This raises questions for investors about what could potentially prevent the Fed from reducing interest rates next year. Even though housing prices are growing at a slower pace, affordability remains a significant concern.

Home price to income ratio (Longtermtrends)

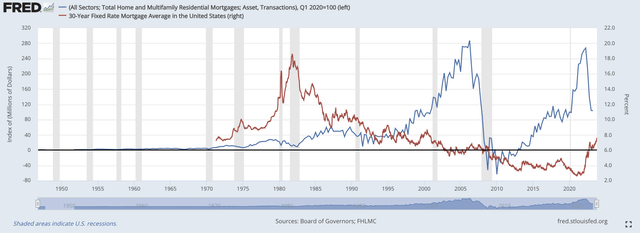

Further, even if the record mortgage rate has caused a significant decline in mortgage demand, it appears that we are still at a very high level of demand when compared to historical levels. This suggests that if home prices do not decrease as rapidly as expected, the Federal Reserve does not appear to be concerned about the declining housing demand resulting from higher mortgage rates.

Mortgage demand and Mortgage rate (FRED)

The question at hand is whether the deceleration trend in CPI, alongside elevated prices for durable goods like housing and cars, warrants the Federal Reserve to consider lowering interest rates next year, or if 2024 marks the beginning of a more sustained period of higher rates.

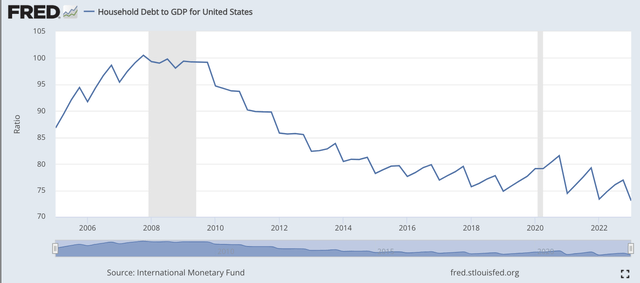

Based on historical experience, the Fed has tended to prioritize regulating inflation over considering affordability issues for households. Another way to address the affordability issue is by having households with lower interest rates have more debt on their balance sheets. This also explains why the long-term Treasury yield is constantly declining since adding more debt is the only option to address the debt issue.

The US household debt to GDP ratio is at an all-time low. This therefore supports the Fed’s decision to cut interest rates in 2024 once the CPI reaches its goal.

Household Debt to GDP (FRED)

The Role of Insurance Costs in Maintaining Inflation

Despite recent drops in home prices and rents due to slowing demand, OER continues pushing higher. One of the major driving forces is the rising insurance costs.

CPI (US Bureau of Labor Statistics)

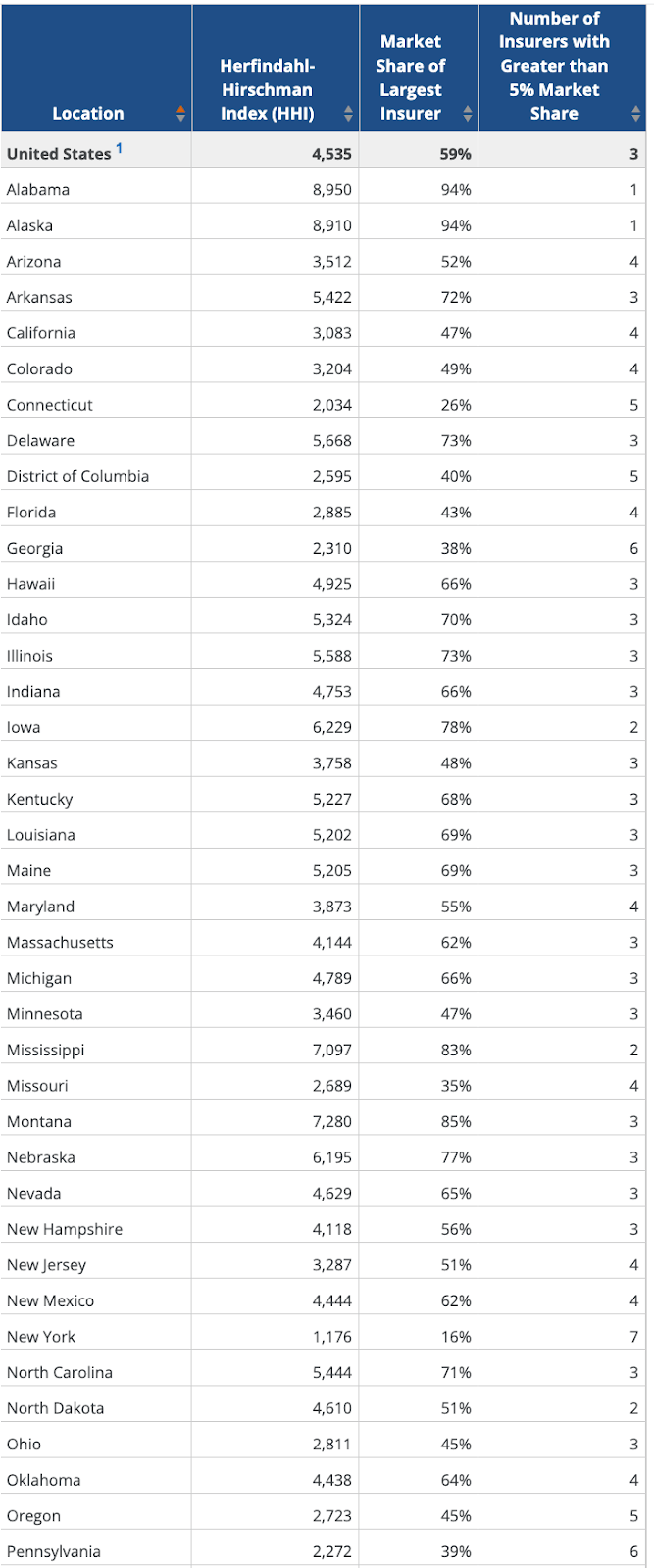

Insurance appears to be particularly sticky for some reasons. The insurance industry is highly concentrated, with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index consistent with high concentration levels. This grants insulation from competition to aggressively raise prices.

With insurers holding monopoly power in a constrained market, they can perpetuate inflation through periodic rate hikes. Many of them do so by monopoly in a single region/state as illustrated by KFF data.

KFF

Although regulated by the government, insurers can still obtain approval for large increases by citing higher costs. For example, Lemonade recently secured approval for 30% home and 23% pet insurance increases. Insurers are maximizing increases allowable under caps by pointing to inflation, climate change, and other cost pressures.

This poses a serious drag on consumer spending power since wage growth trails insurance inflation badly. In September 2023, for instance, auto insurance continued to grow at a very high rate—by 11%.

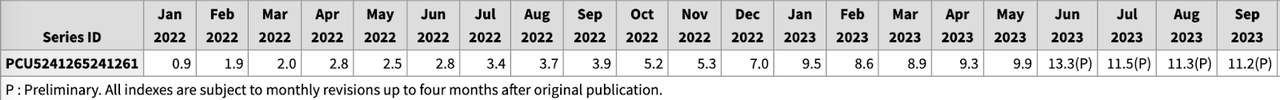

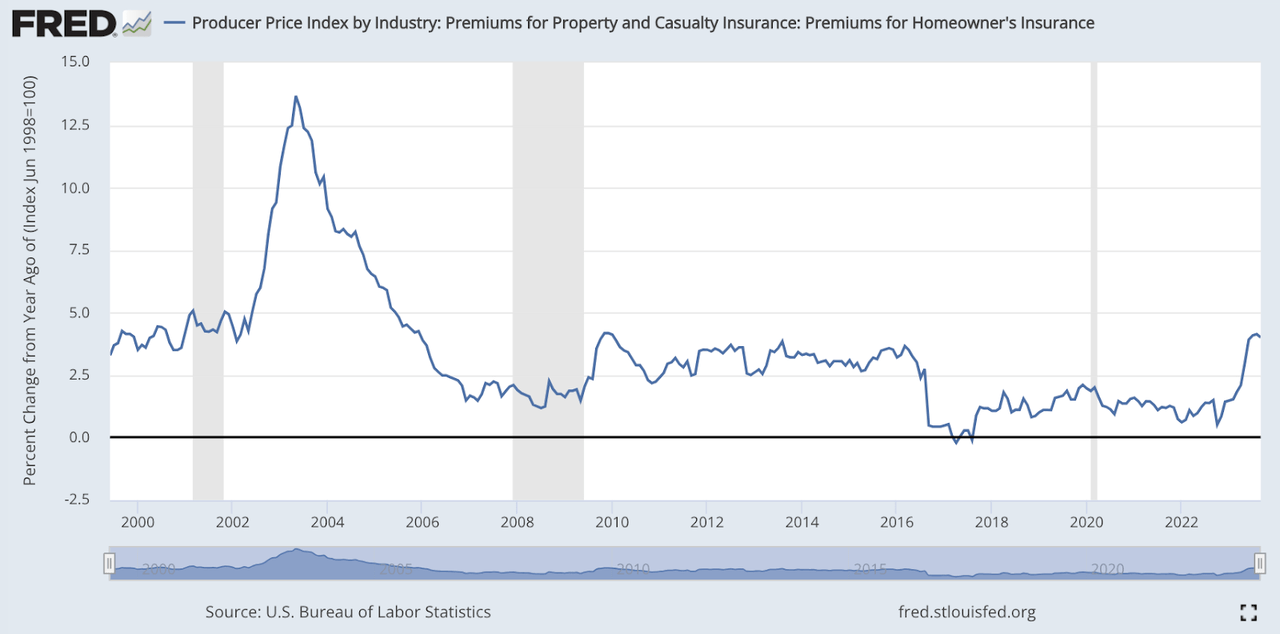

Auto Insurance premium growth (FRED)

Therefore, until service components like shelter and transportation move down materially, the Fed seems unlikely to pivot on rates. Services inflation remaining sticky and elevated prevents the clear disinflation the Fed needs to see. Besides the housing prices, any durable decline in insurance costs would be a signal potentially capping yields.

Home insurance premium growth (FRED)

Geopolitical Risks and Their Potential Impact on Bond Yields

A second factor for Fed policy is geopolitical risk. With US forces ready to engage militias in Syria and tensions escalating with Iran, investors are weighing the potential fallout.

Three scenarios warrant consideration: one where the United States becomes involved in a war, another where the United States refrains from engaging in war but faces an oil crisis, and a third where the United States avoids both war and an oil crisis.

The Scenarios of War and Oil Crisis

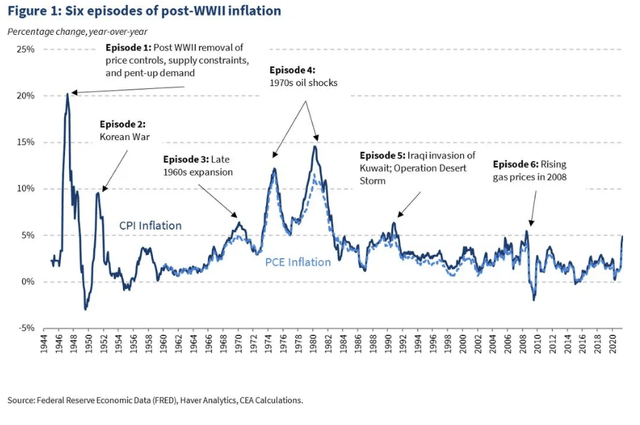

Conventional wisdom suggests war raises Treasury demand as a safe haven asset, lowering yields. But reviewing past wars shows inflation has instead often spiked.

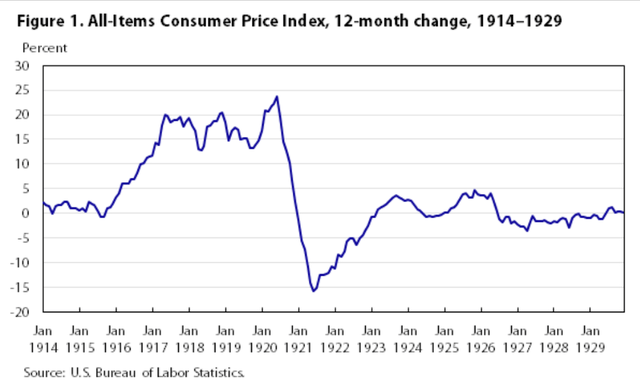

During World Wars I and II along with the Korean War, inflation frequently hit 15-20% as massive war spending strained resources.

CPI (FED)

CPI (FED)

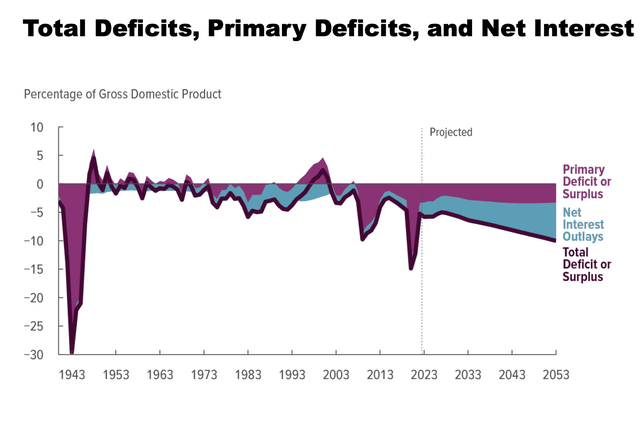

The chart below illustrates how the US budget deficit ballooned to -30% of GDP during World War II, fueling widespread inflation.

White house

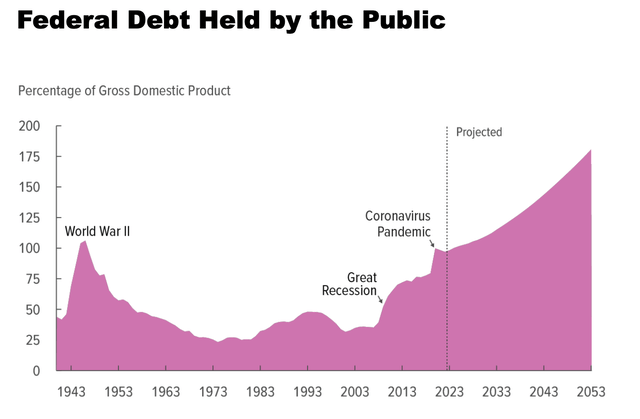

Today’s deficit projections already show a widening trend even without a new war, reaching an estimated -10% of GDP by 2053. Many investors such as Warren Buffet and Ray Dalio worry this debt trajectory is unsustainable. By 2053, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the debt-to-GDP ratio could exceed 180%, well above the World War II peak of 100%.

White house

With structural deficits stretching budgets even absent conflict, a new major war could be financially disastrous. This deterioration of US credit quality would normally pressure Treasury yields higher.

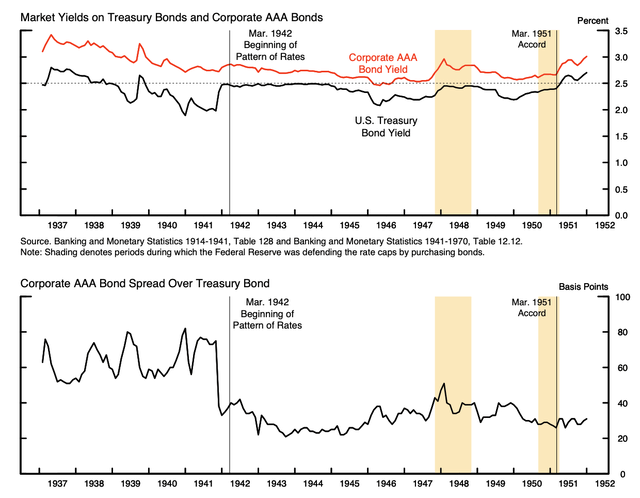

However, as a matter of fact, during past wars like World War II, the Fed has intervened by essentially suppressing yields through Treasury purchases to fund government spending needs. So despite high inflation eroding real returns, nominal yields have often fallen or remained low due to Fed intervention.

Banking and monetary statistics

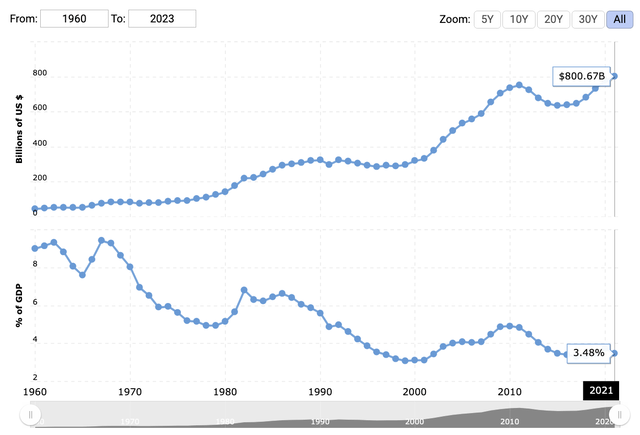

While we may not be experts in matters of war, if we simply assess the added capacity of the US government to respond to a conflict, the situation today may not be as dire as it appeared in 1970. US defense budget as a share of GDP is falling, reaching a record low of 3.5%, while overall spending is rising, reaching a record high of 800 billion in 2021. This implies that the US government can raise its defense spending if necessary.

US defense budget, budget as percentage of GDP in 1960-2021 (MACROTREND)

While large wars would logically pressure inflation higher, historical precedent shows the Fed has resisted this by maintaining artificially low rates. Therefore, the ideal scenario for bond investors could be if the US is at war and the Fed starts purchasing bonds once more.

The US: Not at War and Without Oil Crisis

This is the most probable scenario as the Fed remains sidelined for now, keeping rates elevated until inflation moderates further.

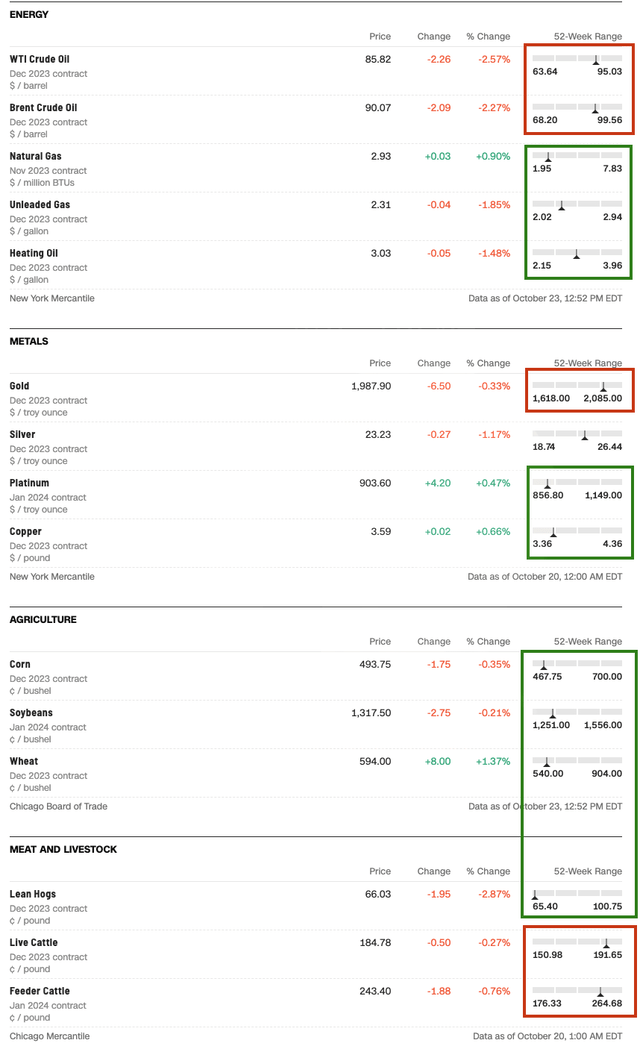

The high cost of commodities is a primary justification for many increases in living expenses. The prices of meat and oil(red) are at a 52-week high and those of agriculture, metals, and natural gas are at a 52-week low(green), which is one approach to assess the total situation.

Commodity price (Business insider)

We believe that the Fed is winning the war on inflation, but how long the Fed must maintain its high-interest rate will depend on the price of oil and sticky CPI components.

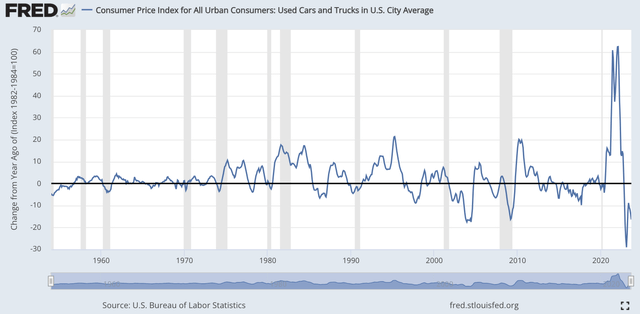

Apart from the cost of housing, used automobile prices are currently declining more quickly.

Used cars price (FRED)

This makes it more advantageous for service CPIs like insurance and maintenance costs to decrease. Two forces—the regulation price cap and the durable price decline—will limit the capacity of service businesses to raise prices.

Thus, the Fed’s plan to cut interest rates in 2024 remains intact. Consequently, TLT holders may benefit from this.

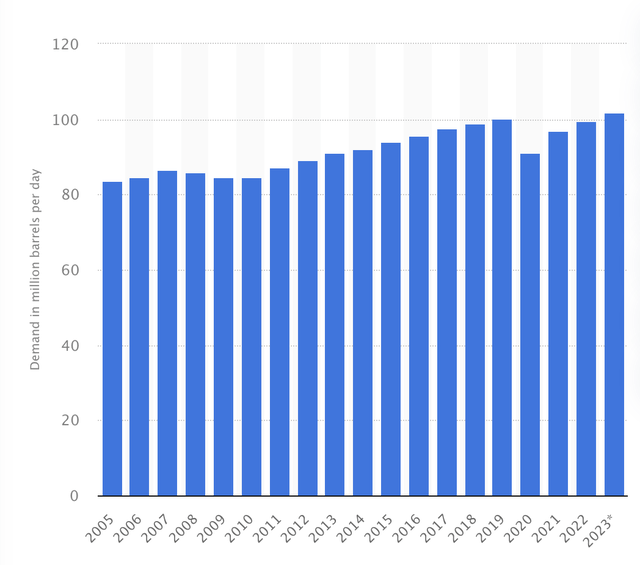

The Risk of an Oil Crisis Without Conflict

The black swan event is definitely the oil crisis again and without a total war. As demand for oil is still increasing in 2023 as it reached 100 million barrels per day level, this suggests that in the event of an oil crisis only, this will continue to push oil prices higher because the demand for oil has not materially deteriorated as a result of higher rates. In addition, since the US is not involved in the war, the Fed has no reason to buy bonds to bail out the US government but can be pushed to increase rates further to as high as 20%. Thus, we see the black swan event of TLT downside as significant.

Oil demand (Macrotrend)

Conclusion

Recent increases in long-term bond yields appear to reflect growing concerns about the potential for an oil crisis due to escalating regional conflicts in the Middle East. This suggests that the rise in long-term Treasury yields is not just a result of investors demanding higher returns to compensate for inflation, but also factors in heightened geopolitical risks.

While an oil supply disruption could exacerbate inflationary pressures, there are signs that overall inflation may be peaking. The Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes over the past year seem to be having a cooling effect on some previously red-hot sectors like housing and used cars. This is contributing to slower inflation in goods.

Meanwhile, potential catalysts like a Biden-Xi meeting in November offer an upside for bonds if tensions deescalate. So some short-term trading opportunities may emerge.

But even if the Fed is expected to cut interest rates in 2024, there is still a sizable downside risk to TLT in the case of an oil crisis. On the TLT, we would be neutral.

Read the full article here