In reviewing the pharmaceutical space, names often keep popping up as we write about other companies’ biggest competition, and Merck (NYSE:MRK) just so happened to be the one that piqued our interest enough to put together a dedicated analysis. Between the two titans of the oncology and vaccine spaces with Keytruda and Gardasil, respectively, we wanted to peek behind the curtain and see what more was going on at this Big Pharma powerhouse. We can’t exactly say we were blown away, but we weren’t underwhelmed either. This seems like one of those cases where they’re exactly where they need to be, exactly when they need to be.

The tentpoles

Merck’s business for the last several years has been dominated by two names, Keytruda and Gardasil, for better or worse. These strong products have given them the opportunity to sustain their size and market share, but the clock is ticking, and as we’ve discussed with other companies facing loss of exclusivity on their flagship products, it’s a treacherous path to navigate.

Keytruda

Despite backing their way into the IO space after Bristol-Myers (BMY) blew the field wide open with Opdivo and Yervoy, Merck executed a masterful pivot to turn Keytruda into a bona fide blockbuster that continued the company’s positive revenue trajectory. Keytruda crossed the $20 billion mark last year, and with label expansions rolling in hand over fist, this year is looking to push that number even higher with $12 billion already recorded in the first half. Management has been pushing the label expansions earlier and earlier into the treatment process:

-

They recently secured approval as a first-line treatment for HER2-positive gastric cancer in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy; first-line treatment in the HER2-negative case has been filed

-

First-line treatment for “advanced or unresectable biliary tract cancer” is under review

-

First-line treatment for “locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma” is under review

Merck has also been pushing Keytruda combination therapeutics to take full advantage of the immuno-oncology cascade:

-

LAG-3 inhibitor favezelimab + Keytruda is now in Phase 3 for colorectal and hematological cancers, mirroring Bristol-Myers’ Opdualag and the fianlimab/Libtayo combination therapy from Regeneron (REGN) for melanoma

-

CTLA-4 inhibitor quavonlimab + Keytruda in Phase 3 for renal cell carcinoma, joining the long list of CTLA-4 inhibitor therapies such as Yervoy, Imjudo (AZN) and other pre-clinicals being tested in combination therapies alongside PD-1 inhibitors (mostly alongside Keytruda, naturally)

-

TIGIT inhibitor vibostolimab + Keytruda in Phase 3 for melanoma and lung cancer, with the usual PD-1 suspects also keeping pace here too

Given that Keytruda is the most successful of the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor therapeutics, Merck got a small boost when Roche (OTCQX:RHHBY) disclosed Phase II results that showed their anti-TIGIT therapeutic tiragolumab in combination with their own PD-1 inhibitor Tecentriq demonstrated a small improvement in overall survival to Tecentriq alone.

All of this label expansion is good news, but at some point the marginal gain for each additional indication may start to wane, especially given that designing trials in earlier-stage patients requires more effort and volunteers in order to demonstrate statistical power. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on Keytruda’s exclusivity, with the five-year mark we harp on in the lifecycle timeline now in sight (2028 is the earliest quoted date for loss of exclusivity). No doubt the company will patent thicket anyone starting to ramp up the biosimilar pipelines, but with a less business-friendly legal system and increased scrutiny over drug pricing in the US (more on that later), there is a good chance their costs associated with defending Keytruda’s position will start increasing, causing some early erosion of the drug’s returns before the true loss of exclusivity sets in.

Gardasil

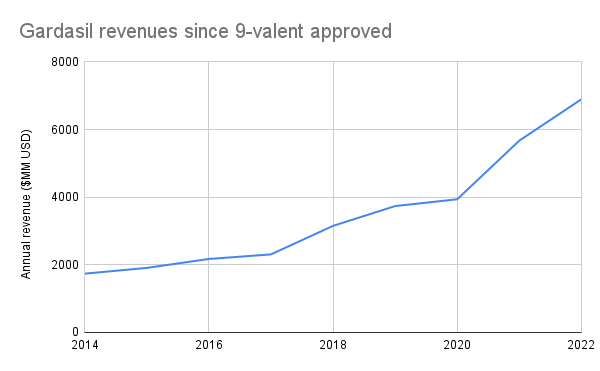

Fortunately, the latest iteration of Merck’s HPV vaccine, Gardasil 9, has a long runway ahead of it, with a reduced threat of biosimilar competition for the time being. International expansion has been the star of the show, with management calling out the growth in China on the Q2 earnings call, while expanded eligibility to women as old as 45 has also boosted the uptake in the West as well.

Merck 10-K filings + Author’s own work

At the beginning of September, CFO Caroline Litchfield commented at the Morgan Stanley 21st Annual Global Healthcare Conference that they are continuing to ramp up Gardasil manufacturing with a timeline through the end of 2025. She also commented that the company doesn’t think that demand has been fully saturated in the US and the West:

Vaccination rates are in the 70% [range in the US]. For a vaccine that’s preventing cancers, one could argue that should be in the 90s. So that’s an opportunity for growth. We have an opportunity for growth by vaccinating more males, and that’s especially in our ex-U.S. markets as we gain regulatory approval, and we’ll be driving for people to get that vaccine.

With that said, the tone of the commentary at the earnings call suggests this jump in the first half of the year is actually growth being pulled forward, with “timing of shipments” weighing on the potential revenues later in the year.

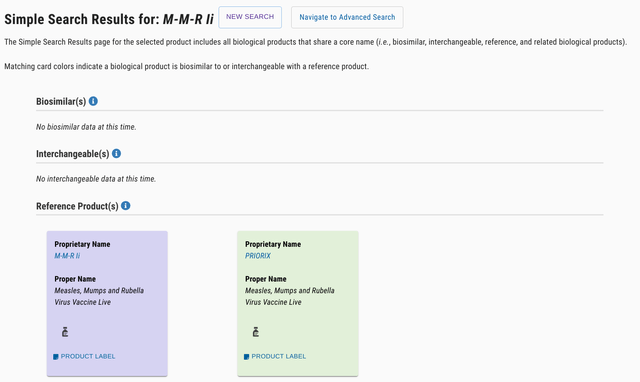

Vaccine regimens have a distinct business advantage over just about any other form of pharmaceutical, even antibody treatments, in that it’s very hard to replicate the exact cocktail of biological material necessary to elicit the desired antibody response in the patient. What’s more, even without patent exclusivity, a competing product (aka “second-generation vaccine”) is considered a biosimilar and thus has to go through clinical trials, demonstrate non-inferiority, etc. etc., which increases the barrier to entry. Case in point: Merck’s second-most profitable vaccine is their infectious disease mix M-M-R, a shot that even 90s kids like Derek can remember getting during elementary school, which only has one other product listed in the FDA’s Purple Book under the same Proper Name: Priorix from GSK, approved just last June.

FDA Purple Book

However, with Gardasil pulling down so much revenue and patent exclusivity tantalizingly close to expiry (2028, same as Keytruda incidentally), there is a biosimilar competitor that has made waves: Cecolin 9, produced by a Chinese manufacturer, using bacteria as the “bioreactor” for the vaccine components instead of Gardasil’s yeast bioreactor. Derek’s experience can attest that bacteria-based workflows are orders of magnitude simpler and cheaper than anything using a eukaryotic organism, even a single-celled one. In July, Cecolin’s developers published the results of a Phase 3 trial in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, claiming non-inferiority. Given that Merck management was keen to expand into low- and middle-income markets with their vaccine, they now have a potentially huge disruptor entering the fray with a markedly lower-cost-of-production second-generation 9-valent HPV vaccine.

New Opportunities

Continuing the narrative with the Big Pharma names mid-stream, there’s quite a lot coming up through the pipeline that should maintain the company’s current position, if not modestly accelerate growth some more.

Oncology

While immuno-oncology is dominated by Keytruda and the combination treatments, there are some interesting new developments coming out of Oncology around hematologic indications and new paradigms for treatment making their way into the clinic.

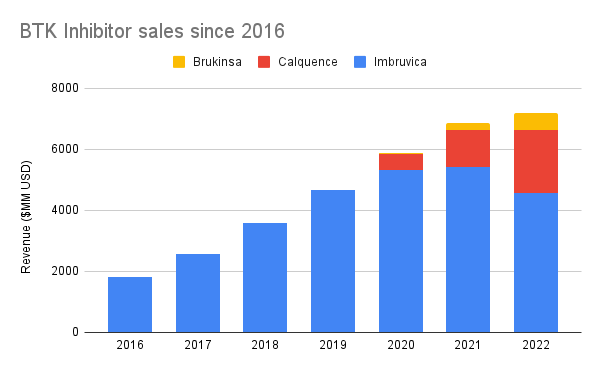

Heme-onc and Small molecule drugs

Merck has pushed into specifically heme-onc on the back of two small molecule treatments they picked up in acquisitions: nemtabrutinib and bomedemstat. Nemtabrutinib is currently in Phase 3 for CLL, and given that Lilly’s (LLY) reversible BTK inhibitor Jaypirca received advanced approval earlier this year, hopefully an advanced approval for nemtabrutinib will be forthcoming within the year. The mechanism is intriguing with the paradigm shift from irreversible BTK inhibitors such as Imbruvica (ABBV), which has lost market share to newcomers in the last few years, to reversible but strongly-binding BTK inhibitors.

Company 10-Ks + Author’s own work

Bomedemstat entered Merck’s portfolio when they acquired Imago earlier this year after escaping the Phase 1 morass that claimed so many other LSD-1 inhibitors; the FDA’s Clinical Trials website lists 16 studies that mention LSD-1 inhibitors, none in Phase 3. Of the ones targeting myeloproliferative neoplasms, other treatments such as TCP, INCB059872 and GSK2879552 have all had Phase 1 or 2 studies terminated due to lack of benefit or business decisions. At the Citi 18th Annual BioPharma Conference, head of Late Stage Oncology Marjorie Green called out bomedemstat as a rising star in the field:

“So those patients have a lot of burden. People who’ve got essential thrombocythemia myeloproliferative disorders, these are diseases that really have a negative impact on the quality of life and can lead to horrible malignancies. And so to have something as potentially disease modifying is very exciting to me.“

With an estimated 295,000 people in the United States living with these conditions and another 20,000 each year developing such conditions, the business opportunity does appear promising. What’s more, with LSD-1 implicated in other diseases, bomedemstat could have indications in immunology, endocrinology and neurology as well, which certainly makes a good story for Merck’s decision to acquire Imago for this pharmaceutical asset.

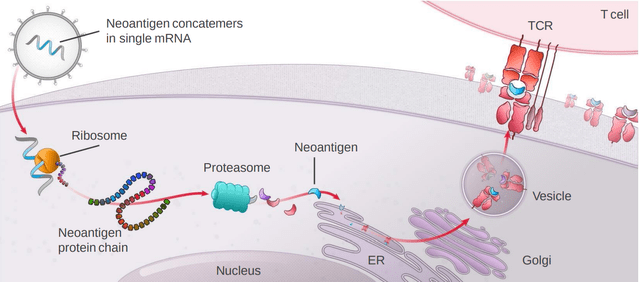

Moderna and the INT

In the wake of Moderna’s (MRNA) breakout success with their mRNA-based COVID vaccine, the spotlight is bright on them for the next major mRNA-based breakthrough. Merck has thrown in to the space with their partnership, working to spark an immune response in patients with cancer, tailored to that cancer, by introducing a single mRNA formulation encoding multiple “neoantigens” which are broken apart during translation and used to program the immune system.

Moderna program materials

Reading the transcripts, it’s obvious there are a few ways this treatment could be commercialized:

-

Use mRNA-based “individualized neoantigen therapy” (INT) as an adjuvant therapy to an existing standard of care, such as Keytruda. This mode of treatment is how the therapy got its previous, much snazzier-sounding codename as the “personalized cancer vaccine”.

-

Use INT to awaken “cold” tumors to the mainline treatments such as PD-1 inhibition; we saw similar approaches taken by Regeneron with their “co-stimulatory” bispecific antibodies in conjunction with Libtayo in prostate cancer.

-

Use INT in places where IO-based therapies have not worked or would have a low probability of working

The challenge here is one that sounds quite familiar in Oncology: do you swing for the fences with a rare unmet need or do you play “small ball”, bolt it on to an existing treatment, and get your foot in the door? Merck opted for the latter out of the gate by going for melanoma in an adjuvant setting, arguably already a “solved” problem space with Keytruda, but the INT seemed to make a difference where it mattered the most; Green called out the hazard ratio in cases of “distant metastasis” as 0.3 (that is, 70% increased odds of survival with the INT treatment as opposed to just Keytruda). You could probably make the case that Merck needed to see the proof for themselves before taking the big swings, which they are now doing in lung cancer and the “white whale”, pancreatic cancer.

Immunology

The other major acquisition Merck made recently was closing the deal for Prometheus Biosciences in June, which gave them a promising IBD drug candidate, MK-7240. Currently being trialed in Phase 2 for Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, there is definitely still a need for advancements in this space, and Merck is now poised to take advantage of a novel target in IBD to go after the massive market cap of names like Humira with a much more targeted therapeutic and a reduced risk of black box warnings, as mentioned by Merck Research Labs President Dean Li at the Morgan Stanley conference.

Endocrinology

There are several other smaller budding business opportunities, but the one with the largest upside has to be the GLP-1 agonist efinopegdutide. With so much hype surrounding the weight loss potential for drugs like semaglutide (NVO) and dulaglutide, the opportunity seems ripe to burst on to the scene. As it stands, though, leadership is wisely staying in their lane and trying to secure the initial approval for NASH, which itself affects a quarter of the world’s population. The Phase 2a clinical trial demonstrated significant reductions in liver fat versus semaglutide; whether this reduction translates into what could be considered “disease modifying intervention” will have to be proven in Phase 3, but the results so far are encouraging.

Risks

Naturally, a big pharma like Merck paints a huge target on their back for two reasons: they struggle with the marginal gains on their invested capital for new revenue streams,and they struggle to convince regulators that the existing revenue streams they make off of their life-saving blockbusters are reasonable.

Drug Pricing and the Inflation Reduction Act

In typical industrial-political fashion, the drug price negotiation stipulations rolling out in the United States as a part of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed last year have resulted in some dubious “portfolio management” to minimize the total number of drugs that may even be subject to negotiation in the first place. To wit: small molecule therapeutics like nemtabrutinib have four fewer years of protection from price negotiations versus biologics, a fact explicitly discussed during the Citi conference:

“…when you look historically, 60% of approvals have happened in the time frame where they might have been impacted by the IRA from drugs because of life cycle management. And so for [nemtabrutinib], we are strongly invested in developing this molecule and trying to bring an optimal regimen to patients and there are different ways of developing a small molecule in a way that you can still meet within the IRA time frame, some of them might have increased risk and how you develop that drug…“

That disparity in the immunity window, plus exemptions for things like drugs approved solely as “orphan drugs,” is causing fundamental shifts in the way that pharma companies approach their drug discovery and label expansions.

Green’s comments seem to suggest that companies may take a “kitchen sink” approach to label expansions in the future: blast as many label applications as you can within the first few years of approval and then toss the drug into the back drawer once the immunity wears off. Further commentary along this thread of discussion veers into speculation and is not appropriate for this forum.

Merck has opted not to go gently into this new model, however, and has fired back with litigation, alongside many other companies and names in the pharma space. Given drug pricing is top-of-mind for lawmakers and the public, the aging population placing more burden on Medicare, and the myriad stories of pharma companies’ practices of “evergreening” their blockbusters to suppress competition and maximize profit, it might not be a good PR look for these pharma companies to assert any kind of material damage. Given how long it will take for all of this squawking to shake out, we don’t think there will be any significant shifts one way or the other when all is said and done, it’s purely a matter of tactics and PR at this point.

Organic Discovery

The moderator at the Citi conference threw one hardball question at Marjorie Green, and it’s one we’ve seen in other big pharma companies: of the twenty or so Oncology drugs beyond early-stage development, eighteen were either acquired or co-developed under a licensing arrangement. Of the 32 or so unique compounds in the pipeline, only eight appear to be from in-house discovery. It’s absolutely no surprise that Merck would lean on acquisitions to bolster positions or even to bootstrap a new area of research, such as the Prometheus deal bringing them a promising Immunology flagship. The fact that these acquisitions have not appeared to assimilate into Merck proper, however, does seem quite surprising.

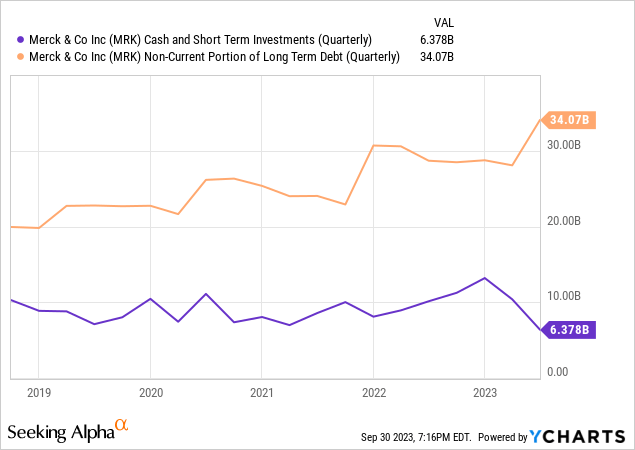

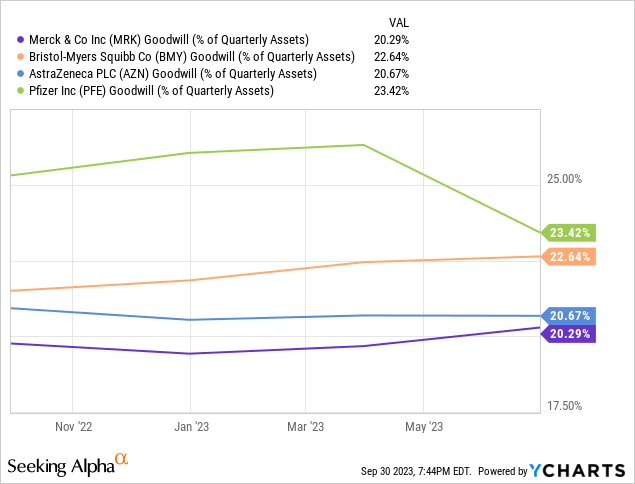

Given the easy money environment of the last several years, it was dead simple to start or acquire a clinical-stage startup, meaning healthy supply for the big names and healthy demand for the entrepreneurs. It would also seem that those whose exit strategy is acquisition would likely not be happy in the proverbial “golden handcuffs” of their new owner and at first chance would go out and repeat the process anew. The proof of the pudding will likely come in the next few years, how Merck’s pipeline fares as tight money restricts both the ability of clinical-stage companies to gestate and their own ability to secure financing:

In fairness, the goodwill on Merck’s balance sheet as a percentage of assets sits in-line with big pharma peers, so they aren’t massively overpaying for these acquisitions at least:

YCharts

Valuation

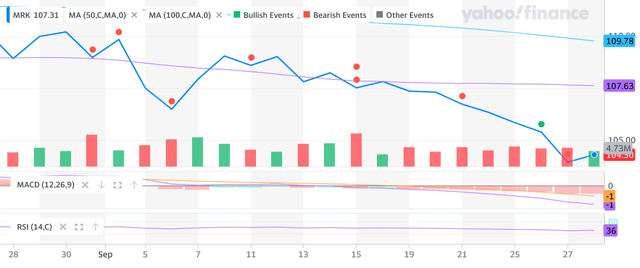

The puts and takes in Merck’s pipeline and operations seem to be balancing out, leaving us with a fairly-valued company to assess. Owner’s earnings have been growing steadily over the long term at roughly a 6.4% CAGR, a 30 basis point improvement from when we looked at them at the end of 2022 as a peer to Roche. At current prices, inverting the Gordon model gives us a 14.15% discount rate, up 138 basis points from ten months ago. Last year’s number, rounded to say 12.8%, feels a fairer premium to ask for Merck. The current price feels slightly on the pessimistic side, and the sheer number of bearish technical indicators seem to corroborate the price momentum at present:

Yahoo! Finance

All told, $115/sh feels like a fair assessment. That’s about 10% upside from current prices, which isn’t really enough to make us recommend buying, especially given the concentrated nature of their revenue streams and the choppy waters ahead.

Conclusion

Merck has managed their pipeline well to this point and been rewarded for it. Looking ahead, however, their management skills (in both pharmaceutical and business senses) are going to be tested as stiffening macro headwinds and looming losses of exclusivity threaten to prematurely derail the gravy train. The heavy dependence on a few breakout products and inorganic expansions of their pipeline and discovery footprint may not hold up for much longer. There is a small discount to be had for this risk right now, but it’s not really enough for us to insist it’s worth picking up over another big pharma name, all else held equal.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here