2023 has brought with it a surge in labor activism that the U.S. hasn’t seen in years.

On Wednesday, 75,000 union workers from Kaiser Permanente—one of the nation’s largest healthcare providers—started a three-day strike, setting the stage for the industry’s biggest strike in U.S. history.

The company’s doctors and nurses are following in the footsteps of autoworkers, screenwriters, actors, hotel workers, and other employees that have participated in walkouts this year.

The number of workers involved in strikes with more than 1,000 participants has reached at least 411,000 so far this year, the highest since 2019, according to data from Bureau of Labor Statistics and Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker.

But what makes this year particularly different is that the walkouts are mostly from private-sector workers, compared with the waves of public educator strikes in 2018 and 2019.

This year’s strikes have not only involved more workers than in recent history, but have also lasted longer.

Starting May 2, some 11,500 Hollywood writers went on strike for nearly five months before the Writers Guild of America reached a deal with major studios late last month. SAG-AFTRA members took to the picket line on July 13 and the union, which represents about 160,000 performers, is still in negotiations with studios, including

Walt Disney

(DIS) and

Netflix

(NFLX).

Actors, entertainers, and other SAG-AFTRA members want higher pay—including compensation tied to streaming viewership and residuals—better working conditions, and protection of their creative content from the use of artificial intelligence. The screenwriters had bargained for similar terms.

Recent economic conditions have led to what some economists see as a perfect storm for the rise of organized labor movements.

Elevated inflation in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly eroded the buying power of salaries. Although workers’ pay has increased, most Americans’ income hasn’t grown as much as rent and grocery costs. The sharp increase in interest rates has boosted borrowing costs, putting home purchases out of reach for many consumers.

Those factors have driven more workers across sectors to call for better pay, benefits, and working conditions. Roughly 65,000 educators from the Los Angeles Unified School District walked off their jobs for three days in March, followed by peers in smaller education districts and institutions across the country. About 20,000 hotel workers in southern California have staged a series of work stoppages since early July.

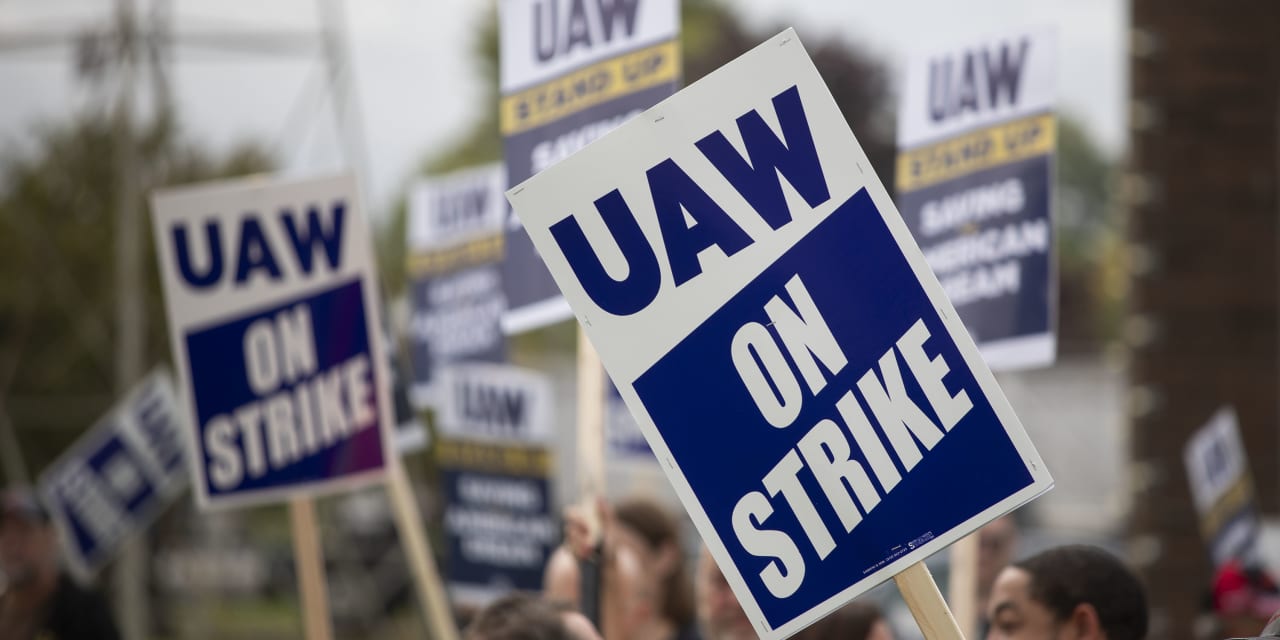

Since mid-September, the United Auto Workers has mobilized more than 25,000 workers to go on strike against Detroit’s Big Three car makers—Ford (F), General Motors (GM), and

Stellantis

(STLA). That equals about one-sixth of the 150,000 members that UAW represents across those firms. UAW has been adding striking workers in the past few weeks, and union leaders said the number could grow if necessary.

There might be more work stoppages to come. At the end of August, 26,000 American Airlines (AAL) flight attendants voted to authorize a strike if the company refuses to agree to “reasonable” contract terms. In late September, roughly 53,000 Las Vegas hospitality workers did the same as they started negotiations with hotels and casinos on new contracts.

The recent uptick in strike participation comes after decades of declining union membership and strength.

As of 2022, only 7.2 million, or 6% of the U.S. private workforce, were unionized, down from nearly 17% four decades earlier, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number of workers involved in strikes had fallen even more—to an annual average of 150,000 in the 2010s, from an average 1.5 million a year in the 1970s.

The most unionized sectors in America—manufacturing, transportation, and construction—represent an ever-shrinking share of the workforce. But weakening labor laws have made it harder for workers in growing industries—such as the service and delivery sectors—to organize new unions.

In addition, in the age of globalization, many companies can close U.S. facilities and move jobs overseas, while advancing technologies threaten to replace some human tasks with machines. All of this made it more difficult for unions to pressure companies and extract concessions during contract negotiations.

A prime example of this was in 2017, when 1,800 workers at

Charter Communications

(CHTR) walked off the job in protest of the company’s new healthcare and pension plan. But union negotiations went nowhere, and many workers stayed on the picket line for more than five years. It was one of the longest strikes—albeit at a smaller scale—in the U.S. history.

But signs of a union comeback have been growing in the wake of the pandemic. Since 2021, employees at more than 360

Starbucks

(SBUX) stores have voted to unionize. Workers at

Amazon.com

(AMZN) warehouses and drivers for ride-sharing apps like

Uber Technologies

(UBER) and

Lyft

(LYFT) have attempted to unionize as well.

For fiscal year 2022, more than 2,500 union representation petitions were filed at the National Labor Relations Board, up 53% from the previous year. At more than 400,000, the number of workers involved strikes so far in 2023 is already three times the annual average for the past decade, according to the BLS.

The labor market is seeing record-low unemployment rates—at 3.8% as of August—and many employers are scrambling to fill the openings amid increasing resignations and early retirements. The tight labor market could give workers more leverage in negotiations.

Hollywood writers have scored the first win, successfully boosting their income stream and protecting themselves as AI-generated content threatens to take their jobs. It remains to be seen whether other strikes can get workers what they want.

Write to Evie Liu at [email protected]

Read the full article here