On September 20, I wrote about the fact that labor productivity had not been growing the way it had in the past and that this factor was contributing a great deal to the reality that wages, particularly real wages, were not rising very fast. This was a major weakness in the argument the auto labor unions were making to justify their claims for large wage increases.

On September 21, Greg Ip, writing on the Wall Street Journal, fully supported my argument.

The title of his article: “American Labor’s Real Problem: It Isn’t Productive Enough.”

Mr. Ip writes:

“Yes, American companies still lead the world in design and innovation, but the resulting products increasingly are made abroad, especially in Asia.”

“Biden, like former President Donald Trump before him, wants to reverse this, through tariffs, subsidies and other government interventions. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and especially China certainly intervened plenty to help their manufacturers.”

“But attributing manufacturing performance to government policies alone is dangerous; it underplays how far Asian manufacturers have come in cost and quality and how far their American counterparts have slipped.”

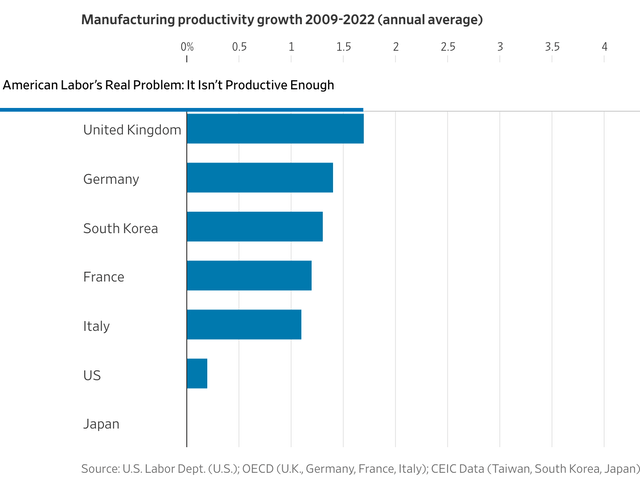

“Since 2009, manufacturing output per hour in the U.S. has grown just 0.2% a year, well below the economy as a whole and peer economies in Europe and Asia, except Japan.”

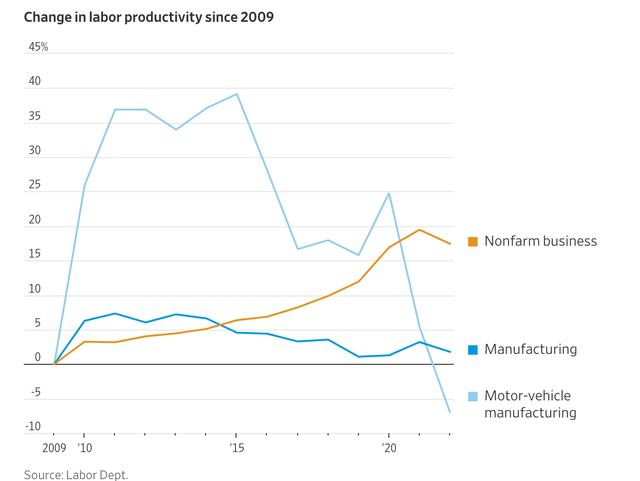

“In motor-vehicle manufacturing, the picture is especially bad: From 2012 through last year, productivity plummeted 32%, though some of this was no doubt due to pandemic disruptions.”

“For the United Auto Workers, it makes perfect sense to demand more pay and better work-life balance from Detroit’s three automakers. After all, workers throughout this historically tight labor market are getting exactly that.”

“But what makes sense to striking factory workers makes no sense for manufacturing as a whole.”

“Pay is ultimately tied to productivity: the quantity and quality of products a company’s workforce churns out.”

“And here, U.S. manufacturing companies and workers are in trouble.”

Labor Productivity Growth (U.S. Labor Department)

I have been writing about the slowdown of labor productivity growth in the United States for some time.

My argument has been that U.S. government economic policies have changed over the years, and this has directly resulted in the decline.

Here is another chart from Mr. Ip’s article.

Change in Labor productivity growth (U.S. Labor Department)

Note that Mr. Ip takes as his starting point the year 2009.

The year 2009 was the last year of the Great Recession.

Also, the year 2009 represented a transition period for the Federal Reserve.

Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, introduced a “new” structure for the Fed’s monetary policy around this time.

Previous to this change, the Fed had focused upon business investment as the primary target for its monetary stimulus. This focus was associated with the “old” Keynesian idea that to get an economy out of a recession and grow again, the central bank should lower interest rates, and stimulate expenditures on real business investment, and this would be the way for the economy to improve.

Mr. Bernanke, given his economic research on the Great Depression, proposed another approach. Mr. Bernanke believed that the Federal Reserve should stimulate the stock market, and rising stock prices would create a wealth effect that would generate more consumer spending.

Thus, the focus of the Fed shifted from business investment to consumer spending as the key to an economic recovery.

The problem with this is that business investment lagged the recovery and with the changed focus on business investment, the growth of labor productivity in manufacturing slacked off.

And, this slower growth in labor productivity contributed to an economic recovery that was the slowest economic recovery in the post-World War II period. Many analysts complained during the 2010s about the slow growth rate of the economy. The U.S. economy grew at an annual compound rate of 2.2 percent during the entire recovery period, the slowest recovery rate in the post-World War II period.

Stock prices rose very steadily during the recovery period, and generated lots and lots of wealth for those that could invest in the U.S. stock market.

One could argue that the economic recovery following the Great Recession was a very, very good one with low rates of inflation, the annual compound rate of growth of inflation during this period was 2.3 percent, unemployment remained very, very low historically, and the labor force participation rate rose to a very high level.

But, the economic recovery from the Great Recession produced two results that did not get the applause of the general public.

First, rising stock market prices…along with the rise in other asset prices…resulted in a major increase in income/wealth inequality in the United States.

Second, business investment lagged behind the results of earlier recoveries, and the consequence of this…the decline in the growth rate of labor productivity…kept wages and real wages from rising as fast as they did in early recoveries.

As Mr. Ip writes, “Pay is ultimately tied to productivity.”

The productivity growth was not there. The growth in pay was not there.

This is the reality that the autoworkers union must face.

And, it is the reality that the federal government must face in pushing for more and more deficits to stimulate the economy.

But, it is the reality of the situation.

Read the full article here