By Han Peng, CFA, Quantitative Strategist

China’s economic performance has been extremely disappointing since the lifting of lockdowns late last year. After an initial surge in activity triggered enthusiastic debates of a “V” or “U” shaped recovery, economic momentum lost steam as confidence failed to recover, and youth employment stayed stubbornly high. Subsequently, economic data has repeatedly missed forecasts, the government’s 5% GDP growth target is now being met with skepticism, and fears of a deflation trap have engulfed investor sentiment. At the heart of China’s economic troubles lies the property sector, and until policymakers proactively and sufficiently target rejuvenating it, prospects for China likely remain dim.

Not just economic stress, but financial stress, too

Amid the weakening economic backdrop, signs of financial stress have also emerged. Concerns over local government funding vehicle (LGFV) debts arose in May as Guizhou, one of the poorest provinces in Southwest China, became the first province to face insolvency and pleaded for a central government bailout. In mid-August, Country Garden Group (OTCPK:CTRYF) (China’s second-largest housing developer and previously its largest) missed bond payments, raising fears that property bond defaults may not just be limited to low-quality issuers. Also that month, Zhongrong Trust (a major trust company) defaulted on its payments to three companies that invested in its product, prompting questions about linkages between trust financing, the property sector, and contagion risks. The health of China’s financial sector is back in investors’ focus, drawing comparisons to the U.S. regional bank crisis from earlier this year.

Property sits at the heart of the problem

While diverse, much of the financial stress and deepening economic weakness can be traced back to the malfunctioning property sector. In 2020-2021, a debt-fueled property bubble prompted policymakers to curb home purchases and property developer financing. Two years later, these policies have overcorrected, resulting in plunging home sales, falling property prices, unfinished buildings, and struggling developers. The problem has become so severe that it risks dragging the whole economy into a prolonged and damaging downturn.

There are four channels through which property impacts the overall economic and financial health of China:

GDP Growth: The property and construction sector together represented 13% of China’s GDP in 2022. When combined with related sectors such as cement, steel, and furniture, this percentage increases to between 20% and 30%. The sizeable exposure to the overall property market implies that the government’s 5% GDP target will be hard to meet if the property sector doesn’t stop bleeding.

Households: The property sector has an outsized wealth effect compared to other investments in China. According to a 2019 People’s Bank of China (PBOC) survey, property accounts for 59.1% of Chinese household wealth, starkly contrasting to the United States’s 28.6%. Shrinking wealth, given the struggling property sector, is deterring consumers’ willingness to spend.

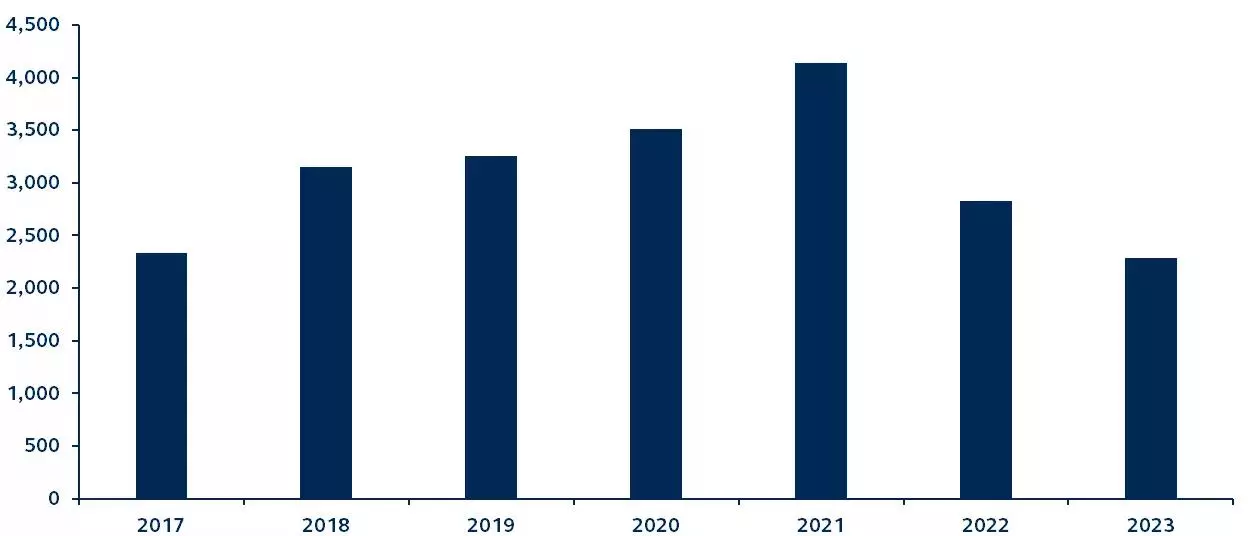

Local government: Land sales are traditionally an important revenue source for local government, accounting for about one-third of their revenue. Already wounded by COVID lockdowns, falling land sales are decimating local government’s budgets, fueling fears about LGFV debt, with some analysts describing LGFVs as the “black holes” of China’s financial system.

Financial system: Some trust products provide shadow bank financing to developers that, if a development project becomes distressed and default risks increase, potentially creating a dangerous loop between property and the banking sector.1 While the trust industry accounts for only a small part of China’s financial system, further strains in this space would certainly serve to dampen market sentiment at a time when investors are already nervous.

Failure of policymakers to stem the property market slump risks an escalating crisis of poorer households, indebted local governments, and weaker economic growth, threatening a vicious cycle of economic deterioration and asset price meltdown.

China land sales revenue through July of each year

Cumulative, $billions RMB

Data as of July 31, 2023. (Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China)

Policymaker actions

In fairness, policymakers have not completely ignored these downside risks. Yet, stimulus measures have inadequately addressed the weakness in demand. During the first half of 2023, policymakers focused on completing unfinished buildings and gradually reducing restrictions on developer financing. However, restrictive mortgage policies and curbs on house purchases were mainly kept intact in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities, nullifying the effects of the PBOC’s mini-steps of rate cuts – the 5-year loan prime rate (the key rate for mortgages) has only been cut 45 basis points, in total, over the past two years.2

More recently, there have been hints of a more proactive approach to the property sector’s woes. In the July politburo meeting, the well-known government slogan “houses are for living in, not for speculation,” was dropped, and policymakers noted the “changing dynamics of demand and supply in the property sector,” raising hopes that demand-stirring policies are on the way. However, policy follow-through has so far been gradual as China’s government is still wary of overstimulating. Encouragingly, since late August, policy easing has gathered some momentum with the relaxation of mortgage restrictions in Tier 1 cities, but more is likely needed to drive a sustained recovery.

Investment implications

Prudent policymaking is essential in an economy like China, which has a tendency toward excessive leverage. Nevertheless, there is a limited amount of time to act before the property sector’s struggles pull down the whole economy, and the longer the delay, the more drastic policy action it will require to counter the downward trend. The property sector’s issues are among the factors impacting China’s outlook and causing concern for global investors. Without adequate action from policymakers to address market weakness, investor enthusiasm for investment in China will likely be subdued. However, history has taught that China frequently makes policy adjustments during the bleakest times – an environment that can create investment opportunities for active investors.

1 Trust product is a wealth management product launched by trust companies which are often linked to shadow banking and attract high net worth investors through high potential returns.

2 Tier 1 cities are the four most economically developed cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou); and Tier 2 cities are moderately developed cities that are typically regional economic centers or provincial capitals.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here