Main thesis

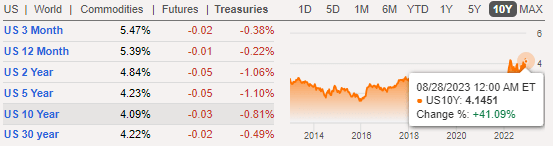

Relative macroeconomic stability, declining but still persistent inflation and a strong labor market have created an environment for a more cautious but hawkish approach by the Fed. To summarize Powell’s speech at Jackson Hole, the Fed is pleased with the current trends and, if they persist, they will not change anything, but if they see these trends fading, or suddenly begin to change, they will react to this and tighten policy. Against this background, the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds rose to the high of, 2022 and stay above 4%.

Seeking Alpha

However, I’m more of a believer in the ‘Higher for shorter’ scenario, given how quickly things tend to break down after the Fed’s aggressive rates hiking.

What’s wrong with ‘Higher for longer’?

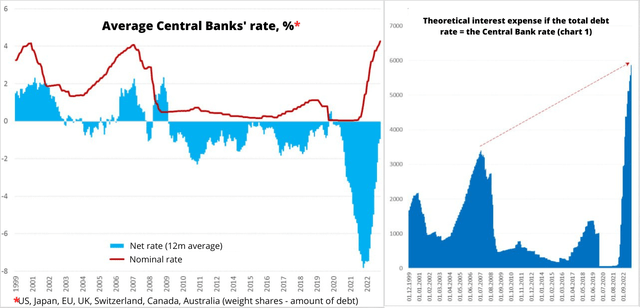

In one of my previous articles, I explained why the key to the Fed’s success in reducing inflation is to raise rates to a restrictive level, and then hold it for as long as it takes. The main problem with this is the economy simply cannot operate at these rates for much longer.

This is best seen in a simulated situation in which all debt is serviced at the rates of central banks (weighted average). In this case, interest expenses amount to $5.9 trillion, which, even in relation to GDP, will be well above average.

TruEcon

On the other hand, in the financial system, when rates rise, there are losses, sometimes small, and sometimes they manage to unleash a global crisis. We don’t know how serious the damages are yet. But we know how quickly the situation can develop in such an environment. This spring in the US, three (four with Silvergate bank) have collapsed with assets of >$500 billion, and in Switzerland a systemically important bank with assets of $60 billion failed. Back then, the regulators managed to take it under control. First Republic (OTCPK:FRCB) was sold to JPMorgan (JPM) with a guarantee to cover losses, while Credit Suisse merged with UBS (UBS). However, the losses from the system didn’t really go anywhere.

Banks & real estate

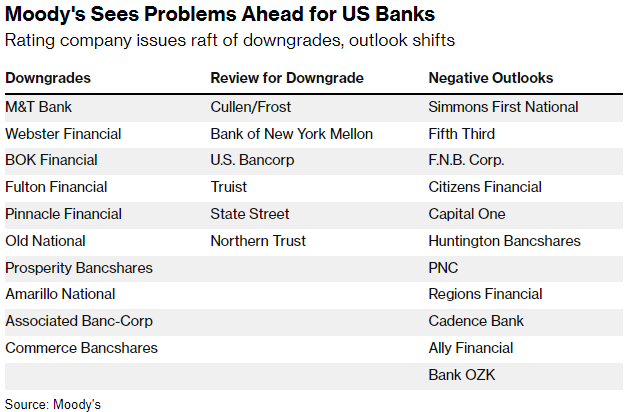

When I am talking about losses in the system, I don’t necessarily mean some events in the future. There are enough problems here and now, it’s just that the process is “frozen” until the next bank runs. A month ago, Fitch downgraded the US rating, keeping the outlook stable. Later, Moody’s decided to do the same thing, but with the banking sector. With a delay of several months, experts downgraded the ratings of 10 small and medium-sized US banks and put the ratings of such giants as U.S. Bancorp (USB), BNY Mellon (BK) and Truist (TFC) on review for downgrade.

Bloomberg

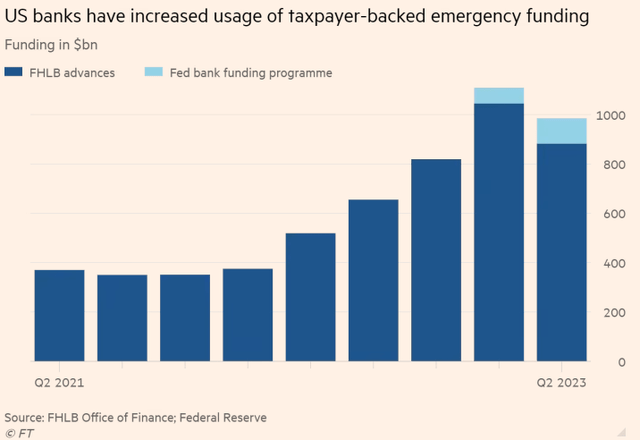

According to the recent stress test of banks by the Fed, in the event of a serious recession, the projected losses will amount to $541 billion. This is not much, although there have always been questions about such “tests”. Despite the recent stability in the sector, banks (mostly regional) still relied on almost a trillion dollars in government funding in Q2 (expensive FHLB advances), according to FT.

FT

It is important to understand here that the exposure of regional banks to commercial real estate is massive, so these two sectors are very closely connected.

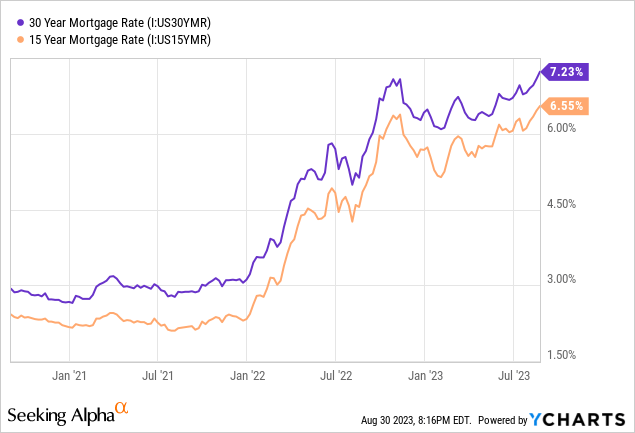

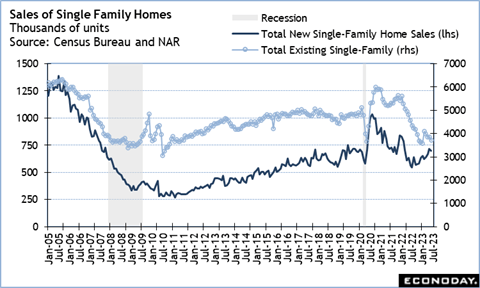

The US housing market continues to remain, on the one hand, in the mode of shortage of supply of finished housing, on the other hand, the unavailability of this housing against the backdrop of high rates and prices. Prices are becoming increasingly more unaffordable for consumers as mortgage rates rise.

Sales of private homes in the US secondary market in July fell to the level of 3.6 million homes a year. At the same time, the supply on the secondary market covers sales for only ~3 months, which is very small by historical standards. The average settlement payment on a mortgage in the secondary market is at current rates of more than $2,000 per month and more than half of the average salary, which is the highest since 1984.

Econday

Against the backdrop of a shortage of existing houses, prices are not falling, despite the collapse in mortgage applications to a 28-year low. Moreover, it looks like prices are still rising (accounted for seasonality).

FRED

So the market’s volume shrinks, but nothing is getting cheaper. In fact, with some corrections, this is an echo from 2007, when an almost identical situation was observed. The problem is that after 2008, many households simply dropped out of the market for many years. Therefore, the risks have shifted from private households to institutions. A decent part of this has a credit component at low rates. So if there are delays and defaults at such giants as Pimco, Blackstone and Brookfield, as in March, then the domino effect can spread to a very large number of sectors of the economy in my opinion.

Japan factor

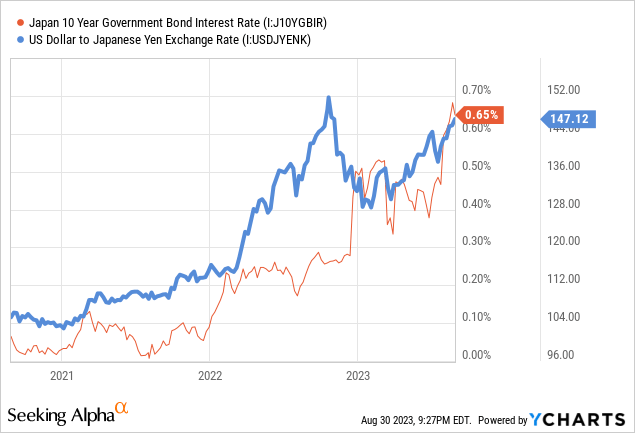

Since the beginning of the year, the Bank of Japan has bought ¥81 trillion worth of government bonds, or $600 billion. This is compared to all budget expenditures for this period (¥114 trillion), more than annual budget revenues (~¥80 trillion) and far exceeds the planned volume of government bonds issue.

Against this background, the Japanese yen is moving towards its 30-year-high, which could trigger interventions again, and JGBs are at 0.65%.

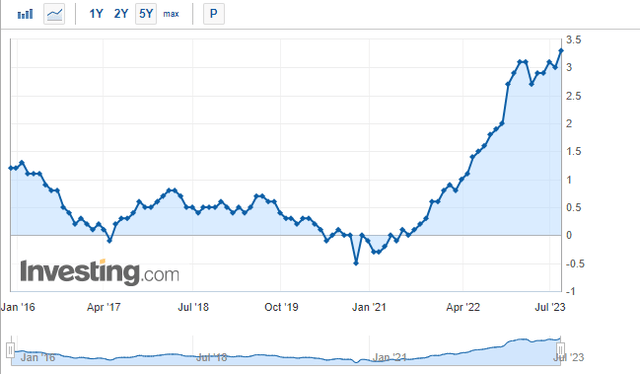

Thus, BoJ’s core inflation reached 3.3%, and although modest by world standards, still a record for Japan.

Bank of Japan CPI YoY (Investing)

Now everything depends on the actions of the regulator, but I believe the problem is that the regulator is no longer in control of the situation. The most logical step now would be to stop holding bond yields tightly, but that’s not possible given the debt system that’s built up in Japan and around the world. The devaluation of the yen is a very painful process, but as long as the regulator continues to maintain an ultra-soft policy (negative rates + YCC), this process is inevitable in my opinion.

There are enough regions in the world where something can break (for example, China which is facing deflation or Germany with Deutsche Bank, which I think has a reputation comparable to failed Credit Suisse). It’s just that Japan has 10 trillion in external assets, and it is there that the real problems are now visible.

How to play it: TLT vs TLTW

The iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond BuyWrite Strategy ETF (TLTW) is a lesser-known fund in comparison with NASDAQ:TLT. It is smaller and newer overall, being released in 2022 and having $650 million in AUM.

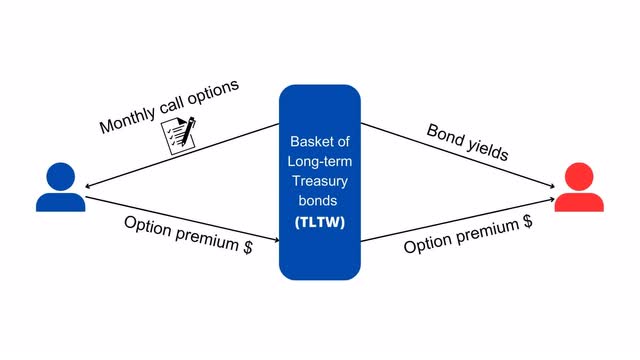

Well, TLTW simply holds TLT while writing (selling) one-month covered call options to generate income. So the mechanism looks like this:

Author, Traphagen CPAs and Wealth Advisors idea

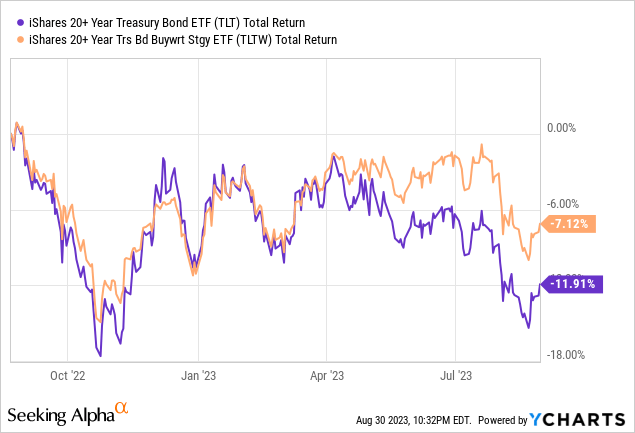

It is worth noting, TLTW has performed way better than TLT since the exception.

However, Long-term treasuries stayed steady and had been drifting higher, not spiking. The thing is, TLTW has a limited upside in my scenario for one simple reason: the underlying TLT would simply be called away if it actually ‘spikes’. I am expecting fast shock scenarios, for the reasons described above, so TLT works way better for me. At the same time, if you are hedging your equities against the fast and heavy recession (which causes long-term bonds to run up fast), your covered calls become a burden for decent returns.

That being said, I’m sticking with TLT, but there are scenarios where TLTW can continue outperforming (flat/range-bound underlying).

Conclusion

Despite the conviction of a large number of market participants and the Fed itself in a ‘higher for longer’ scenario, I do not believe that this is possible with a debt system that has been building for decades. The current economy simply cannot perform under such rates for long, in my view.

Because of this, I am very bullish on Long-term treasuries and sticking to TLT.

Read the full article here