The capitulation of bearish investors seems to be a popular trend on Wall Street.

After months of unexpectedly strong stock market performance, more big-name investors have shuttered bearish bets or changed their dour tune—even as the stock market has begun to edge lower.

June and July short-covering was the largest over a two-month period in the past seven years among Goldman Sachs’ hedge fund clients, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Morgan Stanley strategist Mike Wilson, who has been sharply criticized for his negative views on the market, recently turned less bearish.

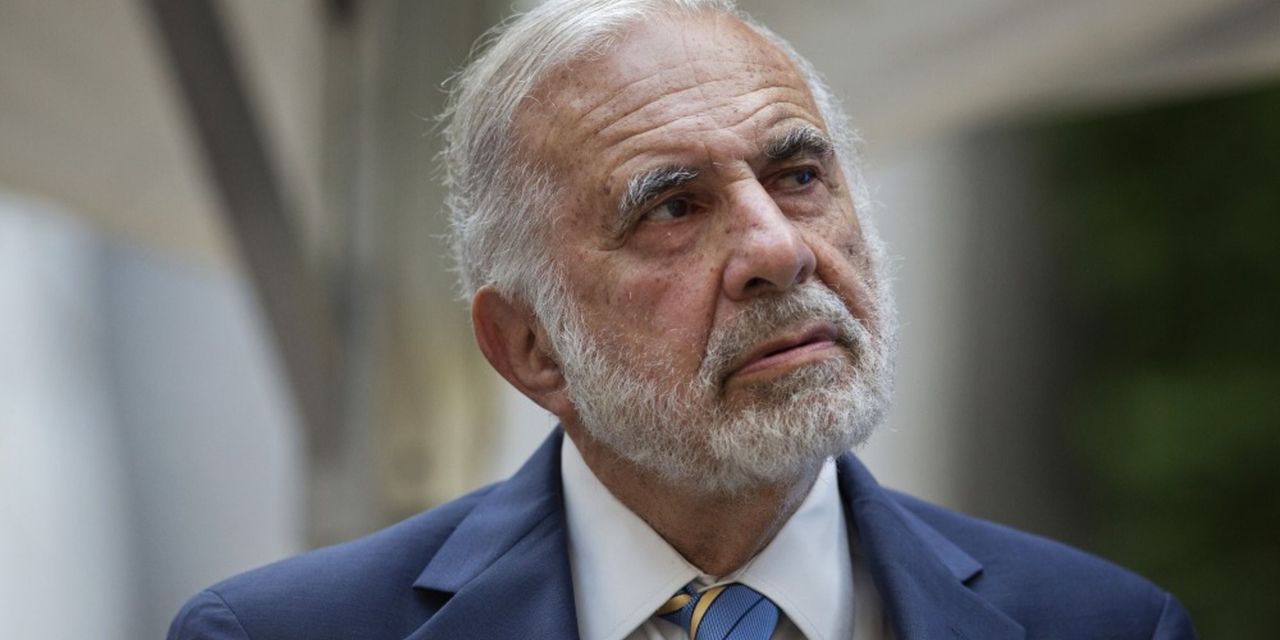

Carl Icahn, the activist investor, has decided that he, too, has wagered enough against the stock market advance. In a letter sent earlier this month to

Icahn Enterprises

(ticker: IEP) investors, he pledged to focus less on hedging stocks to express bearish views and more on what he is known for.

“Activism is the best investment paradigm,” he wrote.

The market mob might delight in the difficulties of well-known investors. But schadenfreude is the wrong reaction—especially for those who, mostly through luck, were properly positioned for the 2023 rally.

Capitulation at the market’s highest levels is coinciding with a subtle shift in the market narrative: Many investors are increasingly fretting that corporate earnings are slowing, which should bode ill for stocks.

Oppenheimer strategist John Stoltzfus recently told clients that

S&P 500

companies’ earnings seem weaker than expected for the second quarter thus far. He noted that earnings are down 7.8%, compared with an expected 6.4% decline.

Anyone who misses the significance of that surely understands this: Fitch recently downgraded the U.S. debt rating. Moody’s downgraded 10 regional banks and put others on notice that the same may happen to them. And 10-year Treasury yields have recently been above 4%, a level that has historically been bad for technology stocks, which have led the market higher this year. That’s because the discounted-cash-flow models used to value stocks are adversely impacted by higher interest rates.

Add to that the percolating financing troubles in the real estate sector and uncertainty about the odds of a recession, and you have the recipe for financial indigestion.

If you agree that the market narrative is changing—and you think it is premature that bearskin rugs are suddenly in vogue—consider protecting some of the extraordinary gains of 2023.

Hedging expenses remain reasonable. The

Cboe Volatility Index,

or VIX, remains below its long-term average of 19. Michael Schwartz, Oppenheimer’s chief market strategist, has told clients to buy three S&P 500 November $4450 put options to hedge a $1 million portfolio. If the market falls 10%, he says the hedge would offset about 95% of any losses. (Puts give holders the right to sell a specified asset at a set price within a set period.)

Most bullish investors wait to hedge, or lock in profits, until they panic. The end of summer will bring many events that could prompt investors to sell stocks. The November expiration covers many key events that include the September and October trading months, which have historically delivered major market declines, several meetings of the Federal Reserve’s rate-setting committee, and loads of key economic data that will be parsed for clues on inflation.

If stocks rally into the fall, money spent hedging will be lost. Should that happen, of course, you can capitulate.

Steven M. Sears is the president and chief operating officer of Options Solutions, a specialized asset-management firm. Neither he nor the firm has a position in the options or underlying securities mentioned in this column.

Email: [email protected]

Read the full article here