Staunch critics of China’s development model have been skeptical of the country’s rise as an economic superpower for many years and for various reasons. However, repeated warnings of an impending economic crisis never materialised until the pandemic and Draconian interventions by the government finally took a toll on China’s economy. These mistimed warnings have not only undermined the credibility of these critics but have also appeared to dull investors’ aversion to risk.

For a period of time, investors seemed overly accommodative to negative developments in China and would downplay risks so long as there was still “immense potential” in the economy. China’s sheer population size, increasingly affluent middle class, rapidly modernizing economy, and technological progress, have only made it easier for investors to cast aside any doubts over its seemingly unstoppable rise to power.

When we published our own critical assessment of China last year titled “China May Be ‘Uninvestable’ After All” – 17 October 2022, we too received quite a lot of pushback from readers. To our surprise, even the threat of a rapidly deteriorating political environment driven by the Chinese politburo’s increasingly authoritarian economic and foreign policy has failed to dampen investor sentiment. Since our article was published, however, events in China have only continued to unfold in ways that add further support to our view that China may be uninvestable after all.

Uncertainties To Success Or Evidence Of Failure?

One can either take an optimist’s view and treat negative events as uncertainties that could potentially delay China’s inevitable rise. Or one can take a pessimist’s view and treat the same negative events as evidence that the country is potentially on a path to failure. We are increasingly leaning towards the latter.

Not only do we think that the potential rewards no longer justify the risks associated with investing in China, but we also think investors should urgently reassess how economic stagnation in China could potentially undermine their portfolios.

Many economists are also increasingly convinced that China is precariously sliding into economic stagnation. A quick search on Google for “China Lost Decade” will yield a mountain of recent articles presenting a dire outlook for China by drawing similarities to Japan’s Lost Decade in the 1990s.

Nobel laureate Paul Krugman recently shared on his New York Times column that he thinks China could probably end up in a worse situation than Japan’s Lost Decade. Krugman highlighted China’s deteriorating demographics, including the middle-income trap, declining working-age population, and rising youth unemployment rates. Other prominent economists including Richard Koo of Nomura Research think that China will face a “balance sheet recession”, where consumers and businesses are looking to repay debt instead of borrowing and investing. Without decisive and substantial fiscal stimulus, economists are concerned that China is more likely to drift toward economic stagnation than to see the rebound that many investors have been waiting for.

China’s Challenges Are Structural, Not Just A Blip

China’s long-term developmental challenges are structural in nature as the low-hanging fruits of catching up to the developed world have been mostly exhausted. China’s maturing economy will need to evolve to be more self-sustaining without having to rely on exports as manufacturing wages rise, and its well-educated youths will demand better wages and white-collar jobs.

However, economies do not evolve naturally into a complex ecosystem of high-value industries supported by innovative research institutions and a highly-skilled labour force. This is especially true if the rapid development of an economy has been mostly dependent on exports to other high-income nations. Without policy initiatives by the government to stimulate domestic demand, install innovative research institutions, and nurture a highly educated and skilled workforce, economic growth is unlikely to be sustained as wages and labour productivity catch up to the developed world.

Perhaps China’s own success is also its biggest weakness. Having expanded its economy so rapidly within just a single generation, the country has not had the luxury to rebalance and restructure its economy to focus on domestically driven growth.

Demographics Determine Economic Destiny

In terms of demographics, there are also worrying signs that China’s history of suppressing nationwide fertility rates for decades will begin to place an increasing burden on a shrinking working-age population to drive growth and finance higher healthcare spending.

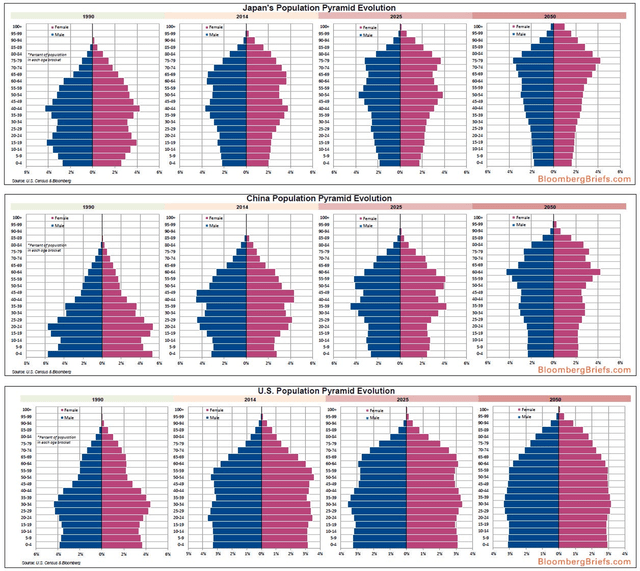

Below is a series of charts comparing the expected evolution of China’s population pyramid to that of Japan and the U.S. Notice how China’s population pyramid closely resembles that of Japan, with a widening top and a narrowing bottom, reflecting an ageing population being supported by a shrinking working-age population.

U.S. Census Bureau, Bloomberg

In contrast, the U.S. is expected to maintain a relatively well-balanced population pyramid with a wide bottom and a narrowing top, reflecting a healthy and stable working-age population over time.

One of the most grossly underestimated factors driving the dynamism of the U.S. economy is its immigration policy. The U.S. has been able to attract and retain the most talented students from around the world due to its Ivy League universities and research institutions, while many businesses also choose to operate and expand in the U.S. due to the high consumer spending. Almost 70% of U.S. GDP is made up of private consumption.

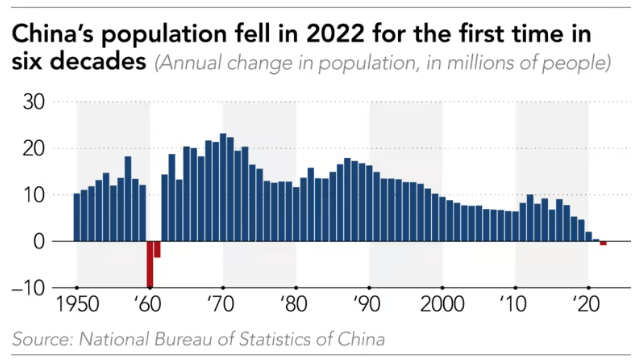

Not only does China lack many of the qualities and advantages that we have mentioned above, but China is also facing an exodus of wealthy citizens and talent amid fears of a renewed government clampdown on private sector debt, corruption, capital flight, and individual freedoms. Such actions are only likely to exacerbate the problem of a shrinking working-age population as China’s population fell for the first time in 2022.

Nikkei Asia, National Bureau of Statistics of China

China’s Challenges Are Inevitably Political

Often, political risks are conveniently swept aside during economic discussions as investors have grown accustomed to the relatively stable and well-oiled democratic systems of the developed world. However, it would be a grave mistake to assume that the Chinese economy will operate on the same economic principles as the rest of the democratic world.

Throughout the pandemic, there were clear indications that the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) top priority was to assert the party’s dominance and control over the country. In hindsight, China’s zero COVID strategy and its decision to not use U.S. vaccines also showed how deeply entrenched political ideology is at the centre of the government’s decision-making body.

Where Is The Stimulus?

This brings us to the frustrating delays and lack of meaningful stimulus by the Chinese government to reignite growth for its rapidly deteriorating economy.

From a policy perspective, it is understandable that any attempts to stimulate China’s economy meaningfully would mean undermining some of its previous efforts to rein in local government debt and excess leverage in the real estate sector. Thus, a massive stimulus is likely to backfire on plans to reduce structural indebtedness. A massive stimulus may also be viewed as a form of backtracking or policy failure by the government.

However, one should also understand that this build-up of bad loans across the local governments and real estate sector neither happened by chance nor by free market forces. China’s excess leverage and bad loans are due to the side effects of central planning over the years. This is demonstrated by occasions when the Chinese government would exercise its power over the banking sector by issuing orders to state-controlled banks to finance costly infrastructure projects and lending to the real estate sector. State-owned enterprises have also been called upon in the past to step in and acquire troubled and heavily-indebted firms.

As China’s economy deteriorates rapidly, the lack of decisive fiscal stimulus by the government is threatening to drive the economy into a period of economic stagnation. Despite the urgency for stimulus, there is unfortunately no simple solution to reignite growth. China’s leaders are unlikely to seek to reconcile with the West, given that doing so would be a show of weakness.

Investors should reassess China’s growth story and decide if the rewards are worth the risk. From our perspective, China not only looks like it is sliding into a period of stagnant economic growth but potentially a Lost Decade.

Read the full article here