A guest post by D Coyne

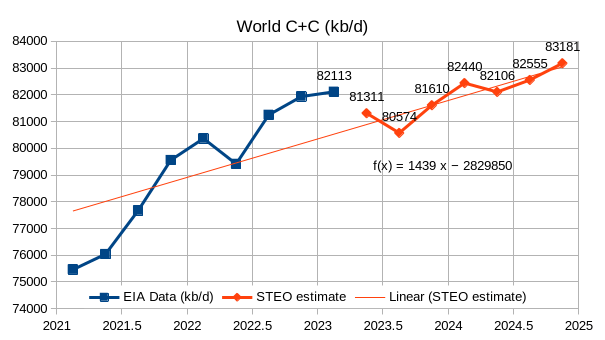

The EIA’s Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO) was published in early July. The chart below estimates World C+C by using the STEO forecast combined with past data from the EIA on World Output.

This month, we have actual EIA data for 2023Q1 which increases the annual rate of increase for the forecast period compared to last month by 600 kb/d, part of the reason is an 800 kb/d forecasted drop in output from Q1 to Q2 of 2023. If we use the 2023Q1 to 2024Q4 trend, the annual rate of increase is 911 kb/d, about a 100 kb/d increase from last month’s estimate. The trend from 2022Q1 to 2024Q4 is similar at about 916 kb/d. If this forecast through 2024Q4 is roughly correct, I expect increases in output after 2024 will be considerably lower, I also think this STEO forecast is optimistic. Annual average output in 2022 was 80.74 Mb/d and increases to 81.4 Mb/d in 2023 and to 82.6 Mb/d in 2024. These annual averages are 0.25 Mb/d less in 2023 and similar for 2024 as last month’s estimates.

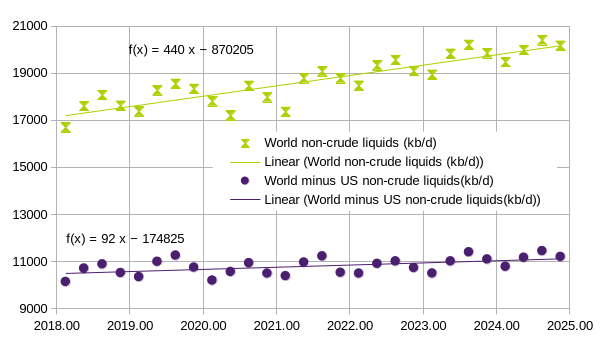

The chart above considers World liquids output that is not C + C output, mostly NGL and biofuels as well as refinery gain and compares the World total with the World minus the US. About 79% of the annual increase in liquids that are not C plus C comes from increases in the US.

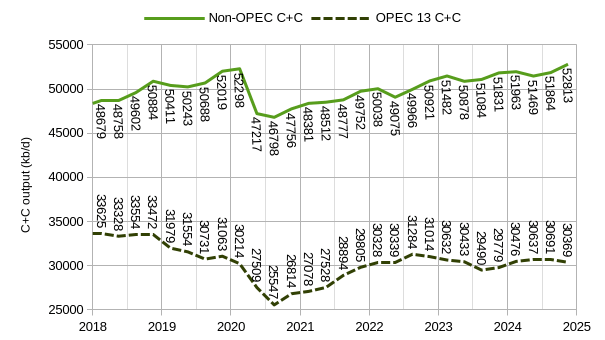

The chart above compares OPEC 13 output with non-OPEC output with the last 7 points of each series being from the STEO forecast. OPEC output increased quickly to about 30 Mb/d from about 25.5 Mb/d over the July 2020 to Jan 2022 period and has since stalled at about 30 Mb/d with a decrease from the post-pandemic peak of 31.3 Mb/d in 2022Q3 and is expected to fall to 29.5 Mb/d by 2023Q3 and then recovering to 30.7 Mb/d in 2024Q3. This is different from the announced quotas plus recent output from Iran, Libya, and Venezuela, so the EIA must believe the quotas will be changed. Most of the expected increase in World output in the STEO forecast comes from Non-OPEC producers. About 1900 kb/d from 2022Q4 to 2024Q4 or roughly 950 kb/d each year.

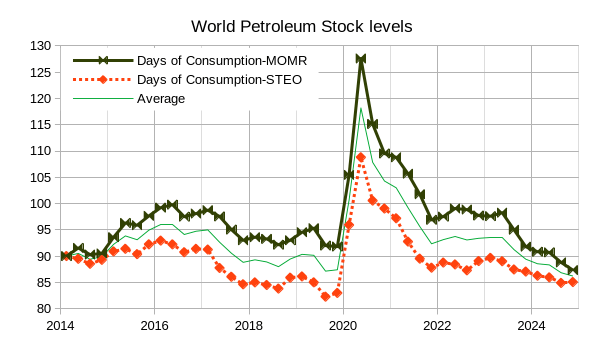

The chart above considers World petroleum stocks using data from both the EIA’s STEO and OPEC’s MOMR. I assume the stock level at the end of the first quarter of 2014 is equal to 90 days of that quarter’s consumption of total liquids for the World. This choice is arbitrary, but typically nations try to maintain about 90 days of stocks and at this time World prices were high so stocks were likely at at least this low a level. Using this assumption and the STEO supply and demand data results in very low stock levels at the end of 2019 (about 83 days of consumption), where the MOMR estimates result in a higher stock level of about 92 days of consumption at the end of 2019. The green line is the average of the two estimates. The expectation is that World stock levels below 90 days should lead to increasing oil prices and stock levels above 90 days should lead to falling oil prices. Sometimes market fear of a supply disruption (such as a War near Russia or in the middle east) can lead to price spikes unrelated to stock levels.

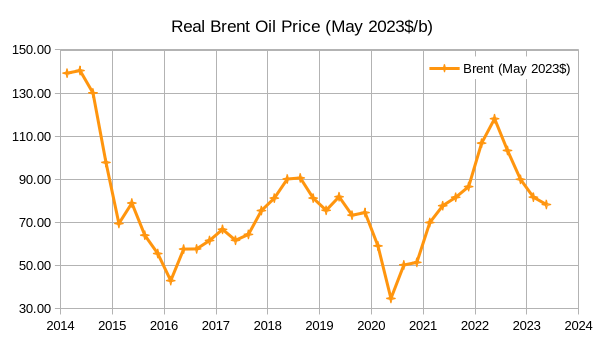

Considering the real oil price chart above for Brent Crude in May 2023 $/b, the green average stock level line gives a fairly good indication of rising or falling oil prices with the exception of 2022 when fears over Russia’s invasion into Ukraine created a price spike. On the basis of the green stock level line falling below 90 days in late 2023, we might see rising oil prices at that point. Note that for the OPEC stock level forecast after 2023Q2, I assumed Iran, Libya, and Venezuela continue to produce at their June 2023 level over the ensuing 18 months and that the other ten OPEC members produce at the announced levels as of the most recent OPEC announcements (this includes the announced voluntary cuts) through 2024Q4. Obviously, the forecasts won’t be correct, but if they were, the stock levels would be as shown and oil prices might rise in 2024.

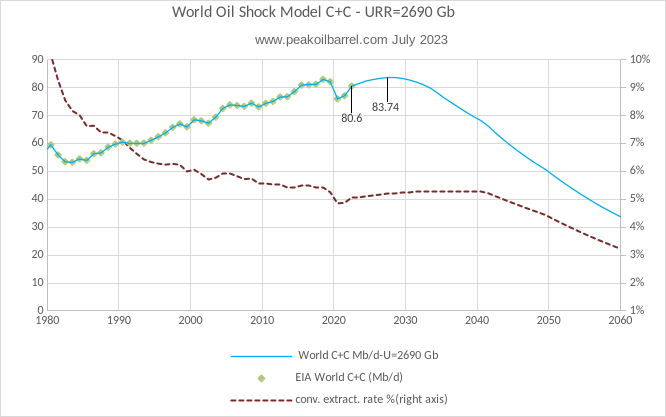

The chart above uses Paul Pukite’s Oil Shock Model to estimate future output with the assumption that a transition to electric transport reduces oil demand to less than supply by 2033 (+/- 2 years). The extraction rate shown on the right axis is for conventional oil only, a separate model is used for both tight oil and extra heavy oil. Output peaks in 2027 at 740 kb/d above the 2018 peak of about 83 Mb/d.

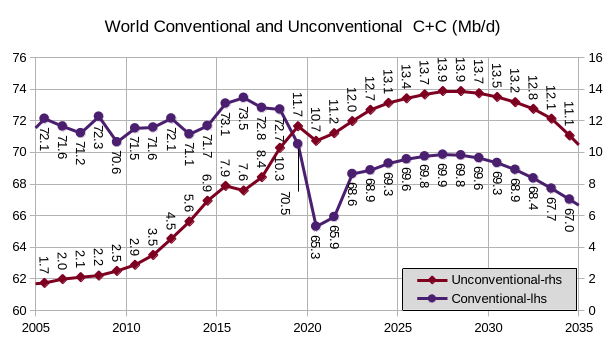

The shock model can be divided into conventional and unconventional oil scenarios where unconventional oil consists of tight oil and extra heavy oil with API Gravity less than 10 degrees. The conventional scenario peaked in 2016 at cumulative output of 1273 Gb and has a URR of 2520 Gb. The unconventional scenario peaks in 2028 at cumulative output of 77 Gb and the URR is 170 Gb. The combined model peaks in 2027 at a cumulative output of 1624 Gb.

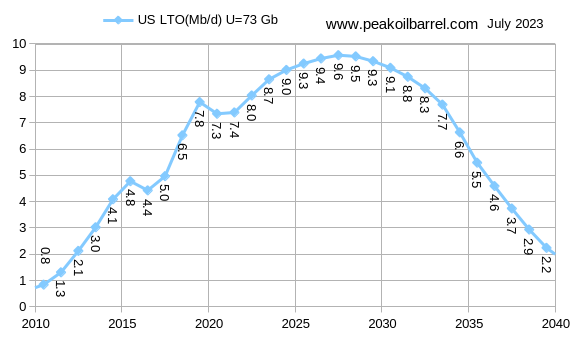

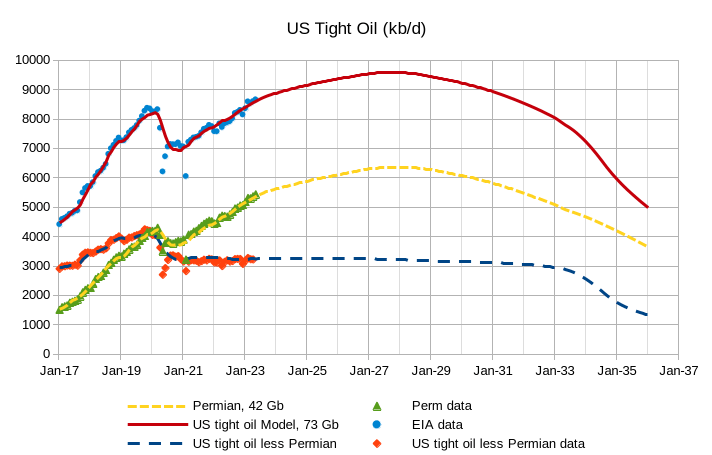

The US tight oil scenario above is a slight revision to the scenario presented last month. It peaks in 2027 at 9.6 Mb/d and has a URR of 73 Gb, slightly bigger than last month’s scenario (72 Gb last month).

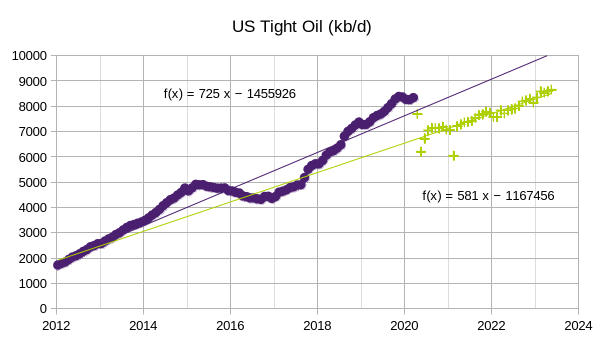

The chart above shows the most recent EIA tight oil estimate (spreadsheet at this link) with data from Jan 2012 to May 2023. Two trend lines are presented with April 2020 to May 2023 having an annual rate of increase of 581 kb/d and the earlier Jan 2012 to March 2020 period having an annual rate of increase at 725 kb/d on average.

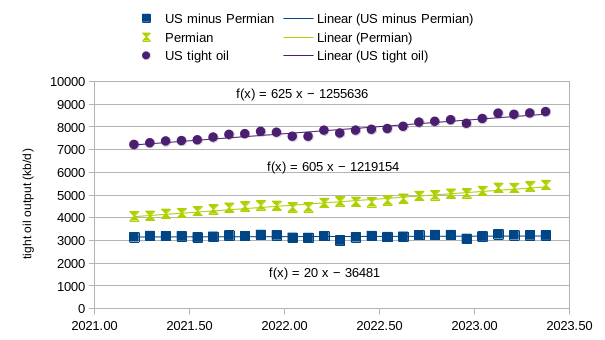

For the more recent March 2021 to May 2023 period, the US tight oil trend has an annual increase of 625 kb/d, the Permian has an annual rate of increase of 605 kb/d and the rest of US tight oil (everything except the Permian basin) increased at an annual rate of 20 kb/d over the past 27 months. In the future, I expect Permian output will increase more slowly and expect the rest of US tight oil to be relatively flat over the next 5 to 7 years.

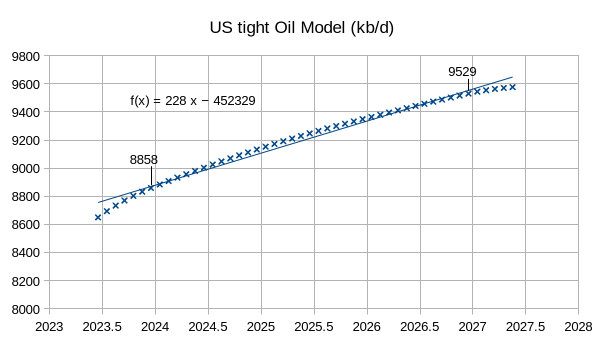

The chart above presents my tight oil scenario with monthly data from June 2023 to May 2027 with a trendline. The annual rate of increase is 228 kb/d over this period, quite a bit slower than the rate of increase over the previous 27 months (or the previous 37 months). The output levels for December 2023 and December 2026 are shown on the chart.

The chart above presents the revised US tight oil and Permian tight oil scenarios, the US tight oil less Permian scenario is unchanged from last month. The US tight oil model peaks in September 2027 at a centered 12-month average of 9578 kb/d and the Permian model peaks in December 2027 at a centered 12-month average peak of 6358 kb/d.

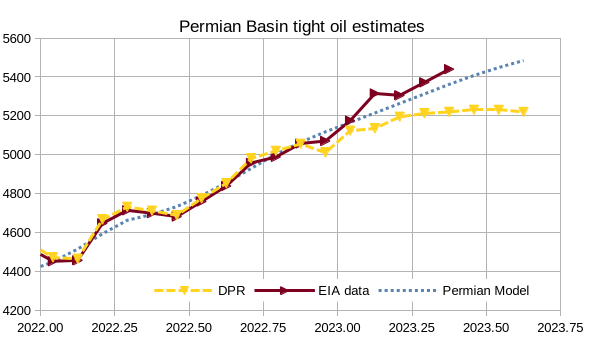

The chart above compares the EIA’s official tight oil estimate (labelled EIA data) with the recent DPR estimate for the Permian basin and my Permian Model. To compare the DPR with the tight oil estimate, I found the average of the difference between the two for the June 2020 to October 2022 period which was 545 kb/d. I had checked the DPR against state data from Texas and New Mexico and the match was good over this period, after that incomplete state data led to the DPR being higher than the state estimates after October 2022. The DPR estimate shown on the chart subtracts 545 kb/d from the DPR estimate to remove the conventional oil from the Permian region that is included in the DPR estimate. The match between the DPR estimate and the EIA data is quite good through November 2022, by May 2023 the DPR estimate falls to 220 kb/d below the EIA’s tight oil estimate. My model also falls below the EIA estimate in May by 83 kb/d. For August 2022, the DPR estimate is 265 kb/d below my Permian model (which was too low in May), it seems possible that the DPR estimate for the Permian basin is too low from Feb 2023 to August 2023.

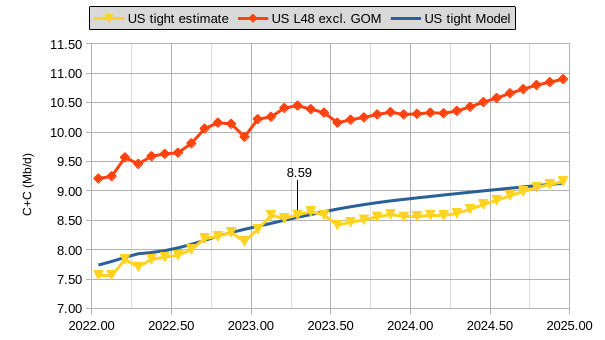

The chart above uses a similar methodology to what was used previously for the Permian Basin with the DPR and EIA estimate, but uses the US tight oil estimate and the US lower 48 output excluding the Gulf of Mexico (US L48 excl GOM) estimate from the EIA’s STEO. The difference between these is about 1.73 Mb/d on average from August 2021 to July 2022 and this was subtracted from the US L48 excl GOM estimate to arrive at a US tight oil estimate from May 2023 to December 2024. The data on the chart from Jan 2022 to April 2023 is the official EIA tight oil estimate up to the 8.59 Mb/d called out on the chart, after this the data is the estimate I have outlined with each US tight estimate data point 1.73 Mb/d less than the corresponding US L48 excl GOM data point. My model does not match this estimate very well from July 2023 to August 2024 with the model being as much as 350 kb/d too high in March 2024. In August 2023, the model is 262 kb/d higher than the tight oil estimate which might be coincidence, but the Permian model was about 265 kb/d higher than the DPR estimate for August 2022. It could be that the STEO is using the DPR for part of its modelling for US output. I will fix my models as presented this month for 6 months to see how they play out over time. We might find that the EIA estimates will be adjusted over time and it would be interesting to see how well the models do.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha Editors.

Read the full article here