Artificial intelligence (AI) has garnered significant public attention in recent months, especially since the groundbreaking launch of the large language model, ChatGPT. Some of that newfound attention has centered around the notion of an impending “AI apocalypse.” While these ideas emerged from online communities peddling fear-mongering theories unbacked by substantive evidence, the ideas are increasingly going mainstream, supported by journalists and moneyed interests intent on influencing policy debates. In an attempt to lend credibility to their narratives, there is now burgeoning interest in academic research that aligns with the doomsayers’ predictions.

While academic research is a cornerstone of intellectual progress, there is a balancing act to be struck so that it doesn’t morph into a tool that politicizes science in order to advance a preset policy agenda. We have already seen these dynamics play out extensively in the realm of climate change economics, and there is now increased danger that AI economics research will follow a similar path.

A case in point is a recent paper penned by the esteemed MIT economist Daron Acemoglu along with MIT grad student Todd Lensman. Acemoglu, a highly-influential figure in economics, has contributed considerably to the field with his scholarship. However, the same cannot be said for his latest paper, which presents a model that attempts to explain how transformative technologies like generative AI augment “social welfare,” and subsequently how regulation could improve the situation.

Acemoglu’s model hinges on the “Ramsey economic growth” framework, a modelling approach that has, regrettably, embedded itself deeply in the field of economics. The model wields considerable influence, underpinning cost-benefit analysis and also utilized extensively in climate change economics. For example, it is used in determining the “social cost of carbon”— a concept that aims to capture the welfare impacts of CO2 emissions.

Born out of the intellectual pursuits of mathematician Frank Ramsey in the 1920s, the original model was later picked up and amended by economists like Tjalling Koopmans and Kenneth Arrow in the mid-20th century. Despite the undeniable academic stature of these economists, the Ramsey framework stands on shaky scientific ground.

Instead of simply outlining how economic growth might be affected by technology, investment, and population changes, the Ramsey framework also incorporates a dubious “social welfare function” that translates these inputs’ impacts into a measure of “wellbeing,” something that isn’t observable to any analyst. The model thus blurs the line between positive impacts (what happens) and normative ones (what the analyst thinks is good or bad).

The misleading character of the Ramsey framework makes it all too amenable to misuse, and this is precisely what has happened in the area of climate economics. The Ramsey framework was taken up and used to model the “welfare cost” of climate change on a global scale. These models are often presented as if they are scientific, but they rely heavily on hidden ethical assumptions. Scientific questions—such as how CO2 impacts temperature or growth—are thrown together with policy questions—such as how much weight these impacts should carry in decision making. The end result is a complex, pseudo-scientific mess that looks like science—because it incorporates a plethora of data, equations, and technical academic research—but really is little more than doctrinaire policy advocacy.

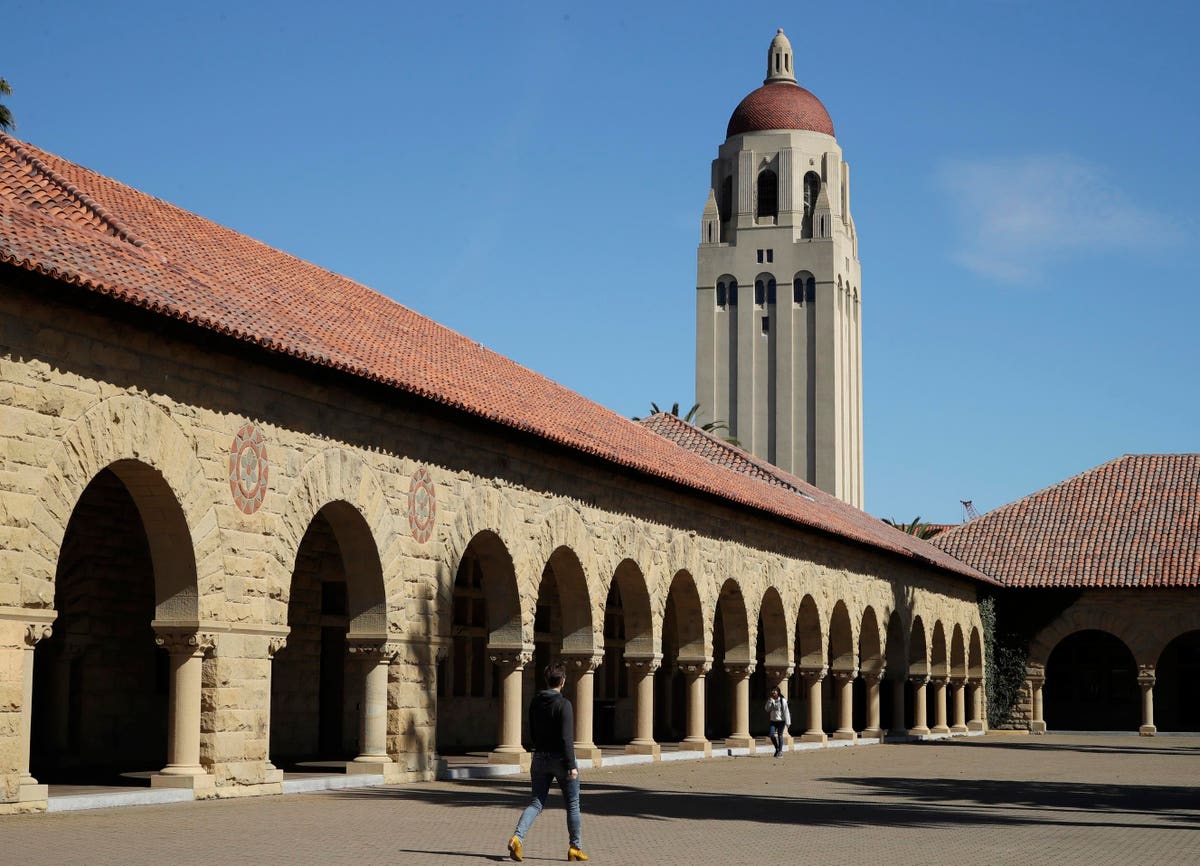

Consider that this week Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne announced his resignation following an ethics scandal that involved the manipulation of data and images in his scientific research. There is much to be gained from scientific deception, including not just money but also powerful positions in America’s most prestigious universities and companies. Scientists need not be intentionally deceptive either, if the mainstream methods of their field have become corrupted.

Acemoglu, in collaboration with another MIT colleague, Simon Johnson, has penned a polemical new anti-technology book ironically titled “Power and Progress.” In it, Acemoglu and Johnson pontificate against what they see as technology’s history of unfair consequences for workers and the poor. We should perhaps not be surprised then that Acemoglu was drawn to the Ramsey model, with its emphasis on placing ideological conclusions ahead of scientific exploration.

If AI economics gets off on the wrong foot, misled by unfounded fear and pseudoscience, it will soon turn into little more than a branch of medieval alchemy. Before this intellectual weed takes root, it is imperative economists stamp out these emerging tendencies. The field of AI governance is desperately in need of robust, scientific thinking to guide policy. Economists can play a role in making this a reality, but only if they leave their ideological baggage at the door.

Read the full article here