The bigger they come, the harder they fall—just not yet.

We’re speaking, of course, of Big Tech, whose artificial intelligence-fueled run has prompted concern that

Apple

(ticker: AAPL),

Microsoft

(MSFT),

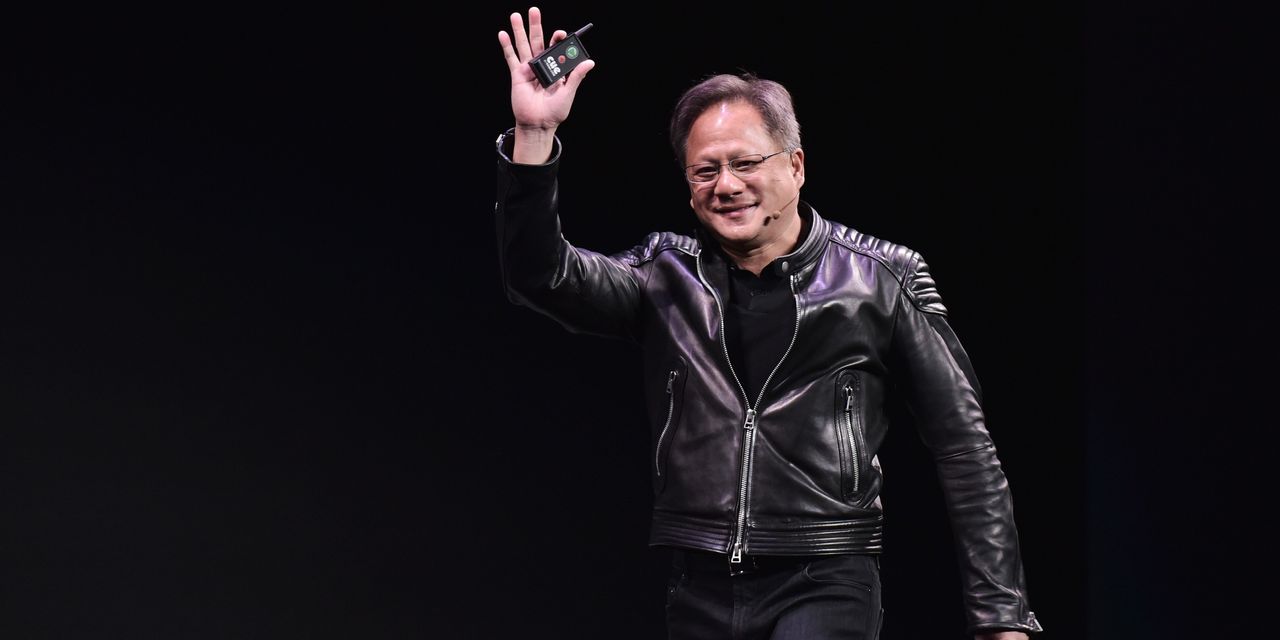

Nvidia

(NVDA), and the rest have entered a massive bubble that is going to end, well, badly. The Big Seven, as those stocks combined with

Amazon.com

(AMZN),

Alphabet

(GOOGL),

Meta Platforms

(META), and

Tesla

(TSLA) are known, have gotten so big that Nasdaq decided it had no choice but to rebalance the

Nasdaq 100 index.

It seems that there’s an obscure rule on the books that requires such a reweighting when all the stocks that make up 4.5% of the portfolio or more combine to make up 48% or more of the index.

That announcement took a little wind out of Big Tech’s sails this past Monday, when the Nasdaq 100 rose less than 0.11%, underperforming both the

Dow Jones Industrial Average

and the

S&P 500,

as six of the Big Seven fell. The moves, though, turned out to be a one-day blip. By Thursday, the Nasdaq 100 had gained 3.6% and outperformed both the S&P and the Dow.

Still, size can be an impediment to performance. Indexes will rebalance, forcing investors benchmarked to them to sell. Active fund managers, too, will have to sell the stock if they have position limits in place, which many of them do. And the math works against the Big Seven as well: It’s much harder for a stock to double when it has to go from $3 trillion to $6 trillion, as Apple now must do, than from $1.5 trillion to $3 trillion.

But a bubble? Hardly. Yes, the Nasdaq has gained 42% so far this year, more than the index’s 29% rise to start 1999, the year the dot-com bubble inflated to massive size. Yet the moves couldn’t be any more different when looking at what came before them: While the Nasdaq has gained just 4.2% over the past two years, the index surged 134% over the two years ended July 13, 1999.

“With all due respect, we think the 1999 analog ignores the outlier performance leading up to and through 1999,” writes Seaport Global strategist Victor Cossel. “While we know 2022 was a painful year for assets, we feel many have dismissed it or written it off despite significant drawdowns in both stocks and bonds as they repriced for economic & fiscal slowing and monetary tightening.”

Even on a valuation level, the Nasdaq 100 doesn’t look quite so bubblicious. The Nasdaq, he points out, trades at a cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio of 46 times, well below the 113 times it reached in 2000, according to Citigroup data, or the 83 times reached by Japan in 1990. Valuations are still high, though, high enough that we’d typically want to recommend paring back.

That might not be the right move. Citigroup strategist Scott Chronert notes that mutual fund managers have been struggling to keep up with the index, and he sees what he describes as “early signs of performance chasing.” Futures positioning has also lightened up in recent weeks, suggesting that there’s more room for buying.

“All told, we see merit in holding existing mega cap/growth cluster positions and would view weakness in the group as a buying opportunity,” he writes.

But that doesn’t mean it’s all that should be bought. Consider the case for

Alibaba Group Holding

(BABA), which has a market cap of just $243 billion, a fraction of Apple’s, despite a faster growth clip. As the Bear Traps Report’s Larry McDonald puts it: “Right now, nearly 13 Alibaba’s fit in one Apple market cap. In our view, BABA widely outperforms overly-crowded Apple in the coming months.”

And perhaps even longer. Wolfe Research strategist Chris Senyek values Alibaba on the sum of its parts, with the Taobao Tmall business fetching 12 times 2024 earnings, for a value of $85, and the remaining businesses worth about $60. That would put the stock at $145, or up 50% from Thursday’s closing price of $96.61.

It’s not quite a double, but it’s a start.

Write to Ben Levisohn at [email protected]

Read the full article here