Dancing on the Razor’s Edge

Imagine that your parents are talking about splitting up. Now imagine that your parents are the two most powerful people in the world and, between them, control the most attractive opportunities to advance in your career. Now imagine that your parents insist that all their friends and family pick sides and definitively break off relations with the enemy camp.

Welcome to life as an ambitious global corporation as tensions mount between the U.S. and China. Whether it is a strict “decoupling” or more selective “de-risking,” both nations keep piling new restrictions on trade in technology, cross-border investment, and market access that makes it increasingly challenging to maintain a position of friendly neutrality.

This poses a quandary for CEOs of multinational corporations. If you are not a player in the Chinese market, you may soon be relegated to second-class status. But if executives appear overly sympathetic or supportive to China, they may find their companies subject to sanctions or political shaming back in America. This situation has placed the CEOs of some of the best companies in the world on a razor’s edge, and it is instructive to see how they have managed to artfully dance across it – for now.

Riding the AI Rocketship

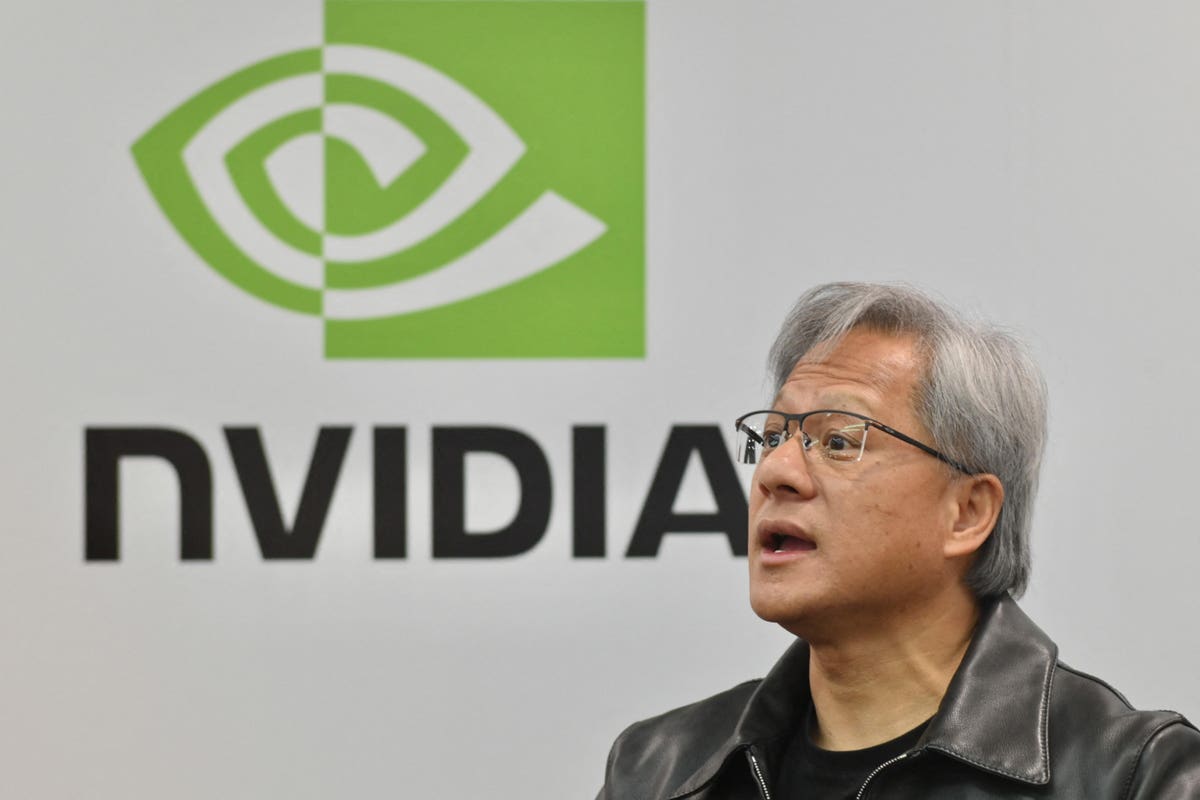

Born in Taiwan, Nvidia’s CEO Jen-Hsun “Jensen” Huang is acutely aware of the stakes of the battle for AI supremacy between China and the United States. He has built Nvidia into the world’s most valuable semiconductor company by making astute long-term bets on the future of semiconductors required to power AI. In May, Nvidia (NASDAQ

NDAQ

In 2017, the Chinese government announced a strategy to become the world leader in AI technology by the year 2030. Their plan included inventing new chips for neural networks that could displace Nvidia as the dominant supplier of GPUs at the heart of supercomputers and AI data centers. To put it mildly, the plan flopped. By 2022, Nvidia’s chips powered most of China’s AI research labs, and its customer list included top industry players like Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and TikTok owner ByteDance. The Chinese government-backed challenger, Cambricon, has yet to launch an AI GPU and recently reported widening losses.

Then in August of 2022, the U.S. Commerce Department banned selling Nvidia’s most advanced chips used in AI and supercomputing applications in China. The government claimed that these advanced GPUs had the potential for dual use in military and surveillance applications, including autonomous warfare, developing nuclear weapons and hypersonic missiles, and AI surveillance tools. Nvidia’s stock dropped. China protested the “tech blockade.” But by November 2022, Nvidia announced a throttled-down version of its A100 GPU that could be sold in the China market. And at the end of May, Nvidia announced a massive increase in its sales forecast driven by AI data center demand that erased any concerns about the China market and sent the stock soaring.

While Wall Street might have been ready to forget about the China sanctions, it was clearly still gnawing on Jensen Huang’s mind. In an interview with the Financial Times, he mused that if China “can’t buy it from the United States, they’ll just build it themselves. So the U.S. has to be careful.” He called China an irreplaceable market for the U.S. tech industry. If it were to disappear, there would be insufficient demand to support Biden’s goal of rebuilding onshore semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S.

At the Computex Conference in Taipei, he said that the regulations left Nvidia with “our hands tied behind our back.”

After publicly questioning the wisdom of U.S. semiconductor policies toward China, Huang fell silent. Rather than flying on from Taipei to Mainland China to visit with customers, he flew home to Silicon Valley without explanation.

Are Huang’s anxieties about potential local challengers from China justified?

For now, Nvidia’s dominance of GPUs in AI data centers appears unchallenged. Beyond its hardware, the company’s proprietary software CUDA (compute unified development architecture) has become the standard for AI programming imposing high switching costs on users. But having disrupted the semiconductor industry multiple times with contrarian bets, Huang has a finely honed sense of how fast competitive dynamics can turn on their head.

An Intertwined U.S.-China Economic Relationship

Few CEOs have shown as much unbridled enthusiasm for China as Elon Musk.

In July 2020, he favorably compared his employees’ attitudes at Tesla’s (NASDAQ:TSLA) Shanghai Gigafactory to their colleagues in the U.S., saying, “China rocks, in my opinion. The energy in China is great. People there – there’s like a lot of smart, hard-working people…whereas I see in the United States increasingly much more complacency and entitlement, especially in places like the Bay Area, and L.A. and New York.”

In 2022, China contributed over half of Tesla’s global sales, with 711,000 out of the 1.3 million vehicles produced in the Shanghai factory. Production costs are about 20% lower in China, making it a valuable and profitable base for exports to Southeast Asia and other markets.

But Tesla’s success in convincing Chinese consumers that EVs can be both high quality and cool has inspired a host of competitors, which have whittled away at its market share as domestic production exploded. While sales of Teslas were up by 40% in 2022, shipments by its Chinese rival BYD rocketed by 211% to 1.8 million.

Asked who his closest global rival was in early 2023, Musk replied that the Chinese EV manufacturers “work the hardest and they work the smartest. And so, we guess there is probably some company out of China as the most likely to be second to Tesla.”

In fact, if you count hybrids, BYD is already the number one player in EVs globally. The pace of new product introductions in China is dizzying, with over 100 new EV models in 2022 and another 150 expected in 2023. Tesla’s brand is associated with innovation in the U.S. and Europe; in China, they risk seeming dated without a refresh since the launch of the Model Y in 2021. Tesla didn’t even show up to the Shanghai Auto Show this past April.

To remain relevant, Tesla planned to open a new factory outside Shanghai to produce another 450,000 cars annually, including a new lower-cost model to compete with domestic rivals. But the Chinese government has been slow to approve the new plant, concerned with industry overcapacity and a price war that Tesla initiated.

In early June, Musk flew to China as part of a charm offensive to meet with government officials and critical suppliers. During a meeting with China’s foreign minister, he stated, “The interests of the United States and China are intertwined, like conjoined twins, who are inseparable from each other,” according to a government transcript.

The Chinese government and Musk’s 2.2 million followers on the Weibo social media app have embraced him as a model Western executive. But the approvals for the new factory have yet to be issued. And as Elon Musk sees how fast Chinese EVs have gobbled up the domestic market, he must be thinking about how he will compete as Chinese brands begin to flood Europe and other global markets. Will he be able to move at China speed and compete at a China price? It’s very much an open question.

Chasing an Elusive Prize

China’s $60 trillion financial sector has remained a tantalizing prize for global banks, and few have pursued the opportunity with more vigor than JP Morgan (NYSE:JPM).

JP Morgan has been in China for over 100 years. CEO

Jamie Dimon was forced to issue an abrupt apology in 2021 when he joked that the bank might even outlast the Chinese Communist Party. The bank has a securities firm, mutual funds, and futures business in mainland China. And in 2023, JP Morgan received approval to acquire 100% of its asset management business in China with $27 billion in assets.

So, a lot was at stake when Dimon traveled to Shanghai at the end of May for the bank’s Global China Summit. Would he be able to avoid offending those listening carefully to his remarks in both Washington and Beijing?

In an interview with Bloomberg Television, he emphasized JP Morgan’s long-term commitment to a presence in China.

“When we do business in a country, and we do business in 100 countries around the world, we are there for the citizens of the country,” he said. “We’re there hopefully through good times and bad times. We tend not to leave, other than if there’s war or civil war. And so, we’re not predicting any of that here.”

He also provided gentle constructive advice to China’s policymakers, “If you have more uncertainty, somewhat caused by the Chinese government,it’s going to not just change foreign direct investment. It’s going to change the people here, their own confidence to invest.”

At the conference, he called for “real engagement” between the U.S. and China, focusing on de-risking rather than decoupling the two economies. “You’re not going to fix these things if you are just sitting across the Pacific yelling at each other,” he noted.

Despite these efforts, JP Morgan and other American investment banks have seen their share of IPO underwriting on the mainland’s A-share market continue to slip. So far this year proceeds from IPOs in China have been four times the U.S. But U.S. underwriters have participated in precisely zero of these new equity offerings.

McKinsey & Company recently estimated that China’s asset management business would double from $20 trillion to $40.4 trillion by 2030. Will Western firms be able to capture more than a minuscule slice of this market? Or will it remain an elusive dream? At the very least, Dimon seems determined that JP Morgan remains in the ring to find out.

Bridging the Divide

As the U.S. seeks to reset the terms of its relationship with China, each of these CEOs has sought to point out the potential costs of spiraling confrontation. While the CEOs certainly have strong economic motivations to encourage cooperation, they also have a detailed understanding of the connective tissues that bind the two “conjoined twins.” Severing those tissues entirely could severely limit the growth potential and reduce the prosperity of both the U.S. and China while increasing the risk of armed conflict.

The recent trip by Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to Beijing, the first by a U.S. Secretary of State in five years, is an encouraging start. Given the vast differences between the policies and public opinion in each country, resuming constructive discussions will be no easy feat. But such talks offer the only prospect of dismounting from the razor’s edge in one piece.

Read the full article here