On July 6, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration granted full approval to Biogen (NASDAQ:BIIB) and Eisai’s (OTCPK:ESALF, OTCPK:ESAIY) anti-amyloid antibody drug Leqembi. For some physicians, advocates of the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer’s organizations, investors, caregivers, and loved ones it was a day to celebrate. But others remain deeply skeptical about the efficacy and safety of the drug.

The initial Wall Street reaction to the news was lukewarm at best. Biogen’s stock dropped almost ten points or roughly 3.5%. Leqembi’s full approval has been expected for quite some time. Some analysts see this as a temporary blip that will right itself over the long term once production is ramped up, more infusion centers are opened up, and a non-infusion method of administering the drug is developed. However, the strongly worded FDA warning label regarding the potential for brain swelling (edema) and brain bleeds (hemorrhaging) is something that is likely to remain. And later in this article, I will present a series of scenarios that could dampen Biogen’s profits and cause some investors to sell the stock.

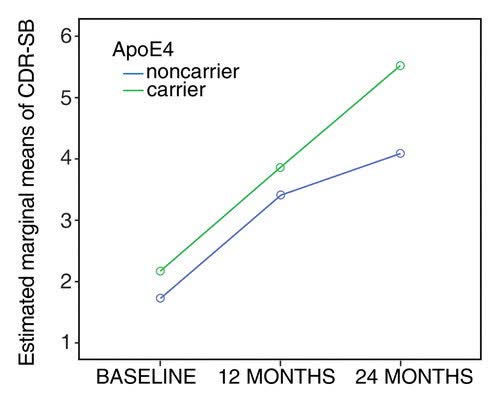

Before doing so, I want to briefly return to and refine my observations from a previous article regarding the impact of Leqembi on ApoE4 carriers and non-carriers. The rate of decline between carriers and non-carriers begins to diverge around a CDR-SB score of about 3.2 which is both indicative of very mild Alzheimer’s disease and quite close to the mean baseline for participants in lecanemab’s (now Leqembi) phase 3 clinical trial.

Progression rates of ApoE4 carriers versus non-carriers (Original Research Radiology)

At 18 months from a baseline of 3.2, non-carriers would decline to about 4.2 points whereas carriers would decline to about 5.5 points. Biogen and Eisai though combined carriers and non-carriers into one placebo group. In essence, they landed upon a decline at 18 months (4.83 points) that fits between the blue non-carrier line and the green non-carrier line. Further separating between the decline in those with two copies of the ApoE4 gene and those with one copy of the gene becomes somewhat more complicated. Carriers with two copies of the gene progress somewhat more rapidly than those with one copy of the gene (study). Anti-amyloid drugs may have at least a slightly greater impact on those with two copies of the gene than on those with one copy of the gene (clinical trial). Taking into account the variables discussed above, it is possible to provide a more accurate estimate of the impact of Leqembi on ApoE4 homozygotes (two copies of the gene), ApoE4 heterozygotes (one copy of the gene), and non-carriers than that provided by Biogen and Eisai.

Biogen and Eisai’s Numbers

- Non-carriers 4.83-.75=4.05

- Heterozygote carriers: 4.83-.5=4.33

- Homozygote carriers: 4.83+.28=5.11

More Accurate Numbers

- Non-Carriers 4.2-.15=4.05

- Heterozygote carriers 4.93-.6=4.33

- Homozygote carriers 5.81-.7=5.11

The upshot of this is that a twice monthly intravenously administered drug that costs $26,500 is being given to non-carriers to produce about .15 slower decline at eighteen months. Biogen and Eisai knew that their drug has almost no impact on non-carriers from its phase 2 trial on lecanemab. The FDA more or less knew it from the aducanumab phase 3 clinical trial results (another Biogen and Eisai anti-amyloid antibody drug) and at least some researchers in the Alzheimer’s organizations pushing for full FDA approval and full Medicare coverage of Leqembi likely knew it, as well. Perhaps to understate it this is troubling.

The arguments made on behalf of Leqembi are that it produced clinically significant results and that unlike acetylcholinesterase drugs which produce similar results at 18 months, it alters the course of the disease. On behalf of the first argument, proponents claim that a .5 slower rate of decline at 18 months is clinically significant which is convenient given the numbers that Biogen and Eisai provided. Others put the threshold for a clinically significant outcome considerably higher than that, but even by the most liberal definitions, Leqembi produces barely clinically significant results in ApoE4 carriers.

The second argument is neither provable nor unprovable at this point. However, since amyloid is only a secondary cause of Alzheimer’s in ApoE4 carriers its removal is not likely to fundamentally alter the course of the disease.

The future pitfalls for Biogen fall into the following two categories.

Efficacy and Safety Concerns

There are a number of physicians who will not prescribe Leqembi due to safety and/or efficacy concerns. And there are a number of caregivers or patients who will not take it due to safety concerns and due to the burdensome infusions. Some may not be able to take it if they do not have insurance or if their insurance provider (if not on Medicare) does not cover it.

Medicare seems primarily interested in monitoring for adverse side effects, but it may be that the lack of efficacy in non-carriers emerges as well, especially if annual testing is done.

The number of deaths resulting from the usage of Leqembi could also be an issue. The FDA has approved a number of drugs that cause fatalities, and only rarely rescinds approval. However, if the deaths resulting from Leqembi become substantial, Medicare could pull coverage from the drug.

The irony for Leqembi is that for non-carriers it comes with few risks but has no efficacy while for carriers it comes with marginal efficacy but with potentially catastrophic side effects.

The Competition

The failure of Biogen and Eisai to gain full approval for aducanumab/Aduhelm cost the companies a year or so of unimpeded profits. Now other companies with anti-amyloid drugs are much closer to competing with Biogen and Eisai than they were before. Closest of all is Eli Lilly with donanemab. But there are several others as well. Most promising (or most threatening depending on how one looks at it) is Alzheon’s ALZ801. Alzheon has acknowledged that its drug only helps ApoE4 carriers, but its advantage over anti-amyloid antibody drugs is that by inhibiting the buildup of amyloid rather than removing amyloid it does not cause brain swelling and brain bleeds. There are a number of other companies with largely non-amyloid related drugs waiting in the wings as well. Their argument will be if our drug is safer and at least as effective as Leqembi it should be approved as well. With few exceptions, any drug that even tangentially targets the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease is going to be more effective in non-carriers than Leqembi. Alzheimer’s disease is a several billion dollar market, but if several competitors enter into that market then the profits begin to be split as well.

Concluding Reflections

For almost a decade, Biogen’s stock value has been largely defined by its efforts against Alzheimer’s disease. Ironically, the FDA’s approval of Leqembi may have finally changed this. It could be that once the profits from Leqembi begin to come in, Biogen will once again go up on Alzheimer’s news or once one or more of the pitfalls outlined in this article occurs, Biogen will go down on Alzheimer’s news. But the speculation as to whether one or more of Biogen and Eisai’s drugs will be approved for Alzheimer’s disease is over. Biogen will now have to rely more heavily on its current and future drugs, which at this point at least may not work in the company’s favor. I am slightly pessimistic about Biogen’s future stock price, but not enough to recommend selling it at this point.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here