Dear subscribers,

In many countries/cultures, including the one I currently live in, it’s a bit taboo to talk about money – specifically how much you make, how you made it “there”, and how you arrange/invest your money to make sure you stay there. It’s a very ethereal set of questions, almost alchemy unless you’re already “in the group” – meaning unless you’re already one of the people there.

It’s true even for me, I don’t often talk with colleagues and acquaintances, certainly not strangers, about how I made my money, how I invest it, or what has made me rich. That sort of discussion is saved for a select number of people – friends, family, and close business partners I trust.

As well as here – where I write mostly from anonymity.

I do firmly believe, however, that we’re doing people a disservice by not talking about this more than we are.

So periodically, I try to write an article where I touch upon this subject. It’s been over 16 months since the last article where I spoke about this.

So it’s time for a reminder and an update.

How to Become a Millionaire – Three Simple Steps

In a previous article, I shared some light on three simple strategies I used since my early twenties to amass the capital needed for investing in order to see it grow to the million/s.

In essence, these steps are as follows:

1. Economy

Make sure that you put yourself in the right financial circumstances to where you’re able to spend below your means and save above your circumstances. By oversaving capital and investing it, you put yourself in a position for compound growth investing.

Every single self-made millionaire I have ever met has had this trait in common. We don’t overspend on luxury items unless we can afford them simply from the interest on our principal. We drive conservative vehicles and live in houses either average or below what we could afford – at least until we could afford cars and houses only with the interest rate income from our principal.

Realize that any hobby, interest, or non-work-related activity you have that consumes over 10-30% of your savings has the realistic potential of setting you back several years – that’s years, not months or weeks.

What you’re doing when you spend discretionary capital is that you’re applying the reverse of compound growth to your portfolio, compared to what you could have if you invested it better.

Remember – the very hardest thing in the journey to your million is actually getting the ball rolling. Once you get that snowball rolling – get to around $200-$500k, things get a lot easier. But looking back, nothing for me was harder than my first $100,000. It took years.

What I will say is that unless you’re able to oversave and underspend, and if you don’t come from riches or happen to win the lottery, I can almost guarantee that you won’t reach the goal of a millionaire. It becomes too hard, to put it simply – and it has very little to do with your job. I’ve met people with very average jobs that have become millionaires, and company leaders that decided to live very extravagant lives that did not become actually “wealthy” despite their jobs and status. At one time, when I sat with a potential client for asset management, I was surprised how little liquid/investable capital he actually had, when everything was stripped away.

What you do when you want to become wealthy isn’t necessarily growing your income – it’s growing your net worth. And those are two different things, believe it or not.

2. Diversification

In diversification, we talk about making sure you’re not overexposed to one asset or sector. With someone that has as much in the market as I have, diversification is key to making sure I stay safe. I don’t have any holdings higher than around 5% unless the holding happens to be in a growth streak. Most sectors are around 5-12% of my total portfolio value – with only 2 above 12%, and none above 16%.

What exactly does portfolio and investment diversification do?

It reduces the risk, by investing in securities across different industries, categories, and geographical regions.

You reduce unsystematic risk from your investments, which you have if you were to invest say, 50% in energy or 40% in REITs. If those sectors end up turning, you’re going down with them. By diversifying you reduce that unsystematic risk.

You would then further diversify and reduce unsystematic risk by perhaps investing in telecommunications, foods, healthcare, and so on.

By doing so, when there is a downturn in one sector, your other portfolio sectors hold things afloat – at least in theory, and according to people working with data – statisticians call this a correlation, which you’ve probably heard, but maybe not entirely understood.

The major difference in my current portfolio composition since the last time I wrote an article like this – aside from my core portfolio now being above $2M, is having a double-digit 13% cash position. I have this due to my investment strategy of using cash-secured puts, which I use to get an 8-12% annualized yield on that cash, and the buying power associated with it. This is the diversification that I’ve more clearly added to my approach since my last article, and it’s been working out well for me.

I want to make it clear, that compared to some, I don’t consider myself super-well diversified. I could go into Eastern Europe. More into Asia, and buy more Japan or Australia. Perhaps even Indonesia. There are plenty of avenues that could offer positive diversification here.

The net result of diversification, including my own diversification, is a lower overall beta for my portfolio when considered at constant FX. This was the goal when adding options as well. I’ve been able to garner an average of 11.2% annualized yield on the cash I have, as well as a variable amount of buying power that I put “at risk” depending on how attractively priced cash-secured put options that I am able to find.

Diversification, therefore, is crucial. How diversified you’ll want to be, that’s another thing entirely. The number of stocks/investments is something people often ask about. I can freely say that my core portfolio nowadays tends to consist of 40-50 stocks, and my usual target is about 1-3% per investment, with some being as much as 5%, and many being below 1.5%.

But actually having diversification and a strategy about how you invest, that’s crucial.

There is a downside to diversification. You won’t see me argue with that. The more you diversify, the more you lower your own outperformance potential. You also have higher investments, with higher brokerage fees, transaction fees, etc. In fact, my fees and brokerage costs are significantly higher these days than I had years ago. I would say on average now I pay around $500 per quarter in various fees and transactions. However, much of that is due to options tradings – I usually do around 150-200 options trades per quarters these days. This combined with my more “active management”, allowing me to retain a large cash position while still making a good return off that cash and buying power with secured puts, that’s added diversification to my approach. As an example, in 1Q23, I made a 20.5% YoC off my actual cash, and around 9.5% of my total buying power – but less than 4% of these options were actually assigned.

Understanding your diversification goals and strategies is important. I’ve told colleagues and friends that unless they have, say a certain amount of capital, they shouldn’t even consider starting to trade options in the first place. I give you the same guidance here.

Something like options trading requires access to capital that might be beyond many investors – and if you don’t have it, don’t force yourself into that specific mold or strategy.

Use a strategy and a diversification that suits your objectives and circumstances.

For years, all I did was reinvest in dividend-paying stocks, and I don’t regret that. It brought me to where I am today. Years ago, I would have considered paying hundreds of dollars in fees per quarter absolutely criminal. Today, it really doesn’t matter to me, because I look at it as a percentage of the income and circumstances that result from that strategy.

Remember, though when it comes to diversification and what you should be doing.

I want you to remember this. Jot it down, etch it into your mind.

No analyst, no matter what they say or how good they are, can ever 100% guarantee that an investment will not result in a loss of capital for you.

No one, and ever. Anyone who claims the opposite or even indicates that they can somehow forecast what will happen 100% is essentially claiming the ability of clairvoyance.

This is why diversification is a solid part of any strategy that, in my mind, is worth it’s salt.

Now, the degree of diversification you want to have, that’s an entirely different thing. And this will depend on your circumstances.

3. Keep It Very Simple, And Be Patient

Despite what I said above about options and the like, I view myself as keeping things extremely simple. Options trading for me is an addition that’s 100% based on my knowledge of quality companies. Beyond that, I still follow the same tenets that I’ve done for years.

I buy undervalued and underappreciated companies that I believe, based on fundamentals, trends, historicals, and projections, have the ability to outperform.

A ratio of 100% is impossible. No one has 100% But over time, i’ve found my “batting average” to be well above where the average investor seems to be.

So what’s the differentiating factor for me when I look at others?

I can’t say for certain, of course, but what I would boil it down to is simplicity and patience.

Many investors seem to have a tendency to panic and overreact both during upswings and downswings. I make it a point not to allow emotional reactions to dictate my trading patterns or my targets. Even if a company like Lincoln National (LNC) continues to drop, I don’t change my long-term target for the company. I still maintain that the fully realistic long-term RoR for this investment is over 500% potentially.

Unless something fundamental in a company changes, I very rarely shift my stance.

I also never go into smaller, overly complex investments if the same result or the same RoR can be achieved by doing things simply. Don’t overcomplicate things. Don’t do things just for the sake of doing them. In my case, don’t spend 30 minutes explaining something that could be explained in 3.

If I can buy 5%-yielding Realty Income (O) at a double-digit upside, I won’t spend my time forecasting or allocating to a much smaller REIT at a similar upside and the same yield. I don’t diversify for the sake of diversification beyond a certain point and always retain simplicity, quality, and patience as my guiding qualities.

This sort of strategy is often espoused by legendary investors. Many newer investors and tech-focused newcomers to the market take an unfavorable view of Buffett and Munger, who are very clear that they don’t invest in things they don’t understand – such as tech.

Notice however that despite these things, Buffett and Munger are very sanguine about what they “lost” by not investing in tech stocks – that’s because despite what they may have lost, they’re still the most successful investors on the face of the planet.

Despite being quite well-versed in tech, my investments in tech are very limited – and will continue to be that way. I like things that I can touch, industries, and companies that produce more basic-level products. I like industrials, chemicals, metals, buildings, and materials – and I like the services and industries that make these businesses run – such as finance, insurance, and business service companies. I don’t like as much, businesses that operate strictly on a more ethereal software/service base.

I’m not saying they’re bad companies – but from what I’ve found, investors and analysts that try to sell or to convince about these companies spend a lot of time talking about ifs, potentials, and forecasts if a company hits a certain level or target.

The difference with the companies that I analyze and invest in is that they rely on historically proven data/trends with commodities or products that are unlikely to shift significantly in terms of use-case/usage. It’s not as exciting, because the higher degree of forecastability also means they’re unlikely to massively outperform – but it adds downside protection as well.

9 out of 10 investors I’ve spoken to need no more than a simple investment portfolio made up of 20-35 companies they understand and know well, and a 2-hour course on basic valuation techniques to know how things work, when to/if to sell or what to do when money comes in. They can then follow mentors or others who have the expertise and who have their best interests in mind.

Wrapping up

So, in essence – Economy, Diversification, and Simplification.

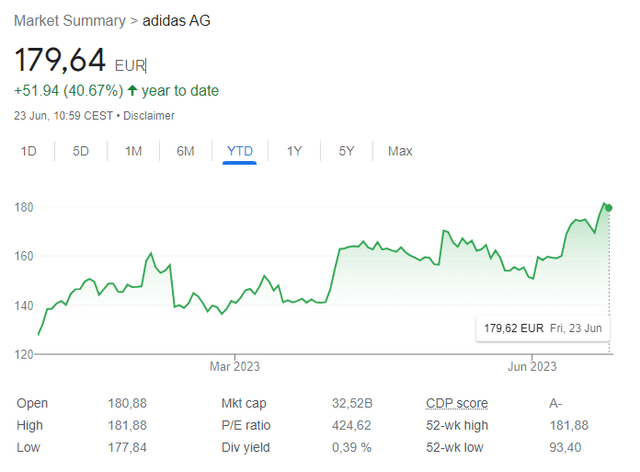

Patience would also go on that list because it’s a very underrated quality in today’s market. Take adidas (OTCQX:ADDYY) for instance. The last time I stated my thesis for the company was back in 2022 – and it’s “BUY”. I’m still at a “BUY” on Adidas, and I bought the company in the dip. While my position hasn’t fully realized its potential, the portion of shares I bought in the dip is now up almost 35%, which compared to the meager 4% the S&P Global has brought in the meantime is close to a 10x. Finding the bottom in that investment was a rough one – and as I said, my total position hasn’t yet realized where I want it to be.

However, I have no doubt that in time, the company will revert to where I see it in terms of valuation and premium, at which point I can harvest that outperformance.

If you’ve doubted Adidas, which some of you have, then I point to this YTD performance, which at least 30% of my portfolio position has enjoyed exposure to based on the cost basis.

Adidas share price (Google Finance)

Patience, dear readers. Once you’ve decided on a company, you should decide very carefully whether it’s time to exit that investment at a loss. I haven’t exited any investment at a loss in several years, and as time goes on, I tend to double down more and more on my core tenets and ignore what the short-term trends in the markets are telling me – because I believe them to usually be guided by that short-term sentiment.

Short-term sentiment does not matter to me.

Over the years, even here in SA, I’ve observed coldly and with calculation what these lessons have enabled me to do, different from other investors. By keeping it simple, by being economical, and by being diversified, I have never, not for years:

- Acted rashly in selling, or buying a stock/security

- Been convinced to buy what has turned out to be a fundamentally unsound or unprofitable business/company.

- Be panicked in a downturn – why should I be? I know that the companies I’m invested in are sound, regardless of what the market happens to think for the next 2 weeks or 8 months. I could not care less what the market thinks of them in the short term.

These trends are also what allows me to very quickly spot investments that do not fit my criteria. They also allow me to spot investors, analysts, or colleagues who act contrary to my own strategy. This is why I have an overall dearth of faith in much of the established analyst community. Allowing 3-24 month trends to completely dictate your investment mandate or strategy means that you’re always “outside” of the larger cycles.

And I believe the larger cycles, the 3-7 year ones, to be the ones where you can find the most profit. By that I mean you buy a company when it’s hated, then hold onto it for years if need be to see that reversion realized.

My approach means that I’m also never caught flat-footed or risk that I’m uncomfortable with overall. The biggest holding in my portfolio could go bankrupt overnight, and due to my diversification, I would still be up YoY in terms of dividends.

The downside – because every approach does have a downside – is that my RoR is, without any sort of doubt capped. I would say I’m capped at around 40-50% annualized in a superb bull market/reversal. That’s what I was able to make in the latest reversal. Outside of that sort of bull market, if I do my pickings right, maybe about 14-28% annually, with a strong tendency towards the lower end of that.

But you know what – that’s fine with me.

This isn’t an approach for people who want those 10,000% returns in 4-5 years. This doesn’t work for that goal, and if you want that sort of strategy, because you’re working from a very small portfolio and feel that you “need” that growth, then I’m not the guy to follow.

But to me, that isn’t conservative investing – that’s speculative gambling, and to engage in this would be disrespectful to the work and the money it took to get me where I am today. I also find this way of thinking to be compatible with almost every HNWI, VHNWI, or UHNWI that I’ve met or advised. And if they don’t share that view, that’s perfectly fine. There are many analysts and advisors that work more aggressively.

Me, I use the right lane, to equate this to driving. I drive the “speed limit”. I’ve observed key differences between Anglo-American and European investors and investment strategies and found myself tending towards the latter over the past few years.

I still employ approaches and strategies that favor conservative values and approaches. There is a reason why describing an approach as “American” doesn’t necessarily elicit a positive connotation in Germanic/central-European geographies, such as Switzerland, Germany, France, or BeNeLux. In fact, when I’ve spoken to people from the private banking/wealth management and asset management industry as well as clients, I’ve noted increased frustration due to what they view as the extremely short-term oriented vision of many anglo-saxon-oriented advisors and analysts, especially from Swiss, Eastern-European, and clients from France and Benelux.

In working, I’ve found that a mix of the two works extremely well – but that mix needs to be properly attuned, if you will, to the current market conditions.

Following these things is what has enabled me to be where I am today – and I hope this can be of help to you.

If you have questions, let me know!

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here