Ring-a-ring o’ roses,

Pockets stuffed with debtsies.

Nudge-wink, Hush-Hush!

We all fall down!

I discussed debt formation in my previous article “Macroeconomic Review: When Black Swans Circle” with total debt in the top ten global economies approaching and even exceeding 1000% of GDP in the case of Japan and the UK. The absurd low interest rates engineered by the global central banks through copious use of Quantitative Easing while overloading their own as well as the balance sheets of banks with central government debt has created a feeding frenzy in debt formation. The higher interest rates have yet to temper debt demand but have bankrupted the central banks (in spite of their denials and attempts to downplay the matter) and distressed the banking sector.

The debt problem is no longer a problem of debtors it is a problem for creditors. The old banking argument adjusted for inflation holds that if you borrow a million dollars then you will sleep badly but if the banker lends a trillion dollars, then it’s the banker who will not sleep. It is time for creditors to toss and turn when the repayment of the trillion-dollar loans becomes questionable.

Ask for a loan and your banker will look at:

- Your credit history, your record of having repaid your debt; and

- Your income to see if you can repay the debt; and

- The collateral that you offer to ensure repayment. No need to even look at this for governments. Governments do not offer collateral. Their power to tax is all the collateral creditors will ever see.

It is all about repayment. Fail any of the three tests and the bank will not lend you money. No use lending you money if you can’t repay the loan as well as pay the interest charged. In fact, the very first sign of a debtor in default is when the debtor can no longer meet its interest payment without increasing his borrowings. One can’t repay the capital borrowed unless interest is first paid. These rules are more stringently applied when we borrow money on a long-term loan to buy a house for example. All very obvious, yet the same faculties seem to have gone missing when creditors lend money to governments. Are any creditors still asking if governments have the ability to repay their debts?

The government’s income stream is its tax incomes and is published annually in its budget reports. It is relatively easy to establish whether a government can repay its debt or not. Governments generally maximize their tax income so what we see is the “best-case” incomes of governments.

We can apply the banking tests against government debt to see how they fare. Judging the credit history of governments requires a longer timeframe than that applied to individuals. This was eloquently argued by William Pitt, British parliamentarian, youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain and first prime minister of the United Kingdom when he suggested allocating money to a sinking fund with a specific aim to repay the burdensome debts of Great Britain.

“In the debate which ensued Mr. Pitt said: … If this million to be so applied is laid out with its growing interest, it will amount to a very large sum in a period that is not very long in the life of an individual, and but an hour in the existence of a great nation;”

National Debt. Report by the secretary and comptroller general of the proceedings of the Commissioners for the Reduction of the National Debt. From 1786 to 31st March 1890.

Government’s Credit History.

Debt and credit history in the context of governments indeed are generational. One or two generations will spend in excess and the next one or two will have to repay that excess spending. Pitt, a political character, and unusual personality in politics in his time had to contend with repaying the excessive debts of Great Britain accumulated during the American War. Pitt’s generation and the two after had to pay for the excesses of the previous generations. The report quoted deals with a period of just over 100 years.

It will be boring to construct credit histories for each of the ten top global economies on government timeframes so let’s just visit a few credit events in the financial histories of some of those countries. Their histories will show that they do default, but modern defaults usually are soft defaults, trickery, or bailouts rather than hard defaults.

A soft default is a default negotiated with creditors to restructure the debt usually from short term to long term, to impose partial default upon creditors by “agreement”, haircuts, and to set arbitrary interest rates upon such restructured debt. A recent example is that of Sri Lanka, though not a top ten economy, still shows the general “rules” followed in the case of a soft default. Repayment is replaced with “restructured” or “reformed”. None will use the word ‘default”.

The narrative is important. It is not the excess spending of government, its generous use of Central Bank money creation to fund that excess spending (the Sri Lanka Central Bank holds 62.4% of government treasuries) and the consequential hyperinflation it caused (peaked at 67.4% in September 2022) which resulted in a crisis but rather government acting to protect economic participants.

“This debt restructuring plan is essential for Sri Lanka to meet the target set by the IMF agreement to reduce debt from the current 128% of GDP to 95% of GDP by 2023,” State Minister of Finance Shehan Semasinghe told parliament.

“We are doing this while protecting banks, depositors and pensions.”

Sri Lanka parliament approves domestic debt restructuring plan, By Uditha Jayasinghe, Reuters, July 1, 2023

The Sri Lanka government can’t meet its debt reduction target through repayment to creditors, thus it will soft-default and force creditors to take a haircut of 30% on debt to reduce the government debt burden. Short-term bonds will be converted to long-term bonds after applying a haircut or holders can opt to pay a 30% tax rather than the standard 14% tax. The usual irony is that Pension Funds must take a haircut on debt and receive an imposed interest rates all in the name of protecting pensions. (Press Briefing, Presidential Media Centre on Domestic Debt Optimization (DDO))

The uneasy realities of a central government debt to GDP ratio of 118.6% as at Q1 2023 for the USA, and 100.1% for the UK as at the end of May 2023 (Net debt tops 100 per cent of GDP for first time since 1960s – Office for Budget Responsibility) prevails. This is not all of government’s debt, just central government debt. Not much different from Sri Lanka…

The UK had a history of hard defaults until the founding of the Bank of England in 1694 where after it was just soft defaults and bailouts. Since, not a very long time in the life of an individual is but an hour in the existence of the Great British Empire, and the Great British Empire was the economic superpower before the USA, let’s have a look as some examples in its credit history.

The first example is that of the South Sea Company, a historic government debt scam stretching from 1711 to 1850 causing considerable financial harm to creditors and “investors” alike. The essence of the scam was to transfer all the government debt to the South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) while giving it exclusive and monopoly trading rights on slavery and the slave trade with the South Sea Islands and South America. Then create an investor frenzy for the company shares which inevitably collapsed and ruined investors while government got rid of its debts. The only winner in this scheme was the government. France, with John Law, ran a similar scam with the Mississippi Company combining it with excessive note printing.

Britain defaulted on the redemption of its notes in issue to gold. The British government and the Bank of England promised anyone who used its bank notes that it will give them gold at a fixed exchange rate for its notes upon presentation to encourage trust in its bank notes. It often reneged on this promise which is effectively a government default as “notes” are essentially promissory notes of government which settled in gold. Refusing to settle a promissory note in the promised gold is a default by government. The final gold default by the UK was in 1931. The historic narrative is walking off an unworkable gold standard while in essence it was a soft debt default by government by settling in a lesser value than gold giving note holders a “golden haircut”. The rate of exchange was: “in exchange for legal tender at the fixed price of £3 17s. 10-1,-d. per standard ounce” which at a gold price of around £1520 presently gives an idea of the value lost to no longer having convertibility to gold.

Britain needed a bailout from the USA after WW2 in 1946 to avoid being overwhelmed by its war debt taking a 54 years loan from the USA repayable in 50 annual installments from 1950, the last installment which was paid on 31 December 2006 (could not even hold to the original repayment terms turning it into a 60 years loan). One of few examples of a government being forced to actually repay a debt.

Britain once again needed a bailout in 1976, this time from the International Monetary fund when it had to apply for a £2.3 billion rescue package.

The default trick of governments during the 1970 and 1980’s was to cause inflation which boosted the nominal value of the GDP to reduce the debt to GDP ratio and to “inflate away” debt. Holders of pre-inflation debt were given an inflation haircut.

The latest default trick is Quantitative Easing which allows the central bank to buy excessive amounts of government debt while giving all savers an “interest rate haircut”, taken to absurdity by the European Central Bank when it created negative interest rates on government debt requiring savers (mostly pension funds) to pay governments interest for the privilege of lending them money.

The restructuring or pension fund reform introduced by France recently is another example of government default framed as a “pension reform”. The 2023 French pension reform law was navigated to implementation using every conceivable legal and political loophole to get it approved. It raises the retirement age from 62 to 64 and it may not sound like a default at all, but France has a mandatory state pension scheme as an unfunded contributory pension. The contributions of those working are used to pay the pensions of those in retirement. The government collects a dedicated pension payroll tax and spends the money rather than deposit it into a funded pension fund. The contract that government has with society is that it will be allowed to spend the money but in exchange will use current taxes as and when pensions are due to pay those pensions. Spending the money was easy enough, the “debt” due to pensioners is now too much for the French government so it unilaterally reduces the number of years which it will be obliged to pay pensions, reneging on its obligation to pay those pensions for having had the privilege of spending the contributions. The average life expectancy in France was just over 82 years in 2022 with France experiencing the same demographic problem of an aging population as prevails in most developed countries. France would have provided 20 years of pensions to its population before the “reform” and will now only provide 18 years of pensions. Pensioners are simply forced to take a 10% pension haircut (ignoring time value of money), in a soft default by France in 2023.

All political eyes turn to pension funds when government finances are stressed. The US government is no stranger to turning to pensions funds when budgets are tight.

“The history of public pensions clearly shows that there is a political, and economic, risk associated with ongoing retirement plans. The government can and does change the rules.

Another historical precedent associated with the navy pension fund occurred in the 1860s. Prizes had been plentiful for the Union navy during the Civil War; consequently the navy pension fund became quite large. In the aftermath of the war the fund had sufficient assets to pay all of its liabilities for the foreseeable future. However, at that point, Congress chose to expropriate the assets of the fund in order to help pay down the national debt. The fund’s securities were replaced with special issue bonds that were not tradable and that yielded smaller interest payments.”

A History of Public Sector Pensions in the United States, Robert L. Clark, Lee A. Craig, and Jack W. Wilson, Pension Research Council, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, 2003.

The USA, as did Britain, also defaulted on the promise to convert paper money to gold in 1933. First by Executive Order 6102 which prohibited the “hoarding” of gold and confiscated the gold holdings of US citizens. The next step was to pass the Gold Reserve Act of January 30, 1934, which reneged on the convertibility of paper money to gold.

The USA once again reneged on its promise to settle dollars for gold when in 1971 Nixon resiled on the Bretton Woods Agreement to redeem US dollars in gold. France, not trusting the US dollar or the US government’s promise, sent a battleship to the New York harbor with an instruction to collect its accumulated gold in the USA.

“In August 1971, French president Pompidou sent a battleship to New York harbor to remove France’s gold from the vault of the New York Federal Reserve Bank and to transport it to the Banque de France in Paris.”

A “Barbarous Relic”: The French, Gold, and the Demise of Bretton Woods, Michael J. Graetz & Olivia Briffault, Columbia Law School, 2016

President Nixon, on August 15, 1971, addressed the nation to state that the gold window will be closed. The 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement stipulated that all international trade payments can be done in US dollars and that the US dollar will be converted to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 per ounce of gold to instill trust in using the US dollar. The USA issued more US dollars than what it could ever hope to settle in gold and after France called its bluff simply defaulted on the agreement, calling the default “closing the gold window”.

The “credit history” of governments is quite shocking and certainly does not suggest risk free lending. Governments will unilaterally renege or default or impose haircuts directly and indirectly upon creditors whenever the need arises. Trickery with inflation and money creation is all fair game.

The next lending test is affordability, the income test, and the interest payment test. Can the debtor successfully repay the debt?

Government’s Debt Repayment Ability.

The questions to be answered are: can governments repay their debts given their current incomes, then provide for economic growth to see if perhaps future incomes can assist with repayment, and find the interest boundaries which governments can afford to pay on its debt. I’ll test for the UK and the USA. Governments are loath to repay debt and will only make the effort when forced through circumstance. The preferred route is to simply roll all existing debt and add to it running perpetual budget deficits. Debt repayment will be forced upon governments when creditors realize that repayment is unlikely, then it will be a game to get out first without causing a run on government debt.

UK Debt Repayment Ability.

UK government budgeted receipts for 2023-24 are £1,058bn and Total Managed Expenditure is expected to be £1,189bn. As expected, it is an immediate problem for the debtor’s expenditure exceeds its income which means the debtor has no money to pay off debt and in fact will be rolling all existing debt and then borrow even more money. At least, £1,058-£1.189=£131bn additional borrowing will be required. The UK has been running government budget deficits for the past 23 years non-stop. The harsh reality is that the UK has been running government budget deficits since the 1970’s with a surplus in mid-1980’s and 2000, all the rest deficits. UK government debt as a % of GDP was 36.8% in 2000 and is now at just over 100% of GDP. The two generations of debt formation now draw to an end with top heavy debt to be repaid by the next few generations. The answer to the repayment of debt by the UK is that it will never be repaid given its budget deficits from 1970’s (after which everybody abandoned fiscal discipline in favor of unbridled government debt formation).

It follows that we can only do a “what if” calculation about debt repayment by the UK government. What if they were to run a small surplus to repay debt? What if they have to pay higher interest? What if the UK were to go into recession and government receipts were to decline? What if GDP growth were to improve government finances? Well, let’s get on with it then.

- The starting point is Net Public Sector Debt in the UK. “Public sector net debt (PSND ex) at the end of May 2023 was £2,567.2 billion and provisionally estimated at 100.1% of GDP.” The £131bn deficit must be added to give an amount of £2698.2bn. The “PV” of debt.

- We simply can’t rely on government long-term budgets for guidance as governments always budget for deficit reductions over the next number of years and never actually get anywhere near that. We can, however, use GDP as the reference point and estimate future income, expenditure and a required Deficit or Surplus to reduce debt as a % of GDP to 70%, “pmt”. This approach does not repay any debt, in fact, the absolute level of government debt will continue to increase but it will reduce the debt as a % of GDP to a more macro-economic tenable debt level. This approach is also aligned with the reality that governments will never repay their debt unless they are forced through economic circumstance to do so.

- The next variable is interest rates, and we can use a data on current interest rates, “i”.

I will post the spreadsheet at the end of this article but here are the results of scenarios.

Scenario 1:

Debt: £2698.2bn

Interest Rate: 4.5% (average interest cost, presently 4.3%)

GDP growth rate: 1% (average for the period)

Balanced Budget: The UK will balance its budget and will not increase its borrowings in nominal terms while the debt to GDP ratio will fall annually given that the GDP is increasing annually. I’m not convinced that this is achievable politically or that the UK presently has any statesman/statesperson who can sell such a policy.

Result: It will take 40 years of balanced budgets to reduce the debt to GDP ratio to 70% of GDP.

Scenario 2:

Debt: £2698.2bn

Interest Rate: 4.5% (average interest cost, presently 4.3%)

GDP growth rate: 1% (average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 1% of GDP: The UK is currently running budget deficits of around 5% of GDP. This will require significant fiscal discipline to achieve.

Result: It will take 79 years of 1% Budget Deficits to reduce the debt to GDP ratio to 70% of GDP.

Scenario 3:

Debt: £2698.2bn

Interest Rate: 4.5% (average interest cost, presently 4.3%)

GDP growth rate: 1% (average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 3.5% of GDP: The UK is currently running budget deficits of around 5% of GDP. This will still be a political challenge to achieve.

Result: The debt to GDP ratio will continue to increase and will be at 120% in 50 years and 129.6% in 100 years.

Scenario 4:

Debt: £2698.2bn

Interest Rate: 4.5% (average interest cost, presently 4.3%)

GDP growth rate: 1% (average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 5% of GDP: The UK is currently running budget deficits of around 5% of GDP. Just carry on as before.

Result: The debt to GDP ratio will continue to increase and will be at 144% in 50 years and 168.7% in 100 years.

The only way in which the UK government can continue with its fiscal ill-discipline is to force the central bank to create the money required to fund the debt formation as it can’t be supported by the economy. All creditors will take yet another inflation haircut. The scenarios will also fall apart if inflation were to return as interest rates will have to increase beyond that depicted in the scenarios.

This is where the boundaries are. The UK must impose fiscal discipline and get as close as possible to holding budgets deficits to, at the very least, no more than 1% of GDP and hold it there for the next 50-80 years. Or. The UK continue with fiscal ill-discipline and force haircuts on creditors indirectly through inflation or directly in a credit default event like Sri Lanka did. The UK is currently already in a debt death spiral with a tiny window left to escape by the skin of their teeth…

Reducing budget deficits may be economically painful in the short-term as GDP may go negative for a period. The numbers indicate that the point of no return has already been reached with regards to the UK and all UK creditors may as well prepare themselves for that haircut for I can’t see the politician who will stand on a platform of reducing the budget deficit to less than 1% of GDP in the short term.

The UK fails the debt affordability test even while literally making zero provision for debt repayment. The 2023-24 budgeted interest cost is £116bn and it will borrow an additional £131bn which translates into borrowing more that what is required to pay interest. This is the bottom line; the UK borrows all the money required to pay interest on its debt and then borrows some more. Try that with your bankers and see how fast they call your debt for full and immediate repayment.

USA Debt Repayment Ability.

The USA Federal Government debt stands at $32,317.8bn as of writing this article. The 2024 Budget projects government receipts of $5,036bn and government expenditure at $6,883. The Budget Deficit is projected at $1,846bn. The USA GDP is projected as $27,238 and the Budget Deficit as a % of GDP will be 6.8%. Net interest is budgeted for $796 (using net interest understates interest cost) but using the same principles and scenarios as for the UK the results are:

Scenario 1:

Debt: $32,317.8

Interest Rate: 3.5% (average interest cost, presently 2.33%)

GDP growth rate: 2% (generous average for the period)

Balanced Budget: The USA will balance its budget and will not increase its borrowings in nominal terms while the debt to GDP ratio will fall annually given that the GDP is increasing annually. As with the UK, this is not expected to be politically achievable.

Result: It will take just over 29 years of balanced budgets to reduce the debt to GDP ratio to 70% of GDP.

Scenario 2:

Debt: $32,317.8

Interest Rate: 3.5% (average interest cost, presently 2.33%)

GDP growth rate: 2% (generous average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 2% of GDP: The USA is currently running budget deficits of over 6% of GDP. This 2% will require significant fiscal discipline to achieve.

Result: It will take 37 years of 2% Budget Deficits to reduce the debt to GDP ratio to 70% of GDP.

Scenario 3:

Debt: $32,317.8

Interest Rate: 3.5% (average interest cost, presently 2.33%)

GDP growth rate: 2% (generous average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 4.5% of GDP: The USA is currently running budget deficits of around 6.8% of GDP. This will still be a political challenge to achieve but is attainable.

Result: The debt to GDP ratio will slowly reduce to 70% of GDP in 56 years.

Scenario 4:

Debt: $32,317.8

Interest Rate: 3.5% (average interest cost, presently 2.33%)

GDP growth rate: 2% (generous average for the period)

Average Budget Deficit of 6.5% of GDP: The USA is currently running budget deficits of around 6% to 6.8% of GDP. Just carry on as before.

Result: The generous 2% GDP growth helps the USA to make tiny improvements in its debt to GDP ratio even at a budget deficit of around 6.5% annually and it will achieve a 70% of GDP ratio in 100 years. The requirements are that interest cost must not increase beyond the 3.5% average and the 2% GDP growth average must be sustained for 100 years. Any inflation, recession or even economic stagnation and the USA scenarios fall apart.

The USA fiscal positioning is less precarious than the UK but still not comfortable at all.

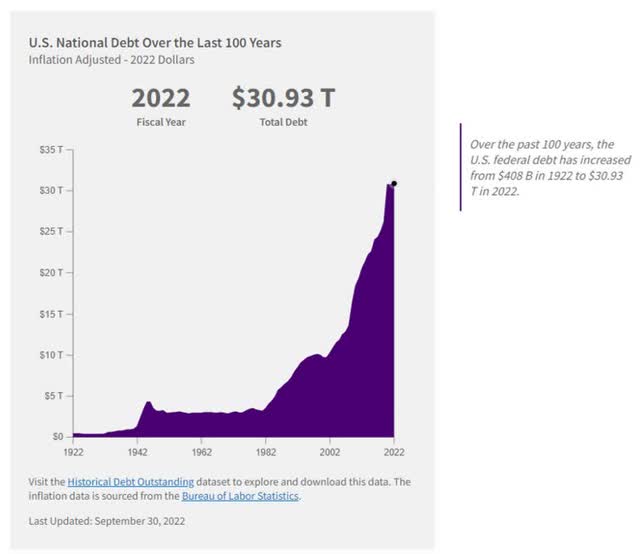

The US Treasury website shows how the USA debt has exploded over the past 100 years. This growth rate in debt will be impossible to maintain, if nothing else, the global economy cannot sustain such debt formation in the largest global economy. The creditors of the USA may face less risk of haircuts than UK creditors, but the risk is very much alive also for creditors of the USA.

US Treasury

The USA government also fails the debt affordability test and the USA government, as does the UK, also borrows all the money required to pay interest on its debt as well as borrowing a lot more. No creditor can sleep easy on USA debt.

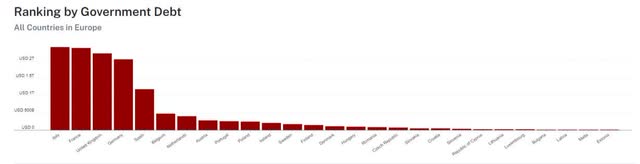

The debt positioning of all other countries pale to insignificance relative to the debt of the USA but here are the positions of all countries in Europe (includes the UK).

Data Commons

Data Commons: Place Rankings

Conclusion

History shows that governments borrow money on a generational basis, ever increasing debt formation until they break the economic system. Then governments are forced into debt repayment while economies go into recession or depression or at the very least into long-term stagnation. It is fairly obvious that government debt has already crossed the point of no return mark and are at peak debt. History also shows that governments will resort to any form of trickery or financial acrobatics to slip the leash of debt repayment and creditors will more often than not be taken for a ride. The best creditors can hope for is long-term fiscal restraint for it may just hold the line, but the likely outcome is that fiscal discipline will be enforced through economic calamity.

All government debt holders better get ready for the inevitable haircuts.

debt_repayment.xlsx

Read the full article here