The Fed study implies a major recession

The recently published Fed study (Distressed Firms and the Large Effects of Monetary Policy Tightenings by Ander Perez-Orive and Yannick Timmer) finds that 37% of US non-financial firms are currently close to default, or as they define in financial distress, and this is a “level that is higher than during most previous tightening episodes since the 1970s”.

The study concludes:

With the share of distressed firms currently standing at around 37 percent, our estimates suggest that the recent policy tightening is likely to have effects on investment, employment, and aggregate activity that are stronger than in most tightening episodes since the late 1970s. The effects in our analysis peak around 1 or 2 years after the shock, suggesting that these effects might be most noticeable in 2023 and 2024.

What this means is that the current monetary policy tightening will likely cause a recession much deeper and longer than any other recession since the 1970s, including the 2008 GFC, based on the percentage of firms that are in distress already. More importantly, the crisis is possible in 2023/2024.

Why? The study suggests that “the strength of the transmission of monetary policy depends on the aggregate distribution of firm financial distress”. The authors further explain their hypothesis:

Our hypothesis is that following a policy tightening, access to external financing deteriorates more for firms that are in distress than for healthy firms, while following a policy easing, external financing conditions do not change appreciably enough for the two groups of firms to trigger a differential response. As a result, investment and employment are more likely to fall for distressed firms than for healthy firms following tightening shocks, but to respond weakly and similarly to easing shocks for both types of firms. A corollary of this mechanism is that borrowing falls significantly more for distressed than for healthy firms after tightening shocks, and that borrowing for both types of firms does not respond significantly to expansionary shocks.

Basically, the financially distressed firms have limited access to capital during the monetary policy tightening cycles, which causes them to cut investment and reduce the headcount. Obviously, the more firms in financial distress, the larger the aggregate effect on economic activity.

But don’t expect the eventual monetary easing to end the crisis. The hypothesis above states that borrowing does respond significantly to expansionary shocks. That’s because the crisis solution is a function of bailouts and fiscal stimulus, in coordination with monetary stimulus.

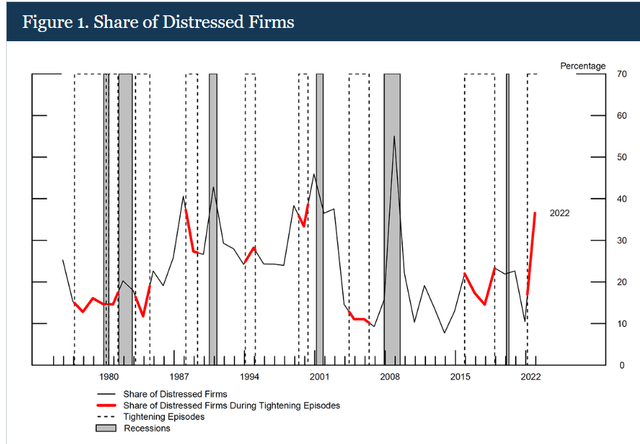

The chart

As you can see from the chart below, during the 1970s, and early 1980s episodes of monetary policy tightening, the percentage of distressed firms was fairly low, at sub 20%. Similarly, during the episodes 2005-2007 and 2016-2019, the percentage of distressed firms was also fairly low, with a somewhat higher percentage during the 1994 episode. The only comparable periods to the current situation were the monetary tightening episodes of 2000 and 1989, when the percentage of firms in distress also reached nearly 40%.

The Fed

Looking at the chart above, two things stand out.

First, during the monetary tightening episode 2005-2007 only about 10% of US non-financial firms were in distress, but that number grew to over 50% at the peak of the 2008 recession.

Second, the current monetary policy cycle started with only about 10% US non-financial firms in distress, but that number quickly grew to 37% with the data ending in 2022.

How bad will it be?

We know that the current monetary policy tightening episode continued in 2023, beyond the study’s data time frame, and we also know that the Fed is expected to continue hiking. So, there are two key questions:

- What is the current number of US firms in distress, for 2023, if the number was 37% in 2022? If the trend continued, and there is no reason to expect otherwise, the number could be well over 40% already.

- What percentage of US non-financial firms will be in distress by the time the Fed ends the monetary policy cycle, and what will the percentage be when the recession hits? Based on the trend, the percentage is likely to exceed 50%, possibly well beyond the 2008 number.

Basically, these numbers suggest that the forthcoming financial crisis could be more severe than the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, at least based on the percentage of firms near default. And that supports the key finding of the study that “the recent policy tightening is likely to have effects on investment, employment, and aggregate activity that are stronger than in most tightening episodes since the late 1970s”.

Implications

Given that 37% of US non-financial firms could be near default, and that this percentage could increase to above 50%, it’s reasonable to expect that many of these firms could default. Thus, we might be facing a major credit crunch.

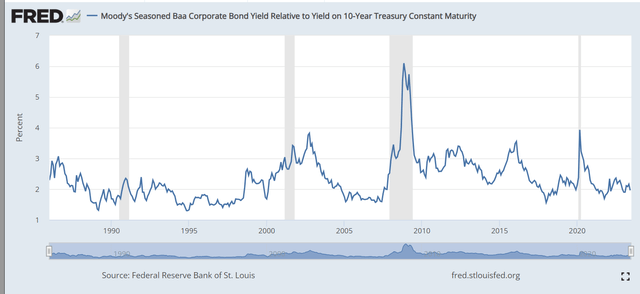

However, the credit spreads are currently very narrow, with the BBB-10Y spread below 2%, implying there are little credit worries in the bond market currently.

Well, we had the same situation prior to the 2008 GFC. Note, at that time there were less than 20% of US firms near default, but the number spiked over 50% as the recession hit in 2008, with the comparable sharp spike in BBB-10Y credit spread.

Thus, we are likely in a similar situation, except there were already 37% US firms in distress in 2022, thus the credit spread should be much higher already. This is likely an inefficiency that could be explored. Credit risk is currently artificially low, and it is likely to spike much higher.

FRED

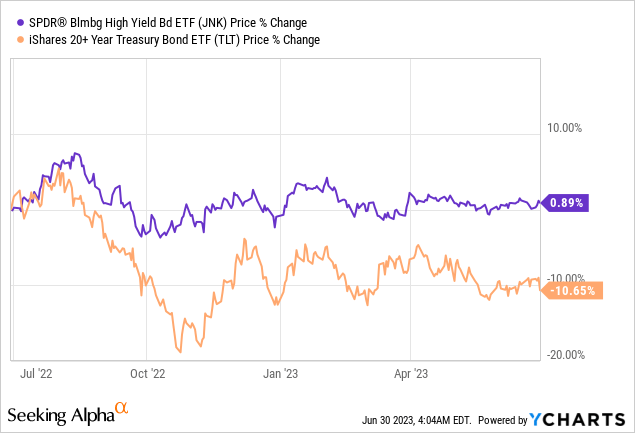

The obvious trade here is to short US high yield corporate credit, and one way to do it is by shorting (JNK) SPDR® Bloomberg High Yield Bond ETF.

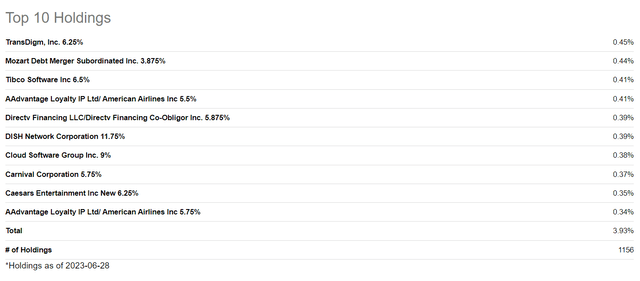

JNK includes 1156 bonds rated below investment grade or BBB. Thus, many of these bonds are likely issued by firms in financial distress, and many are likely to experience a downgrade or even a default as the recession hits. These are the top 10 holdings:

Seeking Alpha

What’s more interesting is that JNK is almost flat over the last 12 months, up by 0.89%, while iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT), which is an ETF that includes only longer-term US Treasury Bonds, is down by 10.65%. Thus, alternatively, the trade could be executed by shorting JNK and buying TLT, which is specifically a bet on widening credit spread, excluding the interest rate risk.

Conclusion

It seems like we are in “calm before the storm” when looking at the credit spreads, just like in 2008. But we are not, the storm is already here. Based on the Fed’s study, 37% of US non-financial firms were already near default in 2022.

Read the full article here