An inflammatory concept!

Who among us has ever caught herself praying for the stock market not to crash before her monthly bills get paid? If you depend on the stock market to cooperate with your hopes, ambitions or (god forbid) the timing of your bills, then you are probably at least somewhat familiar with a sensation best described as “millionaire poverty.”

Isn’t that an outrageous phrase! Conceptually speaking, “millionaire poverty” shouldn’t even EXIST, right? Oh sure, you know full well that you can’t justifiably complain about your financial situation, and yet you still feel like you’re scrambling, triaging and prioritizing expenses, trying to align the timing of your cash inflows and outflows and hoping for no surprises. There are three phases to having money; you’re either worried, waiting or wealthy. Only one of those phases appeals to you, and you’re not there yet.

But what even is “wealthy?” If you have ever experienced anything close to what is described in the previous paragraph, then you will probably agree with what I am going to say next. The definition of “wealthy” is this simple; you’ve still got $100 of income leftover at the end of THIS month, and you reasonably expect that you will have $101 of income leftover at the end of NEXT month.

How can you get there? In my experience (not that I know better than you or anyone else) nothing alleviates millionaire poverty quite like a consistently thrifty lifestyle combined with a healthy portion of dividend growth investing. If you find yourself attracted to this antidote then there remains only one question: implementation. For example, should you invest in a dividend growth ETF? If so, how do you pick which one is best? Or should you perhaps take a diversified approach and invest in multiple dividend growth ETFs? I’m going to let you answer that question for yourself… but only AFTER you contemplate the following thought experiment.

Picking Dividend Growth Investments.

Imagine two funds with two separate investment strategies. Fund A invests in large cap dividend growth stocks with at least 50 years of dividend history. Fund B invests in dividend paying companies that have been in existence for at least 100 years. If you own both Fund A and Fund B, are you more, less or equally as diversified as you’d be if you only owned one of such funds?

If you can answer that question based only on what I have told you so far, then you are misguided. To illustrate why, imagine that both Fund A and Fund B invest in the same companies but for different reasons. For example, let’s say both funds own Coca-Cola (KO) (a company that happens to satisfy both investment criteria for either fund). Does owning one company for two separate reasons make you more, less, or equally diversified than you’d be if you owned that same company for only one reason?

The answer should be obvious. Of course your portfolio risk and returns in this example depend exclusively on the financial performance of KO and the price you paid for the stock. The differing investment selection criteria of Fund A and Fund B is entirely irrelevant financially speaking – after all, if Albert Einstein and a drunken chimpanzee both buy and sell the same stock at the same time for the same prices, then they will both assume identical risks and garner identical returns. Such being the case, I’d argue that owning either KO outright, Fund A, Fund B or a combination of two or more of such investments makes literally no difference.

Oh, but what’s that you say? You say that the investment strategy of Fund A and Fund B also determines when and under what conditions they sell their KO shares, which in turn will certainly impact both returns and risk.

My response is that you are indeed correct – but that’s really a separate debate about whether it is more prudent to own stocks passively for the long-term, or to trade in and out of positions in the shorter-term. Why? Because it doesn’t matter whether the sale is based on an ill-advised hunch or because the stock no longer satisfies objective and predetermined investment criteria. To buy is to invest, and to sell is to trade.

So does it matter which dividend ETFs you buy? If you believe that what drives your long-term portfolio results is exclusively the purchase price and financial performance of the underlying stocks, then you should be ambivalent between buying shares of a fund like the Schwab Dividend Appreciation Fund (SCHD), or the fund’s underlying portfolio of stocks. If you prefer to own SCHD because the fund will add, eliminate and rebalance its underlying portfolio that’s fine – but that means you’re betting on short-term trading as opposed to passive long-term holding.

On the other hand, if you are determined above all else to own stocks passively for the long-term, then probably NO ETF suits your needs. I challenge any reader to name one fund- ONE SINGLE FUND – that is able to charge customers fees but never once sell a single share of stock for any reason. An ETF that does nothing. That would be a virtually impossible business model – which is precisely what makes it such a fabulous niche for individual investors like myself to inhabit.

An example of how an average, every day guy invests for dividend growth.

It may come as no surprise that I don’t own dividend growth ETFs. Instead, I own a cross section of companies that I believe, rightly or wrongly, are likely to pay and raise dividends in the future. Why do I believe that? Because the overwhelming majority of companies I own have (1) no debt or A-rated credit, (2) at least ten consecutive years of positive earnings, (3) consistent profit margins of at least 10%, (4) ten or more years of consecutive rising dividends, (5) rising book value over a ten year period, (6) stock buybacks, (7) upward trending earnings growth over the past ten years, and (8) products and services that improve the lives of their customers.

Do I believe that my selection criteria is superior to that of funds such as the Schwab U.S. Dividend Equity ETF SCHD? I have no idea. All I need to know is that by design, SCHD has higher turnover than my portfolio, and for better or for worse, that means more trading and less passive, long-term holding.

Do I think my portfolio will outperform funds like SCHD on a risk-adjusted basis? I have no idea. Not only that, I have every reason not to care. The reason why is because I live in a binary universe comprised of only two states of financial matter: (1) doing well enough, and (2) everything else. Only option (1) appeals to me.

And it’s just like I said to you before. “Well enough” means that I have at least $100 of dividends leftover after I pay my bills this month, and that I am somewhat certain that at the end of next month, I’ll have at least $101 dividends leftover after paying my bills. In my universe, the price vicissitudes and relative performance of my portfolio are the financial equivalents of neutrinos. They have virtually zero impact on either my spending or my dividend income and for that reason might as well not even exist.

Which specific stocks am I buying today with my dividend savings this month? The answer is Pfizer (PFE) and T. Rowe Price (TROW). Why those two stocks in particular? The answer is because they satisfy my eight investment criteria (as aforementioned) and carry dividend yields of roughly 4.4% apiece.

Do I think that the stock market has incorrectly priced TROW and PFE? Answer: I have absolutely no idea. What I do know is that I’ll be able to reinvest those dividends into more income-producing assets and thereby harness the power of compound income growth. The character Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street quipped “I only invest in sure things.” Why waste time trying to guess about relatively unsure things (like stock prices) when you don’t need to guess about the relatively surer things (like the power of compound income growth)?

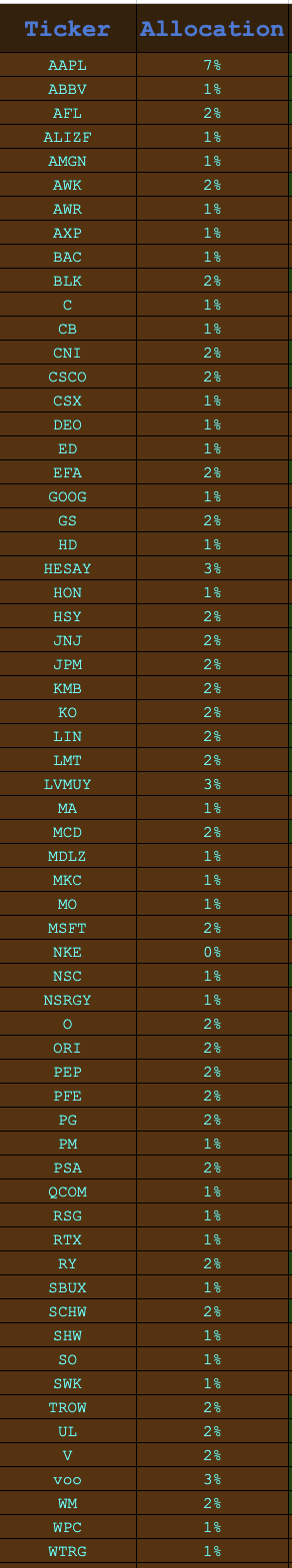

What do I own and in what proportions do I own it? And why am I telling you this? The answer to the second question is that I want to highlight any potential bias that I might have and also to provide an ongoing, real-time, real-life account of how an average schmo like me invests his own money year after year. Because after all, if I can do it, a well-trained golden retriever probably can, too… which segues aptly to the part where I assure you that I have no idea how you should invest your own money. The answer to the first question follows below:

Author’s portfolio (Author’s personal spreadsheet)

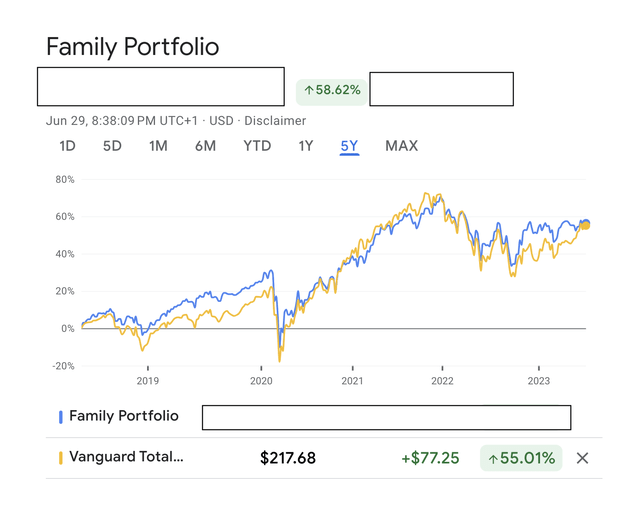

According to Google Finance, the five year performance of my portfolio against the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index ETF (VTI) is 58.62% compared to 55.01%, with a dividend yield of 2.61% compared to 1.54% for VTI. Most of the outperformance is due to just three lucky investments – Apple (AAPL), Hermes (OTCPK:HESAY) and LVMH (OTCPK:LVMUY) – and my decision to never rebalance. The higher yield is based on the fact that most of the stocks I own today pay dividends, and such cannot be said of the underlying portfolio for VTI.

Portfolio performance against VTI (Google Finance)

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here