The “Lollipop” Cut

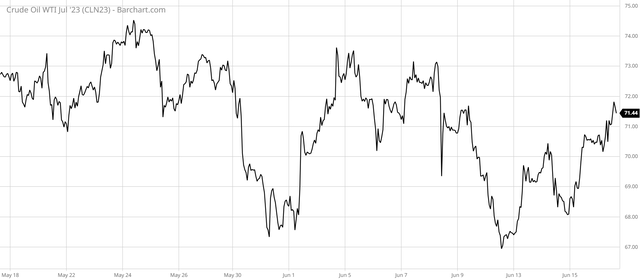

Two weeks after the OPEC+ meeting that extended earlier production cuts into 2024, adding a voluntary 1 mb/d cut from Saudi Arabia for July, crude oil (CL1:COM) fails to impress:

barchart

On the other hand, we have stabilized around $70; without the Saudi “lollipop” cut we might have gone lower.

Saudi Arabia may be trying to prop up the market until summer demand accelerates, but the Kingdom’s objectives aren’t fully clear. Some observers have suggested the Saudis painted themselves into a corner after Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman warned speculators they may be “ouching” so the Kingdom had to deliver some cut to retain credibility.

Yet, the fact the Saudis did follow through and the market’s muted reaction carry implications for the future:

- A return to very high prices in the $90-$100+ range probably won’t happen soon unless recession fears go away and we start seeing consistent and big inventory draws;

- An oil crash down to $50-$60 probably won’t materialize either; Saudi Arabia has demonstrated a commitment to intervene, not just this June but also back in April with the “surprise cuts” during the regional banking turmoil;

- All this suggests the $70-$80 range may last for longer; while much lower than 2022, these prices aren’t low in historical perspective. Saudi Arabia’s fiscal budget is also estimated to break even at around $80 oil.

It remains my view that $70-$80 oil benefits stocks with exposure to long-cycle investments. In practice, as national oil companies (or NOCs) account for much of this investment, the easiest way to ride the long-cycle trend is through oilfield services (OIH) stocks with international and offshore exposure. The $70-$80 range isn’t good though for many U.S. shale players that barely make money at these prices. Investors should therefore also ask themselves if shale companies with seemingly attractive valuation multiples aren’t priced so low because they are about to run out of economic inventory.

How Much Oil Supply Is Saudi Arabia Cutting?

OPEC+ didn’t introduce new production cuts. Rather the forum tried to signal a longer term commitment to cuts already announced before. These were extended through the end of the year and oil output from January-December 2024 will also be limited to 40.46 mb/d. For reference, pre-pandemic in Q3 2019 OPEC’s output was 29.39 mb/d plus 11.42 mb/d from Russia, for a total of 40.81mb/d. The drop may not seem big, but the IEA is now also forecasting that 2023 demand will average 102 mb/d, or 1.3 mb/d more than 2019.

The June meetings also yielded quota redistribution away from some African counties, which had consistently underproduced, to mostly the UAE. It doesn’t have immediate impact, but may help with better market management and assessment of OPEC’s spare capacity in the future. A big chunk of the cuts over the last year ended up as “paper cuts” precisely many OPEC members had unrealistically high baseline quotas.

Lastly, Saudi Arabia added its own temporary 1 mb/d cut for July; Prince Abdulaziz referred to it as a “Saudi lollipop” afterward. As this cut is just for July, it should only take 31 million barrels off global inventories. Again, not a lot but not too little either – it negates for example the impact of the 26 million barrel congressionally mandated sale from the strategic petroleum reserve.

Two further aspects are worth noting:

- If Saudi Arabia doesn’t like what it sees in the paper markets, it may decide to repeat the lollipop cut in August or at any other time; Prince Abdulaziz may be trying to create some uncertainty as a follow up on his earlier warnings;

- The Kingdom also raised its official selling price (or OSP) after the meeting; the OSP is set as a differential to an international benchmark and raising it incentivizes customers to buy non-Saudi oil. There is much speculation about the motivation but one theory floating around is that the Saudis want to force more visible draws from the closely watched U.S. commercial inventories. If the market is taking a wait-and-see approach, declines in U.S. inventories will probably be the first ones to get noticed.

The OPEC/OPEC+ meetings were also surrounded by speculation about cartel members being unhappy with Russian “cheating” as Russia markets heavily discounted crude to China and India. I am less sure what to make of it. The Western sanctions have forced a major realignment of global oil flows. Russia is selling more to India and China but has also largely lost its European market where OPEC can now get in. Saudi Arabia itself purchases Russian diesel, presumably at discount, which allows it to export its own diesel to the West.

What Is The Outlook For Oil Prices?

Predicting oil prices, especially in the short run, is proverbially a fool’s errand, but the OPEC events plus the muted market reaction, make me think the return to triple digit oil will get delayed. Investment banks including the bullish Goldman are also cutting down their forecasts; Goldman now sees WTI averaging only $81 in 2023. The EIA’s latest short-term outlook, dated right after the OPEC meeting, calls for $80 Brent in 2023 and $83 in 2024.

Wood Mackenzie thinks the 1 mb/d July cut will provide reasonable support for prices in the rest of 2023, leading to $85 average Brent for the year:

We forecast a significant implied global stock draw in Q3 2023, and we expect the OPEC+ 4 June decision to increase the implied stock draw for that quarter due to mostly the additional voluntary production cuts Saudi Arabia announced.

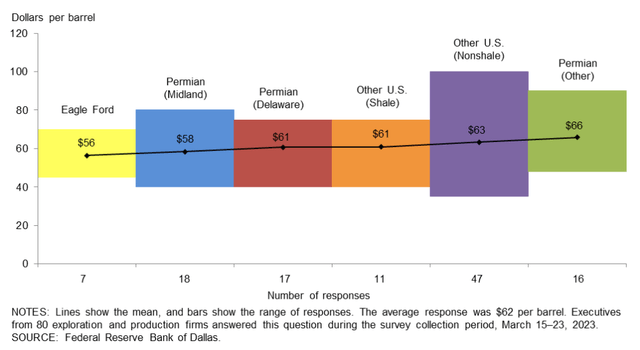

My base case is now that we may stay longer in the $70-$80 range unless summer demand really surprises on the upside or we start seeing a reversal in macro data from the U.S. and China. I personally don’t see how we go down to $50-$60 unless we have a repeat of pandemic-like restrictions. U.S. shale, the 2014-2021 swing producer, now faces higher costs and poorer inventory, so the supply response at $60 could be significant. The latest energy survey from the Dallas Fed shows shale full-cycle breakeven points north of $60:

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Could macro selloffs push prices lower temporarily? Yes, absolutely. But given the higher breakeven costs, I wouldn’t expect something like 2014-2016.

What Should Investors Watch For Regarding Energy Stocks?

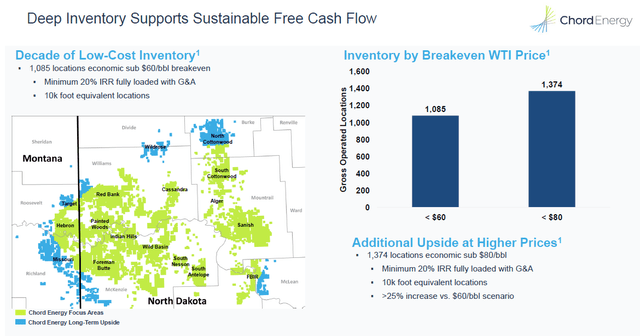

With $70-$80 oil, it is important to have a view on which assets will get developed/which won’t, what are operators’ full-cycle costs and how deep is the inventory. Much of U.S. shale may find itself unprofitable. We have, for example, companies that consider inventory with $60-$80 breakeven to be “low cost”:

Chord Energy Presentation

With $60-$80 breakeven, these guys won’t scare OPEC. Several years ago, OPEC wouldn’t have been able to cut big without ceding market share. However, the maturing of U.S. shale basins may have put OPEC back in the driver’s seat.

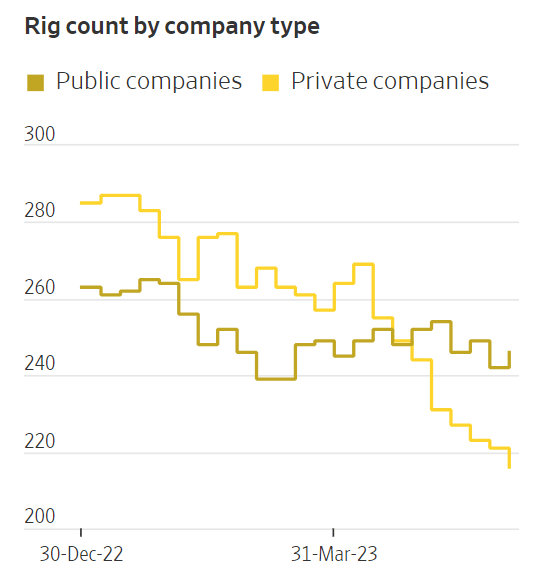

Of course, this is not to say there aren’t high-quality operators with cost efficiencies and long inventory such as Exxon Mobil (XOM), Devon (DVN), or Pioneer (PXD) among others. But at the margin things don’t look good, especially among private operators which account for most of the rig count reductions:

Evercore, WSJ

Being selective about U.S. shale should therefore be investors’ first guiding principle. Value-oriented investors like myself naturally get drawn to stocks with low multiples. But in today’s shale world low multiples are justified in some cases and may relate to the company having only a couple years of economic inventory.

Look For Stocks With Long-Cycle Exposure

On the bright side, $70-$80 oil (USO) is just fine for long-cycle international and offshore investments that frequently have breakeven costs of $35/bbl or below. In a way, oil not getting up to $100 may even boost the long-cycle thesis because operators can be more confident a surge in short-cycle supply won’t crash the market.

By most accounts, long-cycle investment continues uninterrupted. Here is the view of SLB (SLB), the OFS major that provides services to many such projects:

[We] maintain a constructive multiyear growth outlook. Through the first quarter, the resilience, breadth, and durability of the upcycle have only become more evident…To begin, the underlying demand, investments, and activity during this cycle are resilient, despite short-term economic and demand uncertainties. The combination of energy security, the initiation of long-cycle projects, and OPEC’s policy, sets the conditions for a de-coupling of the activity outlook from short-term uncertainties.

What Are Some Other Ideas In the Sector?

Apart from SLB, other ideas I like in this space include offshore drillers like Transocean (RIG) or Borr Drilling (BORR), offshore supply vessel provider Tidewater (TDW), and suppliers further back in the value chain like Oil States (OIS).

Services stocks offer a way to ride the long-cycle trend without having to invest in a NOC like Saudi Aramco for example. Certainly, there are independent companies focusing on long-cycle projects like Talos (TALO), for example, but a lot of this investment is also run by NOCs.

Services companies have also undergone their own capacity attrition during 2014-2020 when many rigs and vessels were scrapped. Supply chain issues and the rise in materials costs make it prohibitively expensive to invest in new capacity today. So what happens as result is that the owners of the fewer still functioning assets can bid up their prices as there is no supply alternative. According to industry reports the rig market is close to being sold out:

We expect contracting activity to remain light in the near term as the industry is largely sold out of hot and warm assets,” Evercore said in the report. “However, we believe floaters could end the year higher on a rig-year basis. The marketed utilization for seventh-generation drillships at 95% is the highest it’s been since 2016, with only five cold-stacked and eight newbuilds available.”

The firm also noted that sixth-generation drillships have also increased to the low 90s percentage range, up significantly from a pandemic low of less than 60%, with only nine cold-stacked and three newbuilds available.

The report also said that contract terms “are likely to trend higher from the eight-month average currently, with a $500,000/day-plus dayrate expected in the coming months.”

The reality is that for a NOC like Petrobras (PBR) with possible breakeven as low as $20 on some projects, a rise in rig dayrates from $400,000 to $500,000 or even $600,000 won’t move the needle as much on the investment decision when oil is $70. However, for the few services providers that can offer these assets, the dayrate increase will have tremendous effect on the bottom line due to operating leverage.

Bottom Line

Whether the Saudis wanted to prop up the market until summer demand kicks in or they have a deeper plan remains to be seen. However, the 1 mb/d July cut plus the market’s muted reaction probably point on balance to an intermediate $70-$80 price range for the time being and take off the table the extreme scenarios.

If my assessment of the price regime is correct, investors should scrutinize their shale investments, particularly, companies with low multiples that may have inventory problems. The best long ideas in my view will now be among stocks with long-cycle, offshore/international exposure and specifically among services providers that own scarce capital assets.

The oil trade isn’t dead but investors may want to rethink where in the sector they focus. When oil is $100, all energy stocks do well and the higher cost ones may even do better due to greater “torque.” A $70-$80 regime though calls for a more active approach to investing.

Read the full article here