As has been well documented, 2022 was a pretty bad year for Global Equity markets, which was compounded by the Global Bond Market being decimated, and having its worst year ever! As is usual whenever there is fear in the market, this leads to many investors questioning why they were holding equities in the first place. With inflation running rampant, and the Fed having ramped up rates at the fastest pace for 50 years, the question appeared to be valid. Why would I hold an equity with all the uncertainty of a looming recession when I could be finally be getting a 4%-5% return on a Government Bond (virtually) risk free?

As is usual whenever discussing “performance” of a particular investment, one has to make sure one has defined their time horizon. Each of the following statements are equally true, the difference is one’s time horizon and entry point.

-

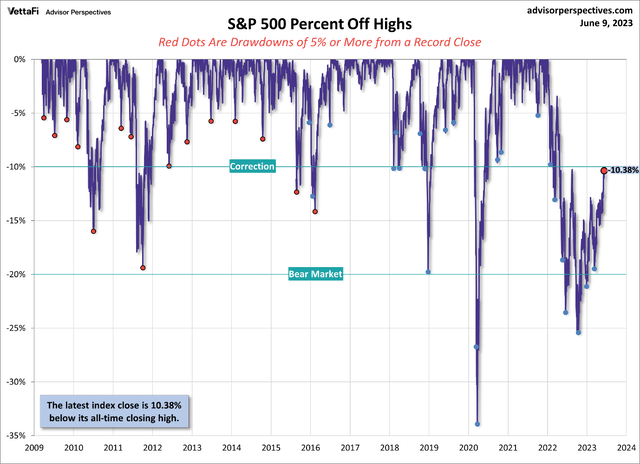

The S&P 500 is down 10.4% from its all time high

Advisor Perspectives

2. The S&P is up 12.4% in 2023

Seeking Alpha

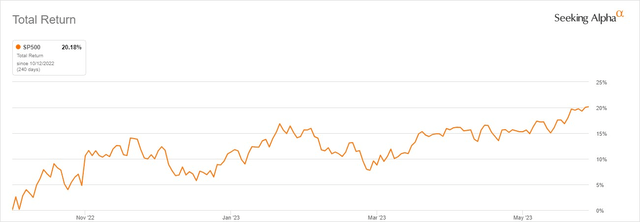

3. The S&P 500 is up 20.2% from its 2022 lows

Seeking Alpha

I’m assuming that in posing the question asked above (why hold equities in the first place), first and foremost one is taking into account the potential risk in terms volatility and draw-down potential, within the time horizon in mind. I.e., if this is cash that will be needed in the short to intermediate term, then equity market risk is just not appropriate for this cash, and should be invested in something far less risky and volatile.

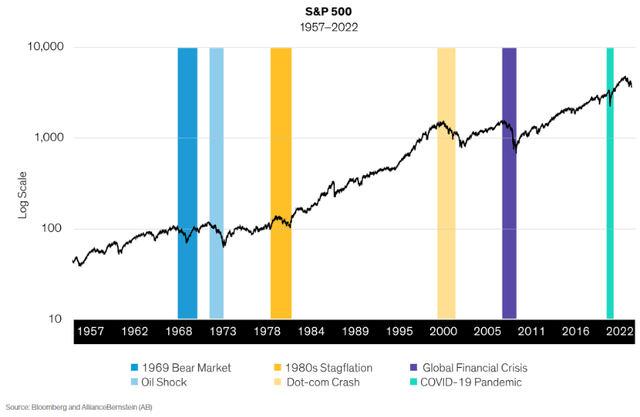

So why should I invest in equities in the first place? Well, plain and simple, by investing in an Equity, one is investing in the riskiest part of the capital structure. And as compensation for that additional risk, one should be compensated appropriately. Which means that one has to be cognizant that returns will be more volatile, both to the upside, as well as to the downside; as the flip side, or a price one has to pay for being an Equity holder, is volatility. Which, particularly during periods of market fear, is exasperated (both to the upside and downside) by being determined as a function of investor’s emotional psyche. But for long term, patient investors, investing in equity markets has paid off handsomely.

Bloomberg

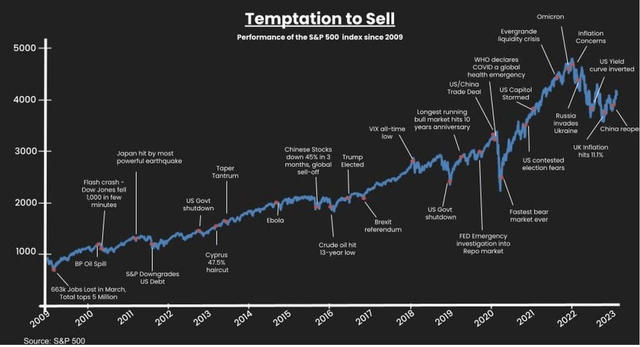

If one had a crystal ball and could see with 100% certainty how the future would evolve, it would probably be far easier to invest. Almost by definition though, the world is uncertain with a myriad of different variables, which opens up the possibility of a range of outcomes, each with a varying degree of possibility. Probabilities of different outcome are constantly evolving too, as are extreme possibilities of an event, both good and bad. The result, is that there are always reasons to sell, and fears that may or may not come to fruition, but for long term investors, the long term upward trend is clear.

S&P 500

As is quite clear in just about every financial disclaimer that is never read, past performance is no guarantee of future results. When it comes to financial markets, circumstances can change-sometimes quickly and unexpectedly. Nonetheless, it is not unreasonable to assume that “average” long term return expectations should not be too dissimilar from prior long term cycles.

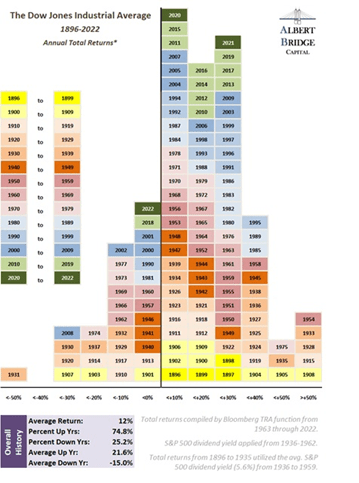

So how does the stock market perform on average? What can an investor expect on average? That’s a question that is pretty much impossible to answer, as historically, markets, and indeed economies for that matter, have undergone such a wide range of metrics, that an “average” return can only really be looked at in the context of the timeframe in question. Stock market performance (as evidenced below by the Dow Jones histogram) shows that on a calendar year basis, the market has fallen more than 50% at one extreme, and at the other extreme has risen by more than 50% on several occasions.

Albert Bridge Capital

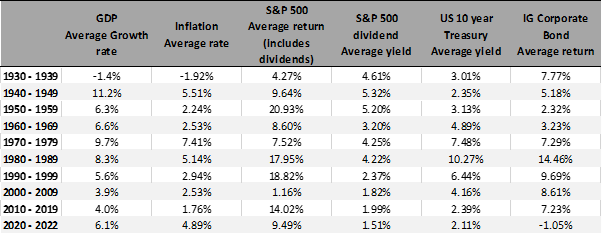

I have summarized below the key average annual returns by decade, and as is clear, the “average stock and bond market return” bears little to no resemblance to the absolute state of the economy when considering the annual GDP growth rate or the average inflation rate:

FRED

Note: the table is summary I have put together, using GDP and inflation data from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (Federal Reserve Economic Data | FRED | St. Louis Fed), and the Investment Grade Corporate Bond Return computed from yields on Moody’s Aaa and Baa bond yields on the aforementioned FRED website).

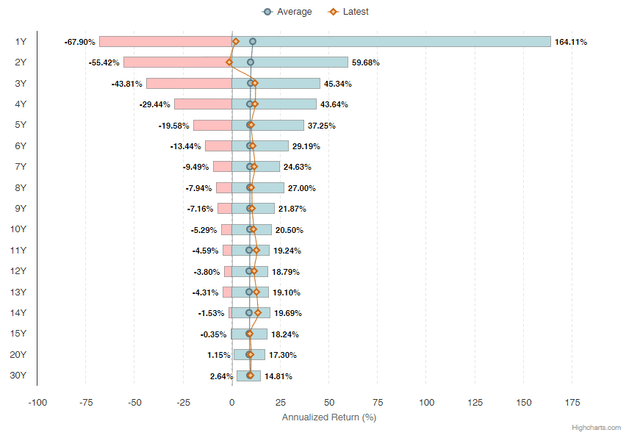

So although the concept of an “average” return does not exist, and over the shorter term the range of possible outcomes is incredibly wide and somewhat extreme, the longer the time horizon, the outcomes tend towards what one could conceivably consider to be an “average” return, circa 9%, and the range of possible outcomes is much narrower too.

highcharts.com

Over any 1 year time horizon, although the US stock market has been positive about ¾ of the time, performance has ranged anywhere between -68% (in July 1931) to +164% (in July 1932). If one increases the time horizon to 3 years, then the market historically has been positive for about 86% of all rolling 3 year periods, and the ranges have been between -44% annualized (in July 1929) to +45% annualized (in March 1933). If one can increase the time horizon to 10 years, then historically, over all 10 year rolling periods, 98% of the time performance has been positive, with the range being between -5% and +21% annualized performance.

There are a number of key takeaways that I would like to emphasize that comes out of this analysis:

- Over the short term, whether one is making or losing money on their investment, is almost a flip of the coin. However, the longer the time frame, the more likely it is to be making money.

- Even though we have demonstrated that long term average returns are quite stable, returns in the market are ultimately out of one’s control. The difference between the best outcome and the worst outcome was a function of the time and environment that one was born into, and the results on offer at that time. Which is obviously only known many years later. One has no control nor influence over the stock market, nor inflation or interest rates for that matter. One can only attempt to control one’s own personal variables, such as asset allocation, discipline and diversification.

- Being disciplined to one’s investment plan, despite all the “background noise” is key to success. In order to being able to achieve the somewhat stable long term “average” return on offer, one has to be comfortable investing through uncertainty. If you wait until the perfect entry point and things are looking wonderful, then it’s likely that if you have reached this conclusion, then so has everyone else, and market prices have already discounted the coming good times. By the same token, when things look so bleak that the world looks about to be ending, the market has already reflected the dire reality in its pricing, and that is the best time to take advantage of the wonderful returns likely to be on offer.

- Even by being disciplined, one can go through long term periods of relatively poor performance. There are no guarantees for anything; however, the longer the time frame, the more likely it is one can eliminate the extreme downside scenarios.

I hope that I have been able to demonstrate that patience is a virtue that is more likely to be rewarded the longer one can keep disciplined, and there is a higher chance of achieving the “average” long term return. One suggestion to being able to block out the background noise and maintaining discipline over the long term is to consistently buy into the market, irrespective of whether you feel stocks are trading “cheaply” or expensive. Or if you are expecting good times or bad.

But is that necessarily so? Perhaps one could do better in attempting to “time the market”? I hope to explore this question in a future post. Stay tuned!

Read the full article here