Thesis

For decades, the Canadian banking sector has been locked in a perpetual stalemate uniquely held together by a combination of interdependence and regulatory safeguarding. When deployed in an oligopolistic and relatively stable market structure, the concept of mean reversion can be a powerful strategy to consider here. Coupled with attractive fundamentals, holding a mean reverting index of Canadian banks offers the opportunity to consistently reinvest when one bank market cap dips relative to others, creating value over time insofar as this stability continues.

Notes: Big 5 banks are: RBC (RY), TD (TD), Scotiabank (BNS), BMO (BMO), and CIBC (CM). Unless otherwise stated, all figures in CAD Dollars.

Why the Stalemate?

It would be forgivable if you were avoiding banks like the plague right now – and much like the plague – banks can and often do infect one another. Financial contagion spreads fast and can collapse an institution both abruptly and without remorse. History, both past and present, is rich with such examples.

Between the 5 major Canadian banks exists an oligopolistic market structure and interdependent equilibrium, where no firm holds a majority market capitalization or industry dominance. And unlike their US counterparts, these banks are protected by a firewall of regulatory barriers, effectively outlawing all external competition (with few exceptions). This in turn creates an environment of extreme stability which prevents any one firm from attaining industry dominance.

If, for example, one Canadian ‘Big 5’ were to fail, the contagion would be extreme and immediate. So, while the Canadian banks certainly do fiercely compete with one another, they also depend on one another much more so than in the US. Therefore, no bank wants to completely kill another, and they compete in a much more stringent environment of regulations to promote tame risk management practices.

With little competition, in Canada the big 5 banks control more than 80% of the market share by deposits. Conversely, in the US, the top 5 bank market share is closer to 50% and there are roughly 4500 chartered banks. For context, in Canada there are ~80 banks in total, or 1 for every 438,000 people. In the US, on the other hand, this figure is approximately one bank for every 78,000 people – representing a per capita difference of nearly 6x!

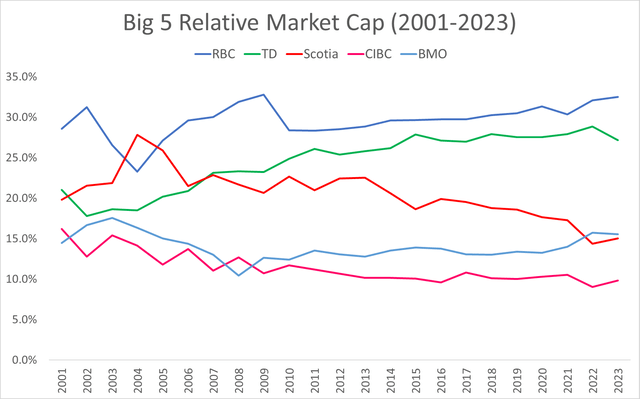

This seeming stability in the Canadian banking sphere can be seen in the figures below:

Author’s Calculations

| 2001-2023 | RBC | TD | Scotia | CIBC | BMO |

| Mean Market Cap Share | 29.6% | 24.5% | 20.5% | 11.4% | 14.0% |

| Yearly Standard Deviation | 2.1% | 3.5% | 3.0% | 1.9% | 1.6% |

Hamilton ETFs ‘HEB’ Canadian Bank Mean Reversion ETF

Hamilton ETF’s Mean Reversion Canadian Bank ETF (HCA.CA) is a great way to execute on this strategy. As stated in their investor page:

“HCA attempts to take advantage of these tendencies (mean reversion and market stability) by rebalancing the portfolio quarterly and investing 80% of the portfolio in the 3 banks which have recently underperformed, and 20% in the 3 banks which have outperformed.”

Please note that HCA.CA holds a 6th bank, which is National Bank (NA), as it is sometimes included in the list of major Canadian Banks.

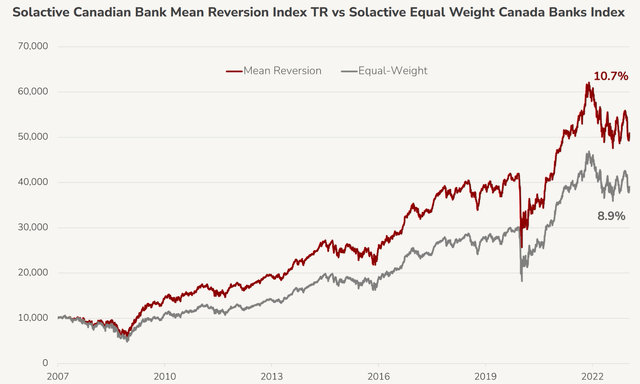

The results speak for themselves. When backtesting from 2007 to 2023, the mean reversion index compounds at a rate of 10.7% per annum versus just 8.9% of the equal weight index. The result is a cumulative outperformance of a highly material ~20% in this time period.

Hamilton ETFs

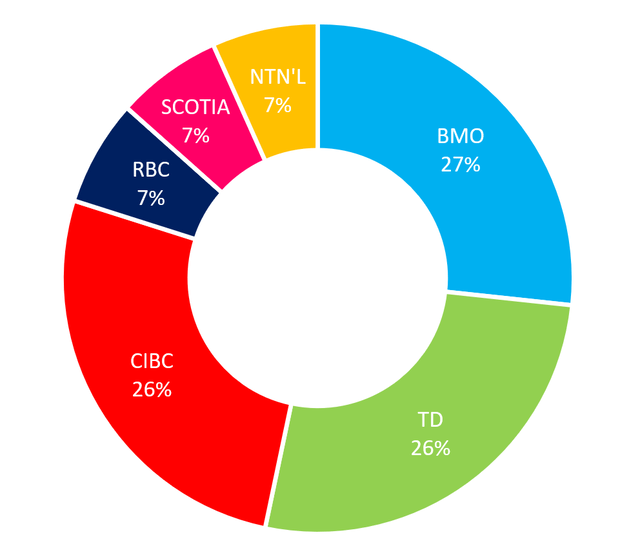

Currently, HEB’s holdings look like this:

Hamilton ETFs

In the most recent reporting rebalancing quarter, HEB overweights CIBC, TD, and BMO due to their underperformance, and underweights RBC, Scotia, and National due to their overperformance.

This takes advantage of swings in relative market cap which may not be justified in the model of perpetual stalemate as has been the case in Canada.

Canadian Bank Fundamentals Strong

Finally, one must consider not only the stability but strength of the Canadian banking sector. Currently, the Big 5 Canadian banks boast an attractive dividend yield of between 4-6%. In 2021, Canadian banks returned $21.6 billion back to shareholders in the form of dividends and it has been a driving source of compounding for the banks over the decades. Additionally, Canadian bank PE ratios have an average of around just ~10x significantly less than the TSX and S&P overall ratios respectively of 16.4x and 22.2x respectively.

Despite their cheapness, Canadian banks have a fast growing customer base. Canada is adding more to its population than other developed countries. By 2025, the country will welcome an additional 1.5 million immigrants, all of whom will need banking services.

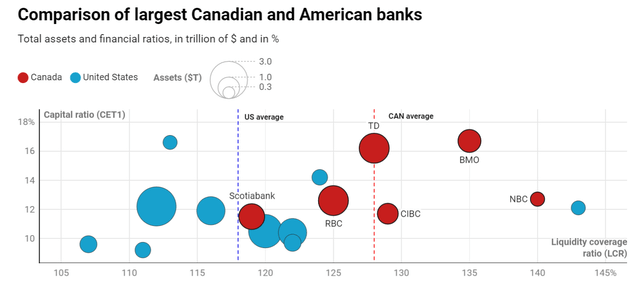

Canadian banks are also extraordinarily well capitalized. Canadian banks have greater liquidity coverage ratios and on average a higher portion of tier 1 capital (CET1) when compared to their US peers as illustrated below.

CPA Canada

Canadian banks are also better prepared to deal with higher rates for a variety of reasons. For instance, Canadian mortgages are generally variable structure while US are generally fixed, giving Canadian banks the ability to charge higher interest payments sooner. Furthermore, Canadian banks are far more diversified in their assets than the US, and do not take on excess duration liabilities as in the case of SVB.

Risks

There are numerous risks which could jeopardize the success of this strategy. Firstly, a ‘mean reversion’ strategy is reliant on the mean actually returning to some predictable, stable, and long term trend. So, while the Canadian banking industry has certainly been experiencing this phenomena, there is no magical guarantee that it would continue. Should we see continued volatility in rates coinciding with different approaches to duration management as an example (as seen in the US), the performance of the Canadian banks could begin to materially differ in the long run. Additionally, black swan events such as derivatives mishaps, scandals, political eruptions, and situations of that type which are idiosyncratic in nature could significantly differentiate the market dominance, or lack thereof, of any 1 bank. As stated previously, much of the Canadian banking sector stability is dependent on government control and regulation – particularly to ensure low risk balance sheets and exclude competition. Should we see a reversal of government policy to deregulate the banking sector and allow competition, it would give banks greater agency to ‘control their own destiny’ rather than be locked into a state of perpetual equilibrium. All of these risks on their own could shake up the Canadian banking sphere and disrupt a long history of stability.

Conclusion

Canadian banks differ in many ways from their US counterparts. Most notably on the riskiness of their balance sheet and nature of competition. In turn, we have seen each of these respective banking systems develop a reputation over time. In the US, banking can be characterized as an extreme sport for investors, picking between an investment universe of over 4,500 names is never easy and certainly possesses a far more extreme risk return profile. Canadian banks on the other hand are differentiated more than anything else, by name and logo rather than size and function. The natural stability offered in this sector can be exploited using a mean reversion strategy which has so far been highly lucrative as exemplified by Hamilton ETFs. When considering the fundamental attractiveness on a cost and value perspective as well, Canadian banks can serve as excellent sources of returns through dividends and capital appreciation within portfolios. If the state of equilibrium continues, investors could be rewarded generously for their patience and trust in Canadian finance.

Read the full article here