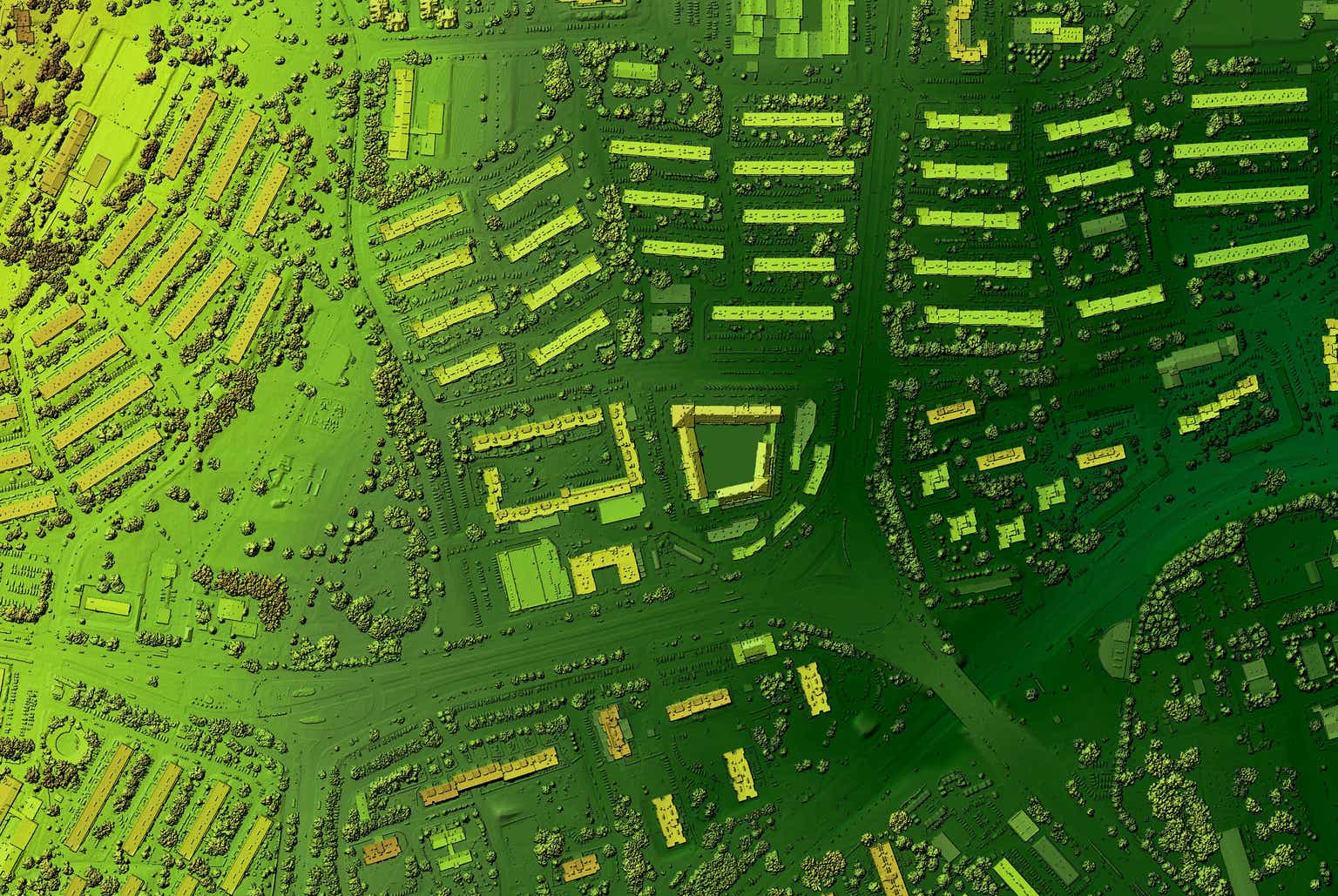

Geospatial data has the potential to revolutionize investment decision-making by providing investors with insights into the spatial dynamics of different markets and assets.

Transcript

Oscar Pulido: Welcome to The Bid, where we break down what’s happening in the markets and explore the forces changing the economy and finance. I’m your host, Oscar Pulido.

Have you ever wondered if the weather can impact your investment decisions? What if we could map the impact natural disasters have on economies, or immediately understand the impact of a geopolitical conflict on your portfolio?

Geospatial data provides information on the physical location and characteristics of assets, infrastructure, and resources. This data has the potential to revolutionize investment decision making by providing investors with insights into the spatial dynamics of different markets and assets.

To help us gain a better understanding of this new and cutting-edge investment trend and how this information is gathered and used, I’m pleased to welcome Joshua Kazdin and Mike Pensky, who are both part of BlackRock’s active investment business. And we have spent the last several years developing a geospatial investment capability and bringing these insights into active investment portfolios.

Josh, Mike, welcome to The Bid.

Mike Pensky: Thanks for having us.

Josh Kazdin: Glad to be here!

Oscar Pulido: Mike and Josh, you both work in the active investment business, which I think of as you’re trying to outperform the market, and in order to do that, you have to have really unique information and insights that allow you to do that.

I think historically, you’re meeting with company managements, you’re analyzing the financial statements of companies in order to develop those insights, and I think some of this still happens, but another way that you can do it – and that you guys have pioneered – is this thing called “geospatial data”. So, what is geospatial data and how did you start on this project?

Mike Pensky: So, Oscar, the way to think about geospatial data, it’s just data that’s all around us. They can be objects or events or really anything that has a location associated with it near the surface of the earth. Right now, you’re sitting in the world somewhere, right now you’re sitting here with us. Outside it might be really hot. People might be walking around the commercial district, the airport at the local city might have a lot of activity, there are a lot of hotels that might be booked in the area. All of these are concepts that are geospatial in nature, they’re associated with the location.

And so, what are the data that are associated with it that we can measure? We can measure the extremity of temperatures; we can understand the foot traffic around various stores and retail locations. We can understand what hotel bookings look like. We can measure the GPS traces on trucks as they’re moving around the city.

All of these happen in certain locations, and they have investment implications associated with them that we can actually leverage in our portfolios. Ultimately, to us, geospatial data is about getting information that’s more timely, that’s different than what you can get from other data, and it really is associated with actual real human economic activity happening in real time.

Oscar Pulido: Maybe Josh, touch on why did the two of you partner up on this initiative?

Josh Kazdin: Part of the reason why, honestly, was I had a couple of friends in San Francisco who wanted to start a family, and usually when you start a family, you move out of the city and you go out into the suburb somewhere, maybe someplace that has a little bit more room to move. You have a yard for your kid to run in, there are schools. And every year after they moved out of San Francisco, they had to pack up their home and get into a car and drive away because there were wildfires. In California, you fear wildfire season every year. That cost on a family, on a community is really hard to quantify. We wanted to better understand how extreme weather events were ultimately impacting households, businesses, and the markets.

A couple of years ago, Mike and I decided to explore what were the effects of FEMA disaster declarations on economic activity at the county level in the United States. By the time we got comfortable trying to understand that relationship, the pandemic hit. And that became an entire geospatial problem in and of itself. Social distancing data started to get released both in the United States, in Europe, and across the world. And our group started to pull in that data and use it to forecast which areas were going to have a government shutdown, which businesses were going to be impacted, and how that was going to ultimately impact our portfolios.

The minute that we got comfortable with that, Russia invaded Ukraine. And in the horror of that atrocity, we immediately sprung into action to try to understand how the war was ultimately going to impact our clients’ portfolios. Where were the investments themselves and ultimately, which companies were likely going to be impacted?

Certainly, stranded assets during that time were much more about a McDonald’s in Moscow than it was anything buried under the ground. Across each one of these areas, geospatial became a really critical piece to understanding either a risk or an opportunity that would impact our client’s capital.

Oscar Pulido: You’ve both painted this really interesting picture, this sort of lens on the world that you are uniquely seeing with all these data points. You talked about airport activity and talked about social distancing activity and the insights that provided. But I can’t help but think about the sheer quantity of all the data points that you’re looking at. How should people think about what you’re doing in the geospatial realm with this term big data that gets talked about a lot?

Josh Kazdin: So, our team’s motto is that we turn data into alpha. Usually that data can come in three different ways. People think either it’s traditional, it’s big, or it’s alternative. Let’s just give a quick overview of each one of those.

Traditional data is the usual suspects of financial information that people have been using over the last century to try to understand markets.

This can be everything from financial statements to the SEC, macroeconomic releases, industry reports, analyst ratings, even returns themselves. Those are just the traditional data sets that we use to think about markets. Usually, you can put it into a nice spreadsheet, load it up on your computer and make a decision about what you want to invest in.

The bigness of data, however, covers both the size as well as the computing resources that you need to explore that information effectively. We’re not talking about the megabytes of a PDF that you might download, or the gigabytes of an update to your iPhone, we’re talking about terabytes or petabytes of data that require a huge amount of computing power to be able to understand.

Alternative data can be big or small, but usually it’s strange, unstructured, not mapped to an investment that you’re trying to analyze. So, if you are thinking about what people are searching for online in terms of a product that they might want to buy, or as Mike mentioned before, the GPS trace in trucks as they’re moving through a supply chain or news that is coming out halfway across the world in a different language. What topics are they talking about? What is the sentiment? What companies are implicated by that? All that might be classified as alternative data because it’s going to be hard to map to an investment. It’s going to be difficult to wrangle, but it could ultimately lead to an informational advantage, that you can use to better make investments. But in order to use it effectively, you need to extract, translate, map, and transform it systematically and at scale to generate alpha.

So, in short, traditional data can be big, alternative data can be small, but by bringing all types of data together with some strong economic sensibility, we’ll find value that’s often overlooked by others in the market.

Oscar Pulido: Maybe going to the geospatial, you mentioned terabytes and petabytes. I’m not even sure I knew that second word to be honest. But how are you gathering all this information? I understand that it’s insightful when you have it, but just gathering it and organizing it must be a lot of what you’ve spent your time on in these last couple of years?

Mike Pensky: The way I think about our geospatial effort is that it’s been trying to marry three disciplines that are actually a little bit different from each other. The first one is technology and computing. The second one is data science, and the third one is economics or finance research. Let me take you through each one of those in turn, just to give you a bit of a flavor of what that means.

From a technology perspective, Josh just talked about big data, geospatial data can be really big. Just to give you some numbers, our geospatial platform up to this point has processed about 20 terabytes of data and we’re really just getting started from my perspective. To put that into context, the entire printed collection of the US Library of Congress is about 10 terabytes of data. We’ve already exceeded that and we have a lot more to go. So, you really need a lot of expertise in computation and technology to be able to run operations on that type of data.

The second one is data science. Some of the data we use is publicly available, some we purchase, but in any case, we need to find ways to actually glean insights out of it.

One very simple example that’s been a very important part of our project is trying to tie companies to physical locations. What we’ve done is we’ve purchased a database of about 200 million points of interest, so where companies are located around the world. What this database has is fairly fuzzy detail on what each location is. Maybe something relating to a website address or a description, but it really doesn’t map very cleanly to tradable companies. What we’ve had to do is create data science models that give us a lot of accuracy in being able to map those 200 million locations to 60,000 tradable stocks. That is actually a really hard data science problem; it requires some really complex models, but that again is something that we really need to leverage in this effort.

And then finally, more traditional finance economics research. This is the most nuanced, but maybe also the most interesting. So, we have the data, for instance, NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, gives us data about the temperatures on the surface of the earth. We get it effectively as multicolored images. we have the data, it’s free. So, what do you do with that? How do you actually glean insights?

This is what we do every day. You take some hypothesis, so this might impact economic activity somewhere. We run that through our research process, testing what activity it might impact, test how we might be able to implement that in portfolios. And really the goal is to get a lot of comfort that over an intermediate horizon, we can reposition our portfolios in response to that data as we’re getting it and benefit our clients.

Oscar Pulido: Do you have a maybe more specific example of how that happens. Because you’ve talked about the sheer quantity, the two times the library of Congress is what I heard in terms of the processing and you’re still going, so you have a lot of data points but being able to make an investment decision from them, and what would be an example of how you use maybe some of the weather related information that you gather?

Josh Kazdin: Let’s stick with the example of extreme temperatures just for a moment. In one of our first experiments looking at this topic, we observed that GDP growth in outdoor related industries tended to drop during periods of abnormal amounts of extreme temperatures, either extreme cold or extreme heat. Last summer, we observed hotter than average temperatures in Europe.

This had an immediate impact on economic activity. You can’t put a new roof on a house when it’s above a hundred degrees outside. You might not want to go to an outdoor event, but both can be moved into the future once temperatures start to moderate.

So, the data that we’ve looked into suggested that a drop in economic activity can oftentimes be temporary. This rebound effect is something that is often underappreciated in the market, and it creates an investment opportunity. For a macro investor, you might invest differently in European equities versus other opportunities during periods of extreme weather or extreme temperature, and then explore getting back into those positions after temperatures normalize.

Mike Pensky: Another example I would give you is measuring the availability of renewable energy. To give you an example about 20% of the EU power generation comes from solar and wind right now and so as a result, the winter of 2021 to 2022 was a little bit of a tough one for Europe because it coincided with both very cold temperatures, so more demand for heating, but also at the same time as following a period of calmer winds. One of the things we were able to find is that if you intersect the location of wind farms with the amount of wind that blows across them, you can measure how much wind power will be generated as a result.

Now intersect that with the extremity of temperatures at that time, and you can get an understanding of the marginal demand that you might see for non-renewable energy sources to plug that gap. And we were able to effectively demonstrate that by using these geospatial elements, these geospatial tools, you can predict what the change in prices of non-renewable energy, such as natural gas, might be.

Oscar Pulido: So what you’re saying, Mike, is that you had information about the weather that gave you insights on the demand for energy, whether that be renewable or non-renewable, and at the end of the day, that just allowed you to make a forward looking decision in portfolios that in the absence of that weather data, you wouldn’t have been able to make?

Mike Pensky: That’s exactly right, Oscar. And the important thing to also emphasize is that it’s not just having the data, but also relating that to the economics implications of what this means. You want to demonstrate that there is increased demand for energy at this point in time, but you also want to demonstrate that there is potentially a decline in marginal supply of renewable energy, which will then require an increased demand for that non-renewable energy source. And that’s really what we can trade in portfolios.

Oscar Pulido: You know most people get up in the morning and they look at the weather and influence is what they’re going to wear. Is it too hot? Is it too cold? And maybe you guys do that too, but you’ve also taken this a step further to think about what you’re going to do from an investment perspective. Weather’s an important component of this, but Josh what else does geospatial data do? Because I get a sense that there’s more that it can do than just weather-related insights.

Josh Kazdin: Absolutely, Oscar. Once you start looking for geospatial data, you’ll see it everywhere. The question, as Mike was alluding to before, is not just what data you want to look at, but ultimately, what economically sensible questions do you want to answer? Most recently, there’s been a lot of turbulence in the US banking sector centered around Silicon Valley Bank (OTC:SIVBQ). One of the ways that we took geospatial approaches to this data was that we looked to see which banks were also exposed to the Bay Area, both in terms of where their physical locations were, but also importantly, the location of where all their deposits were, which we get, data from the FDIC on. This helped us better understand the spillover impacts of the most recent banking turmoil in other parts of our portfolio.

Mike Pensky: Another exciting project that we’ve just completed looks at trying to understand the evolution of portfolios from the lens of US cities. We often talk about trading country exposures in portfolios but one thing that we found quite exciting is that there’s actually a lot of dispersion in economic activity even within, let’s say, the United States. An example would be, post COVID, there’s been a lot of migration within the US, particularly as remote work has become more popular; that actually has a lot of important spillover effects.

For example, as more people, let’s say, move into a region, economic activity might accelerate, real estate in that market might accelerate relative to another region where maybe that is not happening. And what ends up happening is companies that are in those locations will actually benefit from that increased demand and, as a result, you can actually position the portfolio in response to shifts and economic activity, not just at the global level, but even in very small regions. And this all takes very specific and precise measurements of geospatial economic activity that we can trade within the United States.

Oscar Pulido: I’m remembering an example from a while back. You’re probably going to tell me that we’ve moved on from this a long time ago and it’s so much more robust, the satellite images of parking lots of a Walmart and the images would tell you whether there’s high economic activity or not. And I think that’s an example of geospatial. But you might tell me that we’ve moved on past that already.

Mike Pensky: I think you’re right. When most people think about geospatial, they think of those images of cars in parking lots next to retail locations. But we have moved much beyond that. Hopefully the examples that we’ve given kind of demonstrate the breadth of the amount of data that we can process and the broad applicability of this. It’s not just about retail, it’s actually very broad. Where we can trade equities, country exposures, rates, currencies, it has very important meaningful implications that we can map to asset classes.

Josh Kazdin: In all honesty, the possibilities of this type of data are boundless. Some of the biggest questions that we have today in the market are geospatial in nature. What does the world look like after globalization as supply chains, trade, start to move more into different regions? What do we think about how artificial intelligence will ultimately be changing production? And are we supposed to be looking at consumption physically as people are going to a mall or online? All these different questions have ultimately a geospatial component to them. And to us, geospatial data is the alpha that’s ultimately hiding in plain sight.

The ability to take anything from the physical world and map it into your portfolio, discover some economically sensible relationships and then position your portfolio to take advantage of them is a huge opportunity for our clients. It’s like the number one rule in real estate, sometimes it’s ultimately just about location, location, location.

Oscar Pulido: The statement you made around alpha hiding in plain sight resonates because what you’re saying is the information’s out there, there are insights to be derived about trends in the economy, trends in markets, but you need, it sounds like, computing power. And there’s the two of you, but presumably there’s a big team behind this that is helping you process, analyze the insights, but that alpha hiding in plain sight seems to best encapsulate the fact that the information’s out there, it’s just a matter of having the right resources to be able to derive it.

Josh Kazdin: A hundred percent. And in all honesty, this entire effort wouldn’t exist but for a huge team of dedicated, talented, intelligent collaborators. These are engineers, researchers, portfolio managers, all unified by a passion to try to understand what’s happening in the physical world so that we can better do financial research using geospatial technology, and help our clients maneuver their portfolios to take advantage of what’s going on.

Mike Pensky: And then I’ll say I think we are still in the early stages here. One way I sometimes think about this is natural language processing wasn’t really a big part of the investment landscape; now it’s absolutely everywhere. We think it’ll take time, but we think that this geospatial idea, these concepts, the data, it’ll become much more important in portfolios over time, particularly as the tools are built out, and we’re very excited to be a part of it.

Oscar Pulido: Mike, you talked about natural language processing has made a lot of advancements in how we use it. Think ahead the next 10, 20 years for geospatial. What do you imagine it’s going to look like and how you’re going to utilize it?

Mike Pensky: As I mentioned, Oscar, we’re still at the early stages and I think we’re going to take incremental steps towards a final vision, to be able to evolve portfolios really as the world turns. In the interim, what are things that we’re trying to tackle? Interacting different data sets with each other, trying to use many things happening to predict what will happen then after that point. But ultimately the thing that we would love to happen is the world turns, a bunch of stuff happens on the surface of the earth, and we immediately know how to reposition our portfolios in response to that. It’ll become much more automatic where we’ll be able to interpret these events and actually be able to reposition portfolios.

Josh Kazdin: If you think about today, any news article that you read is going to have a mention of a city or where the reporter is talking from. If you look on social media, you’ll oftentimes find a geospatial tagged piece of information about what somebody is talking about, where they’re talking about it from, or if they’re live streaming from a concert or from an experience that they are having.

If you look at where ships are positioning across the globe and where tradable goods are moving, each one of these have geospatial data within them. And so, we want to be able to use all of that information in near real time to uncover actionable insights that we can use to better invest for our clients.

Oscar Pulido: Outperforming the market is hard work. But just listening to the two of you, it sounds like you’re doing some pioneering work that hopefully increases the odds of that going forward. So, Josh and Mike, thanks so much for joining us today on The Bid.

Mike Pensky: Really appreciate it.

Josh Kazdin: Thank you very much.

Oscar Pulido: Thanks for listening to this episode of The Bid.

This post originally appeared on the iShares Market Insights.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here