Last week, the Fed effectively announced there would be no rate hike at the June 14th FOMC meeting, but there might be a hike at the July 26th meeting. I think the information we have to date strongly suggests that the Fed is done—no more hikes. The only question now is when they start to cut and by how much. Currently, the bond market is priced to a 50% chance of a 0.25% hike at the late July meeting, and at least a 1% cut by year end, with the peak funds rate coming in late summer. I think there’s a decent chance we will see short-term rates end up lower than current expectations.

My reason for being bullish on bonds (i.e., expecting lower interest rates) is based on my observation that inflation will continue to decline. I’m optimistic the economy will avoid a recession because I see low and falling swap and credit spreads, which in turn are indicative of a healthy outlook for the economy and corporate profits.

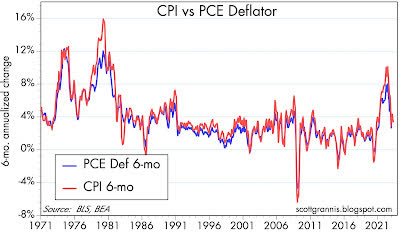

Chart #1

Year over year measures of inflation fail to pick up turning points until after the fact. That’s why I prefer to use a 6-mo. annualized measure of inflation, which I’ve used in Chart #1. Both the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflator and the CPI have fallen to below 4% by this measure (CPI 3.3%, PCE deflator 3.5%), and are within striking distance of the Fed’s 2% target.

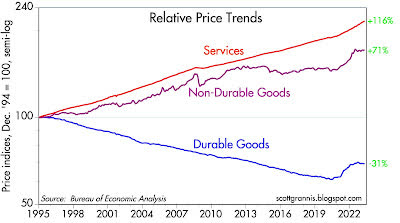

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows the relative behavior of the three main components of the PCE deflator. The striking news here is that durable and non-durable goods prices have not changed at all since last June! The only prices that have been rising in the past 10 months are services prices; and shelter prices (rents and housing prices) make up a large portion of services prices.

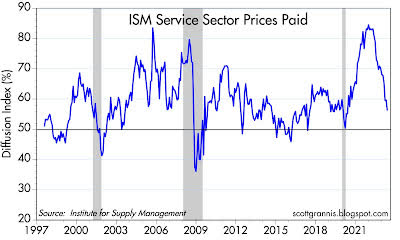

Chart #3

As for the rest of the service sector, the May ISM survey (Chart #3) shows that only a small majority of service sector firms report paying higher prices. That’s lower than the historical average for this survey, which is 60%. That’s relatively recent data which confirms that inflation pressures continue to fall for this very important segment of the economy.

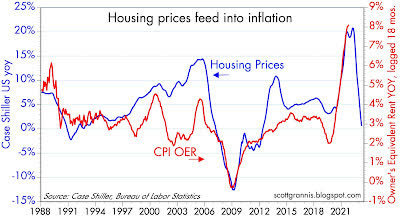

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows how changes in housing prices take about 18 months to show up in the CPI, through what is called Owner’s Equivalent Rent, which in turn comprises about one-third of the CPI. Since housing prices have how been falling for the past 18 months, the OER component of the CPI will become negative in coming months, thus subtracting a major portion of upward inflation pressure in the CPI.

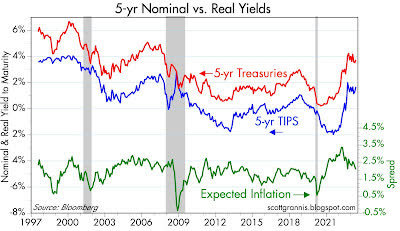

Chart #5

Not surprisingly, the bond market has figured this out. The green line is the market’s expectation for what the CPI will average over the next 5 years: 2.15%. If you convert this to the PCE deflator, that’s roughly equivalent to a forecast that the PCE deflator will average 1.7% or so over the next 5 years—and that’s less than the Fed’s target of 2%. Does the Fed pay any attention to the bond market? I sure wish they would.

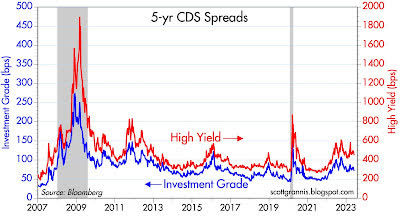

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows Credit Default Swap spreads, which are a highly liquid proxy for corporate credit spreads, which in turn are indicators of the market’s confidence in the outlook for corporate profits—and by extension for the outlook for the health of the economy. CDS spreads are relatively low and have been falling since the Silicon Valley Bank fiasco. This is very comforting.

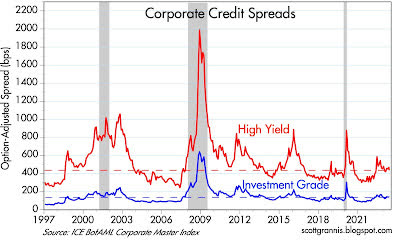

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows a broader and somewhat less liquid measure of corporate bond spreads. By this measure too, spreads are relatively low and have been falling in recent months.

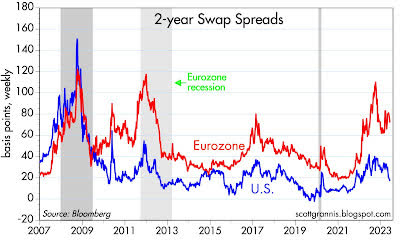

Chart #8

Chart #8 shows 2-year swap spreads, which are excellent and very liquid indicators of market liquidity and the outlook for the economy. Here too we see that conditions in the US have been improving of late and are generally quite healthy. Even conditions in Europe have improved of late. At current levels, 2-yr swaps in the US are in the lower portion of what a “normal” range would be. I think this is highly important, since it shows that the Fed’s tightening actions have not resulted in a loss of liquidity in the bond market, and that in turn is essential to healthy, functioning markets. The Fed has raised rates by enough to balance the demand for money with the supply of money, and that is all it takes to bring inflation down. There is no need for the Fed to intentionally weaken the economy in order to fight inflation. (Higher rates make you more inclined to hold on to your cash, since it can be invested at a decent rate, contrary to the conditions that prevailed early last year, when short-term interest rates were close to zero.)

All things considered, the economy should avoid a recession, inflation should continue to decline, and sooner or later the Fed will be lowering short-term interest rates.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here