American Airlines Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner on approach to LAX

The American Airlines (NASDAQ:AAL) of today is the result of several mergers, the most recent of which was with US Airways in 2013, concluding the reorganization of AMR Corporation, American’s former parent, under Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Through that merger, American gained a powerful domestic hub network as well as a number of distinctives including the largest workforce at any U.S. airline. As the last of the four U.S. airline megamergers, American and USAirways were the only two continental U.S. long-haul legacy carriers remaining after the Delta (DAL), United (UAL), and Southwest (LUV) mergers. American’s hubs range from New York City to Florida on the East Coast with Charlotte serving as the belt buckle, key central U.S. hubs at Chicago and Dallas/Ft. Worth as well as hubs in the southwest U.S. in both Phoenix and Los Angeles. Its northeast U.S. hubs include both New York’s LaGuardia and JFK airports, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. National airport, creating one of the most dense hub overlaps in modern U.S. history and one which American has not yet managed to harmonize. Unlike Delta and United which closed one or more hubs as part of its network restructuring post-merger, American has not closed any of its hubs but instead has tried to balance the internal competition between its northeast hubs since many connecting passengers can be carried over any one of those hubs, making it much more difficult for American to generate the mass necessary to maximize profitability.

New York’s JFK and LaGuardia, as well as Washington National airports are all slot-controlled by the Federal Aviation Administration, serving both as a cap on the number of flights but also to limit competition. American is the largest slot holder at Washington National (DCA) with approximately 60% of the slots while it is the second largest carrier at LaGuardia (LGA) with approximately 25% of the airport’s slots behind Delta and the third largest carrier at JFK airport behind Delta and JetBlue (JBLU). Even before Covid, the Dept. of Transportation notified American that it was not satisfying slot usage requirements at LGA and JFK airports and that the company was at risk of losing some of its slots if it did not come up with a plan to increase usage. United Airlines failed to use its slots to federal requirements at Newark Airport – where it controlled over 70% of the slots – and the FAA removed the highest level of slot controls in 2016, resulting in new competition and increased delays as the artificial limits of slot controls pushed the number of flights at the airport above levels that the airport could efficiently handle.

American’s failure to use its slots at JFK and LGA airports was a result of its declining competitiveness at some of the largest airports on both coasts, a phenomenon which itself was the result of American’s industry-high unit costs during the period from 2005 to 2010 when American was the only remaining large legacy carrier that had not reorganized under chapter 11. JetBlue grew rapidly during the first decade of this century including at its JFK home while Delta, during its reorganization, committed to build major hubs at both LGA and JFK airports where it currently operates over 500 flights/day, which combined with its presence at Newark, makes Delta the largest airline in New York City. JetBlue gained a relative handful of slots at LGA during its 20-year life but its roughly 175 flights/day is enough to allow it to match Delta’s domestic size at JFK airport with the remainder of Delta’s slots being used for long-haul international flights. Unable to compete with the larger United at Newark and Delta at LGA and JFK as well as JetBlue at JFK, American began looking for options.

Northeast Alliance

American previously had a limited codeshare agreement with JetBlue to help feed passengers onto American’s long-haul international flights from JFK and the option its strategists favored as it developed a strategy to comply with slot usage requirements built on its cooperative history with JBLU. Of course, Covid threw a major monkey wrench into airline plans to utilize their capacity and American and JetBlue developed what would become the Northeast Alliance – an antitrust-immunized limited joint venture that involved the ability for the two airlines to swap slots at JFK and LGA airports, to jointly plan capacity in markets to/from NYC and Boston, which was also included in the agreement, and share revenue. The U.S. DOT approved the plan and AAL and JBLU began to increase their marketing cooperation while AAL transferred some of its LGA slots that were being flown by regional jets to JBLU while AAL gained slots during peak international time slots at JFK with JBLU taking over AAL slots at off-peak periods for international flights.

American-JetBlue tails (AA.com)

The ink was barely dry on the agreement when the U.S. Dept. of Justice filed suit against the arrangement. Although the DOJ had failed to win a number of key merger cases, it seemed confident as it presented its case to a federal judge in Boston last fall that the AAL-JBLU agreement contained troublesome antitrust characteristics. The DOJ noted that no other two U.S. airlines had ever been allowed to cooperate on the same basis as the Northeast Agreement. The judge ruled on May 19 that the Northeast Alliance had to be disbanded within 30 days and the airlines had to present a plan within three weeks as to how they will accomplish that requirement.

The judge noted that, besides allowing AAL and JBLU to jointly limit capacity in a number of markets that one or both operated pre-NEA agreement, the two carriers had limited capacity and removed one of the two carriers in a number of markets. Even though the two carriers noted that they started a number of new routes (some of which were actually routes which American had flown much earlier but was not flying at the time the NEA was implemented), that did not legitimize reduction of competitiveness in a number of larger markets.

Faced with a growing shortage of regional jet pilots and increasing labor costs, American transferred a number of its LGA slots to JBLU where the low-cost carrier used larger aircraft which should have resulted in improved economics. At JFK, American added several new long-haul international routes including Delhi, Doha, and Tel Aviv, and depended on JBLU to help connect passengers to those flights. As part of the testimony in the trial, American revealed that several of its long-haul international routes did not do as well as expected and JBLU was required to pay American $200 million as part of the revenue sharing agreement, an amount that was dramatically reduced.

The judge also noted that American and JetBlue both shifted resources from other parts of their networks in order to build capacity in New York City and Boston and thus effectively colluded to reduce capacity in other markets. Because of the number of its hubs in the northeast U.S., American shifted much of its long-haul international focus from Philadelphia which had been its largest long-haul international hub in the northeast to JFK airport. With the prospect of unwinding the Northeast Alliance and a list of unsuccessful international routes, American will spend the rest of the summer thinking through its long-haul international route system for 2024 and beyond. Unlike Delta and United which have large numbers of widebody aircraft due for delivery in the near term, American’s widebody (long-haul, dual aisle) order book of Boeing 787 aircraft is only large enough to replace its 777-200ER fleet – but AAL has not indicated it intends to replace that fleet as it waits for enhanced versions of Boeing’s new generation widebody. AAL has recognized that it does not compete as well in many of the markets outside of the UK and S. America that Delta and United serve and so previously decided to reduce its presence in continental Europe and Asia. Ending the NEA will present AAL with a significant challenge in trying to further refine its role as a global carrier, especially relative to Delta and United which are both aggressively seizing opportunities to grow their international networks.

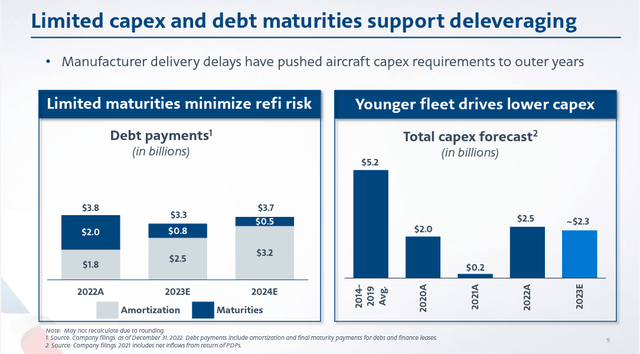

AAL capex and deleveraging (AA.com)

West Coast Presence

As part of his judgment regarding the Northeast Alliance, Judge Sorokin noted that AAL and JBLU could have implemented an agreement similar to what AAL has with Alaska Airlines (ALK). Unlike Delta and United which each have multiple transpacific gateways on the west coast, American only has Los Angeles (LAX), which it tried to build into a significant presence pre-Covid, resulting in a number of poor-performing routes according to AAL execs. The company pulled down a number of transpacific and domestic routes, allowing Delta to become the largest carrier at LAX, displacing American from that role which AAL had held for years. In order to gain the mass it needed to compete with DAL and UAL, AAL developed a simple codeshare agreement without joint planning or revenue sharing that covered most of the west coast including ALK’s primary hub at Seattle, where Delta also has a transpacific hub.

Notably, the American-Alaska partnership became a model that Judge Sorokin said AAL-JBLU should consider to maintain a partnership in the Northeast. Indeed, ALK has joined the oneworld global airline alliance even though it has codeshare and loyalty program partnerships with most foreign airlines other than Delta that serve Seattle. While LAX is not well suited geographically as a transpacific hub, it is a massive local market, and because LAX is the dominant airport in Southern California, LAX is the most valuable local air market at a single airport. As part of the AAL-ALK partnership, AAL withdrew from a number of north-south markets up and down the west coast, leaving ALK to serve those markets but the two airlines did this without violating any antitrust laws and while still leaving a more robust competitive market, in part because no airports on the west coast have federal slot controls.

As part of the AAL-ALK partnership, American said it would develop Seattle as a transpacific gateway, creating a west coast international hub that looked like Delta; AAL stated that it intended to start service to Bangalore, India, a major tech destination that was dependent on large companies that are based in Seattle and the San Francisco Bay area where United operates its largest transpacific hub at San Francisco. However, the tech industry has been one of the slowest to return to significant international business travel. A route from Seattle to Bangalore would have pushed the limits of the Boeing 787-9, the longest-range aircraft in American’s fleet. Embargoes of Russian airspace sealed the fate of a route to Bangalore. Two of the routes which AAL suspended from LAX were to Shanghai and Beijing; potential new AAL routes to China from Seattle have been dashed by strict capacity limits by the Chinese government on the number of flights that U.S. and Chinese carriers could operate. One of the few viable long-haul international routes that American could operate was to London Heathrow where American and British Airways operate a major joint venture hub. AAL operated a Seattle to London route alongside British Airways and a number of other carriers but recently filed schedules indicating that the route would be suspended in the fall and would not return.

The AAL-ALK route, while a model for the type of partnership that American could have with another domestic airline, has not improved AAL’s position as a distant third-place airline compared to the global networks of Delta and United. Further uncertainty about AAL’s northeast U.S. strategy creates even more uncertainty about how AAL will rebuild a profitable and competitive route system other than to its major joint venture partner hubs.

Very Strong Southern Hubs

Well before the Covid pandemic, American identified that its hubs at Washington National, Charlotte, and Dallas/Ft. Worth were its highest margin hubs and it began to shift an increasing amount of resources to those three hubs. Charlotte, North Carolina doesn’t even rank in the top 20 largest local travel markets, but USAirways and now American have built the airport into the third largest hub in the U.S., tapping into the massive eastern U.S. traffic flows that have helped make Delta’s hub at Atlanta the world’s largest. AAL continues to grow its Charlotte hub, opening new transatlantic and domestic routes even as the Southeast U.S. sees a growth boom in the post covid world.

Dallas/Ft. Worth airport is one of the Covid era’s demographic winners as Texas in general and N. Texas specifically has seen strong growth in the remote/work-from-home environment and as many people in the country move to lower tax states and high-growth cities. DFW airport is ideally located in the middle of the southern tier of the U.S. and American operates the world’s second-largest hub there, behind Delta’s Atlanta hub. As American has struggled to find its place in major Northeast and west coast markets, it has been able to successfully operate flights to Asia and Europe as well as American’s core strength in Latin America even though Texas is a relatively poor location for a primary long-haul airline hub. AAL and the DFW airport recently announced the development of a new terminal at DFW airport which should allow American to continue to grow.

N. Texas aviation competitively is one of the most interesting markets. When DFW airport opened, the intent by local leaders was to replace Dallas Love Field airport. Southwest had other ideas, however, and succeeded in a lengthy court battle to remain at the close-in airport, establishing LUV’s business model of serving smaller urban airports. A series of legal maneuvers have kept AAL and LUV out of each other’s primary airports in N. Texas but those requirements end in a couple of years. Although AAL was forced to divest its two gates at Love Field, that requirement will also end within a couple of years. AAL leased its two Love Field gates to Alaska Airlines which underutilized its gates, allowing Delta to successfully fight to gain one of the two gates as its own, leaving American with a maximum of one gate at Love Field. Southwest will be free to expand to other airports in N. Texas including DFW airport. Over the past five years, LUV has successfully entered major legacy hub airports such as Houston’s international airport and Chicago O’Hare and is likely to do the same at DFW. While N. Texas remains a bright and financially strong spot in AAL’s network, the competitive environment will become more intense in the coming years.

American’s hub at Miami has long been in an advantageous position both as the primary airport to Latin America and also because American is the only U.S. legacy carrier that operates a hub at that airport. The northern tier of Latin America remained open to U.S. tourists during the Covid era while the Southern cone of S. America is resuming its position in the post-Covid travel environment even as American has long been more dominant in that region than either Delta or United is in any other global region. AAL’s Miami hub has faced intense competition from nearby Ft. Lauderdale, which has become a low-cost carrier gateway to Latin America with major “hub” operations by JBLU and Spirit (SAVE). While the Dept. of Justice is opposing that merger because of the significant size and overlap of those two carriers at Ft. Lauderdale, many analysts believe that the chances for approval of that merger are improving. Should JBLU and SAVE be allowed to merge, it is certain that the competitive environment in South Florida will become less intense, leading to a stronger pricing environment which would benefit AAL and its Miami hub.

A Bright Light at Tokyo?

While there appears more uncertainty around American’s international route system than the company has seen in a number of years, one bright spot might be its flights to Tokyo’s Haneda airport. For decades, all flights between the United States and Tokyo were from Narita airport which is more distant from downtown Tokyo, while close-in Haneda airport was largely for domestic and intra-Asia flights. The Japanese government decided a decade ago that Haneda, one of the busiest airports in the world, would grow and become the primary airport for long-haul Tokyo international flights while smaller and more distant Narita airport would become a low-cost carrier and essentially an overflow international airport. The U.S. and Japan renegotiated its air services agreement and opened Haneda airport to transpacific flights with the first flights arriving and departing late at night. In the most recent revision of access to Haneda, U.S. airlines were granted nearly 20 flights to/from Haneda with Japanese airlines gaining the same number. American operates its flights to/from Japan in an antitrust-immunized joint venture with Japan Airlines while United has the same type of cooperation with All Nippon Airways. American currently operates the least number of flights of the big-3 global carriers with two flights from Los Angeles to Haneda and one from DFW. The most recent routes were activated in March 2020, just weeks after the Covid pandemic began.

Delta was awarded the largest number of flights from the U.S. to Haneda, but has never operated all seven of the flights it was awarded; governments around the world granted exemptions to usage requirements because of the pandemic. Japan recently removed all Covid travel restrictions and travel has begun to rebound but has been slow. Delta recently petitioned the U.S. Dept. of Transportation for permission to move two of its seven routes to different gateways, noting that although the U.S. has an Open Skies agreement with Japan which normally does not cap the number of flights an airline can operate or require government approval for where those flights have to operate, the U.S. air services agreement with Japan specifically carves out those requirements for Haneda airport. Because of their joint ventures and the way the Japanese government awarded slots to its airlines, American and United effectively have the ability through their JAL and ANA to move their Haneda flights between U.S. gateways, something U.S. airlines cannot do. American and Hawaiian supported Delta’s request with the DOT while United has vigorously opposed it; United and ANA are the largest operator of flights between the U.S. and Japan under their joint venture. While Delta and United have exchanged sharply worded filings with the DOT, there appears to be sufficient desire among three of the four U.S. airlines for the DOT to grant Delta’s request which would allow all U.S. airlines the ability to move up to two of their Haneda flights. While none of American, Delta or Hawaiian have indicated what they would do with their two Haneda flights if they were allowed to move them, American pulled out of the Chicago to Asia market several years ago. American has long said that it would like to add Miami to Tokyo service, a route which is not operated by any airline. American’s Philadelphia and Charlotte hubs have never had Tokyo service. And AAL could choose to add a second daily Haneda flight from DFW where it is certain to get its best transpacific margins. American asked for a flight, but it was not approved for a flight from Las Vegas to Tokyo as part of its latest Haneda application process almost five years ago. Although American has a small presence in Asia, the ability to move one of its Haneda flights could accelerate its transpacific margin rebuilding process.

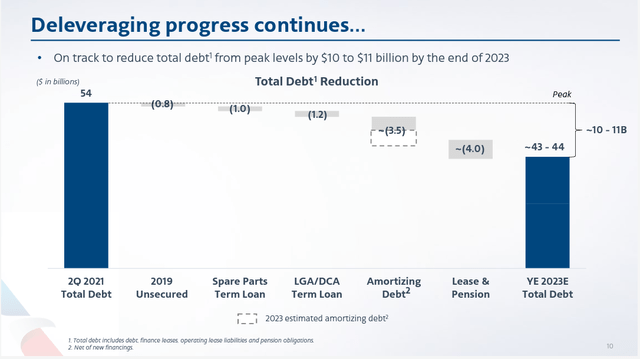

AAL deleveraging (AA.com)

Laser-Focused Financial Rebuilding

AAL has long been considered one of the riskiest U.S. airline investments, a result of its industry-leading debt levels and its low profit margins that persisted for years. Robert Isom took over as CEO just over a year ago and seems to be charting a much more financially prudent path for AAL. He has sharpened American’s focus on eliminating loss-making routes and focusing on American’s profitable network strengths. He also has committed to slowing AAL’s capex after almost ten years of industry-leading aircraft spending. American has touted that it has the youngest fleet among the largest U.S. airlines – and that now gives them the ability to dramatically slow their capex as they pay down debt using their cash flow which is at decades-high levels. In fact, AAL’s aircraft capex on its books is less than one-fourth of what UAL is committed to spend as part of its fleet renewal; UAL will likely take AAL’s place as the most indebted U.S. airline. Given the strong demand environment and guidance that is closer to being in line with DAL and UAL than AAL has seen in nearly two decades, AAL is likely to at least meet its debt reduction targets which should dramatically improve investor sentiment.

New Labor Agreements and Costs

AAL’s near-term profits will take a hit as it brings its labor groups up to what are now industry standard levels. In December 2022, Delta came to an agreement with its pilots for a massive pay raise and a new four-year contract that includes retroactive pay for parts of the past four years during which its pilot contract was amendable; airline labor contracts do not expire and labor frequently continues to work past the amendable date with retroactive pay common. Airline pilots are in a particularly strong position right now because of the shortage of pilots coming up through the ranks of regional carriers. Delta and American undoubtedly both see the necessity to raise pay in order to ensure a supply of new pilots. The Delta pilot contract – which has since been ratified – cost the company more than $750 million in cash as part of the retroactive salary adjustments. It is likely that American will face a similar bill. American has the oldest pilot workforce of the big-4 so it needs a supply of new pilots but also could offset part of the cost of the new contract as more senior pilots retire with the cash and pay raises that will come with the new contract. United and Southwest are both still negotiating with their pilots.

American’s flight attendant contract is also currently open. Delta also raised the pay of its non-union flight attendants and implemented pay during boarding; U.S. airline flight attendants historically have been paid only for flight hours and not during boarding and deplaning. Nearly all unionized flight attendants, including those at American, are including requests for boarding pay in their proposals to their airlines. It is very possible that American’s labor costs could increase by more than $2.5 billion per year as part of updated labor contracts. It is noteworthy that American was the second of the big-4 to come to an agreement with its pilots given the perception that it is less financially stable than Southwest or United. Management’s willingness to come to an agreement with its pilots, which will likely lead to an agreement with its pilots, indicates that American believes it can absorb the higher labor costs even as it improves its balance sheet and its margins.

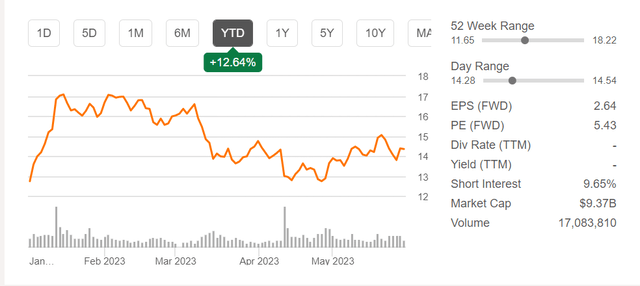

AAL chart 29 May 2023 (Seeking Alpha)

As the Memorial Day weekend comes to an end and the summer travel season kicks off in earnest, airlines are expected to record very strong revenues. They have spent over a year improving their staffing levels and ensuring workers are prepared for the levels of demand that are expected. While American finds that it has to once again rethink its network strategies, especially around its northeast and international networks, it appears to have a profitable strategy driven by its southern U.S hubs.

AAL ratings summary 29 May 2023 (Seeking Alpha)

Given AAL’s expected cash payments for retroactive pay for its pilots and possibly for its flight attendants, I have to rank AAL as a hold in the near term but remain optimistic that the company is returning to being a valid financial competitor to Delta, Southwest, and United in the U.S. airline industry.

Read the full article here