Always look on the bright side of life, Monty Python once sang, and that’s a message the stock market seems to be embracing.

Of course, the pessimists among us—including yours truly—have been focused on what could go wrong. The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by five percentage points over the past 14 months, and may not be done yet, if central bank governors like Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan and St. Louis Fed President James Bullard are to be believed.

The banking system, though stabilizing, is still under pressure, with credit conditions tightening. Leading indicators have fallen for 13 consecutive months, the longest since the 24-week streak ended in March 2009, pointing to a possible recession in the months ahead.

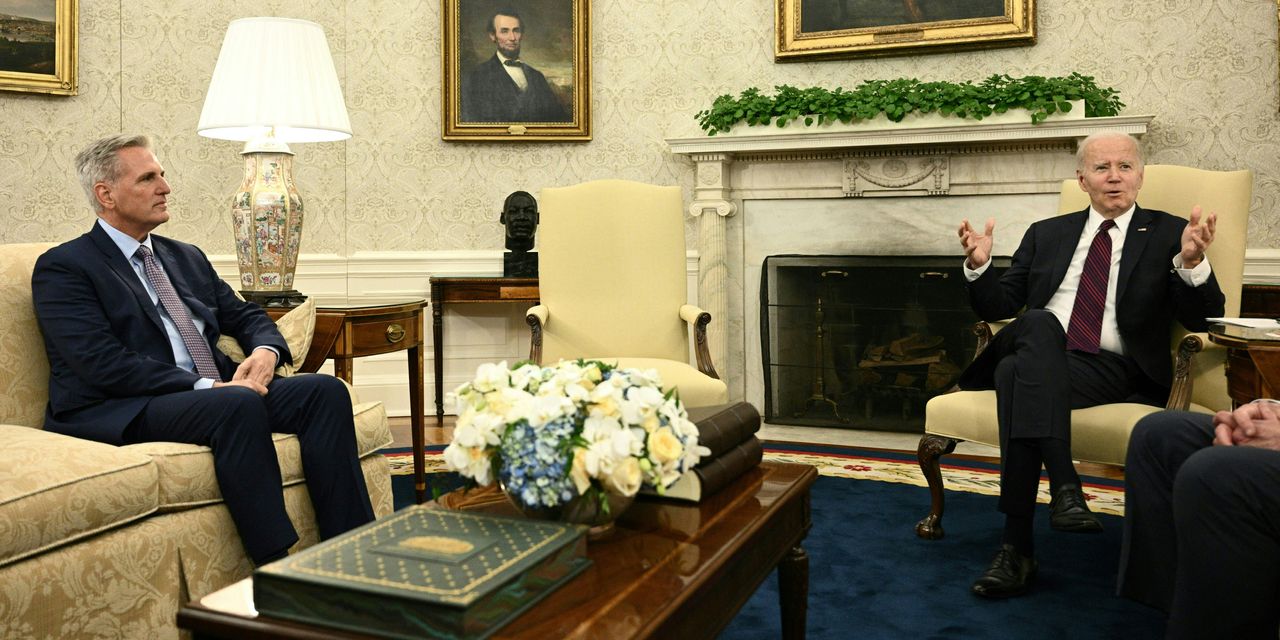

And the debt ceiling is still unresolved, leading none other than Bridgewater Associates’ Ray Dalio to warn that it would lead to a “disastrous financial collapse.”

The stock market doesn’t seem to care. The

S&P 500

rose 1.7% this past week, and even on Friday—when it was hit by the double whammy of Republicans walking out of debt-ceiling talks and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen saying more bank mergers would likely occur, suggesting continued problems in the financial system—the index dropped only 0.1%, meeting the news with the equivalent of a shrug.

In fact, the market appeared to start pricing in a debt-ceiling deal, which few would point to as the likeliest outcome, while focusing on the fact that inflation is falling, not that it is still higher than the Fed would like. One might say the market truly is acting like the most annoyingly optimistic person we know right now.

But there’s no arguing with it. We mortals might worry about the debt ceiling and what it will mean for the cash we have in money-market funds and the value of our stock portfolio. We might worry about egg prices. We might worry about recommending that investors buy stocks only to see them get obliterated. The stock market, though, doesn’t have to think about those things. It only goes up or down.

It’s hard for the market to truly sell off if no one actually owns stock. UBS analyst Sean Simonds notes that the positioning in U.S. stocks in funds of all types is two standard deviations below average levels, according to the bank’s data, with balanced and long/short fund allocations notably pessimistic. The funds’ cash levels are high, too. That doesn’t make Simonds any more optimistic about the stock market—there’s still a “heightened risk of near-term selloff,” he says.

Yet it does raise the question of who will be doing the selling, particularly after the treacherous path stocks took over the past 16 months. First, it was the bear market that caused the S&P 500 to drop 25% from peak to trough, while pulverizing the biggest, most popular stocks, including

Apple

(ticker: AAPL),

Microsoft

(MSFT), and

Amazon.com

(AMZN).

More recently, it’s been the pain of watching what worked in 2022 fall apart, while Big Tech—and Big Tech alone—lifted the S&P 500 out of its deepest lows, leaving investors wondering if buying now means they will have bought the top. But if sidelined investors get off the fence and decide to buy, that alone could push stocks higher.

In the meantime, it’s fair to ask what the market does care about. It seems to be enamored with stocks that benefit from the artificial-intelligence trend, without which the S&P 500, through May 12, would have dropped 2% instead of gaining 8%, according to Société Générale data. And it’s having a love affair with its biggest stocks—

Nvidia

(NVDA),

Alphabet

(GOOGL), and the aforementioned Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon—which account for more than a fifth of the S&P 500 and have also benefited from the AI theme.

For many, the market’s narrow breadth is just one more reason to be down on the S&P 500. But that’s not always the case. Those five stocks now account for more than a fifth of the S&P 500, notes Brian Belski, chief Investment strategist at BMO Capital Markets, up from 17%, and previous peaks in concentration have resulted in an average gain of 4.1% for the index over the following six months.

What’s more, the gains are led not by the big guys, but by the smaller stocks in the index, with the S&P Equal Weight Index averaging a gain of 13.9%. “Top-heavy market cap concentration in [the] S&P 500 is not necessarily detrimental for performance,” Belski writes.

We often forget that the market rarely breaks under the weight of negativity alone—and boy, are people negative. The University of Michigan Sentiment Survey remains well below its long-term average after hitting the lowest level in at least 40 years last June. Every time the index goes below 59 has been a good time to buy stocks if one has a two- to five-year outlook, according to Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research. “Sentiment, when it is this distressed, is always a contrary indicator,” he explains.

Unless we’re just whistling past the graveyard.

Write to Ben Levisohn at [email protected]

Read the full article here